Archaeologists have discovered solid genetic evidence linking western European Neanderthals with those who lived thousands of kilometers to the east in Siberia, casting new light on their long-distance migrations across Ice Age Eurasia. The discovery, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is centered on a small bone fragment that was excavated at the Starosele rock shelter on the Crimean Peninsula—a site associated with Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals but which had previously lacked any preserved DNA.

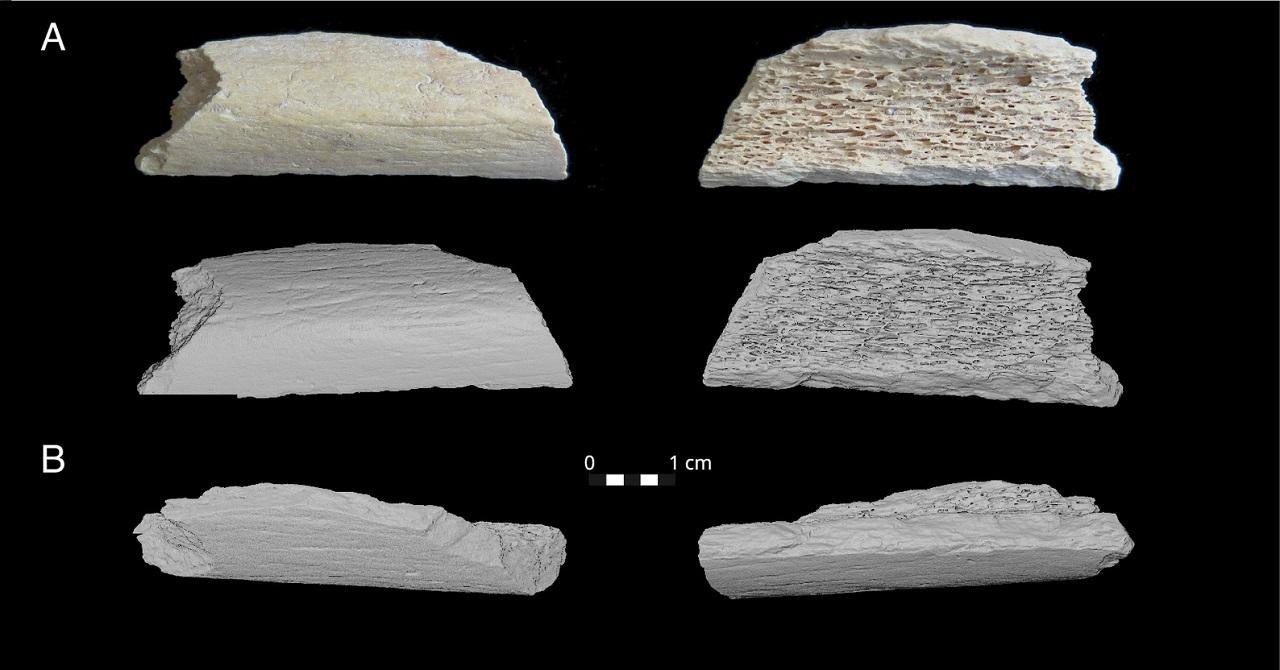

Of more than 150 bone fragments analyzed at Starosele, only one five-centimeter-long fragment revealed traces of Neanderthal DNA through collagen peptide mass fingerprinting, a method known as Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS). Most of the remaining fragments—some 93 percent of them—belonged to horses, and it seems that the Neanderthals who lived at the site were adept horse hunters and highly dependent on the animals as a source of food. Small amounts of wolf, bison, and rhinoceros bones were also identified.

Radiocarbon analysis confirmed that the Neanderthal bone was between 45,000 and 46,000 years old, placing it near the time Homo sapiens began expanding across Europe, while the Neanderthals were gradually disappearing. The researchers sequenced mitochondrial DNA, inherited maternally, and confirmed the bone’s Neanderthal origin. They named the individual “Star 1.” Genetically, Star 1 was also shown to be closely related to Neanderthals who lived thousands of kilometers to the east in Siberia’s Altai region, such as individuals from the Denisova Cave, Chagyrskaya, and Okladnikov sites.

This genetic link, spanning roughly 3,000 kilometers, provides strong evidence that Neanderthals were not limited to isolated European refuges but maintained population links across a vast Eurasian landscape. The recovered stone tools at Starosele, which represent the Micoquian lithic industry, mirror those from the Altai, providing additional support for the idea of cultural continuity between distant Neanderthal populations. These similarities point to direct migration or prolonged contact that allowed ideas and tool traditions to travel with individuals.

To understand how such migrations were possible, the team reconstructed paleoclimate conditions between Crimea and the Altai Mountains. Their habitat modeling identified a corridor at approximately 55°N latitude that would have supported migration during warmer periods between 120,000 and 100,000 years ago, and again roughly 60,000 years ago. Herds of large mammals such as horses and bison would have moved through this corridor during these favorable climatic windows and attracted Neanderthal hunters, allowing gradual population dispersal.

The find at Starosele completes an essential page in the broader story of Neanderthal migration and interaction with other ancient human groups. As these populations expanded across Eurasia, they would have encountered both Denisovans and Homo sapiens, leading to episodes of genetic exchange that are still detectable in human DNA today. The findings of the research demonstrate that Neanderthals were not static cave dwellers but rather mobile, adaptable, and capable of living in varied environments.

Although the Star 1 bone fragment is small and genetic coverage is incomplete, it provides the first direct genetic evidence of Neanderthals from the Crimean Peninsula and forms an important connection between Siberian and European populations. The results highlight how technical developments in biomolecular archaeology can recover information from the most fragmentary of remains and rewrite parts of human prehistory previously thought lost forever.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.