Archaeologists from the University of California at San Diego and the University of Haifa have discovered the oldest known Iron Age ship cargoes found in a known port city in Israel, yielding direct, rare evidence of maritime trade in the eastern Mediterranean. The discovery, published in Antiquity, redefines what was known about seaborne trade during the Iron Age and reveals how shifts in regional power influenced trade between Egypt, Phoenicia, and the southern Levant.

The finds were recovered at the Dor Lagoon—also known as Tantura Lagoon—on Israel’s Carmel Coast, which was home to the ancient port city of Dor. A research team led by Thomas E. Levy of UC San Diego and Assaf Yasur-Landau of the University of Haifa found three submerged cargo assemblages dating from the 11th to 6th centuries BCE. These results provide the earliest direct link between maritime activities and an Iron Age urban center in the region, bridging a gap previously known only through land-based evidence.

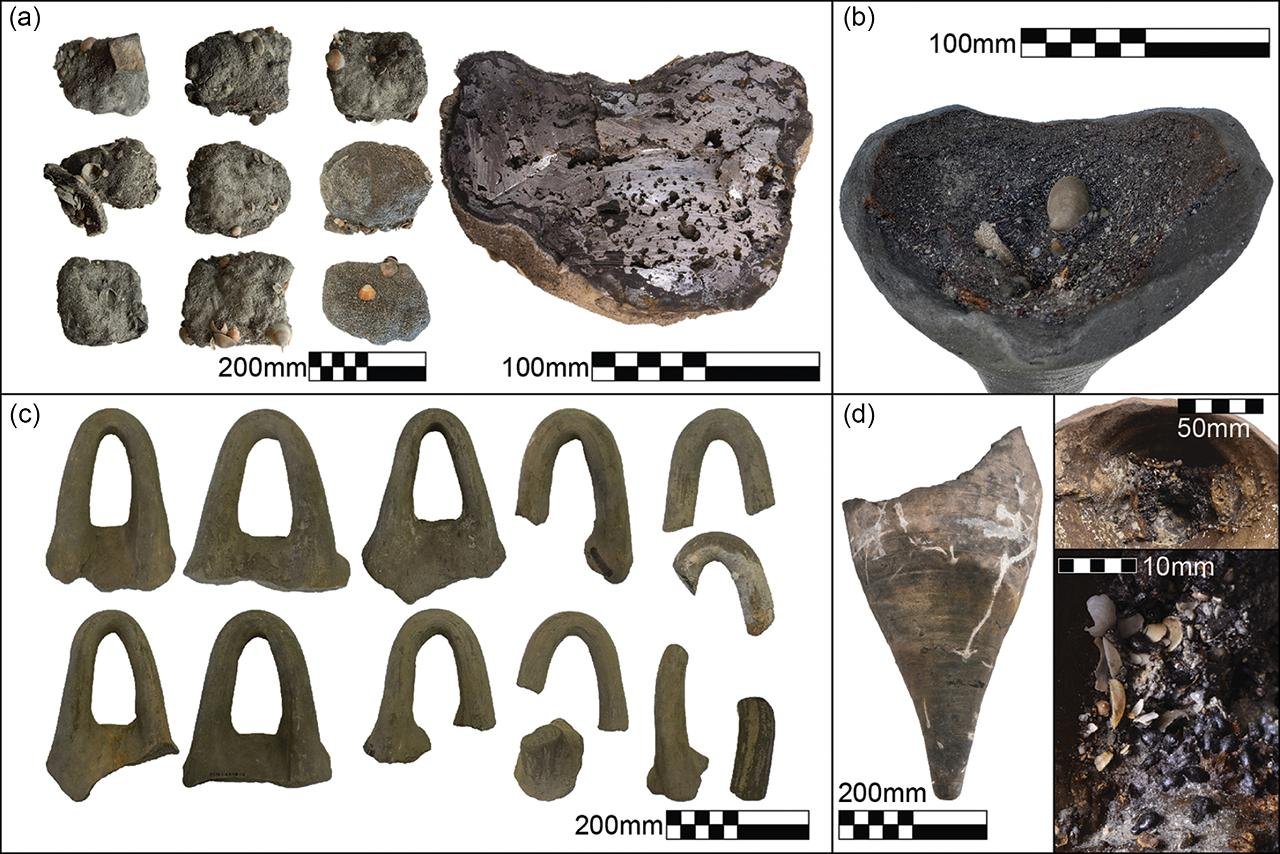

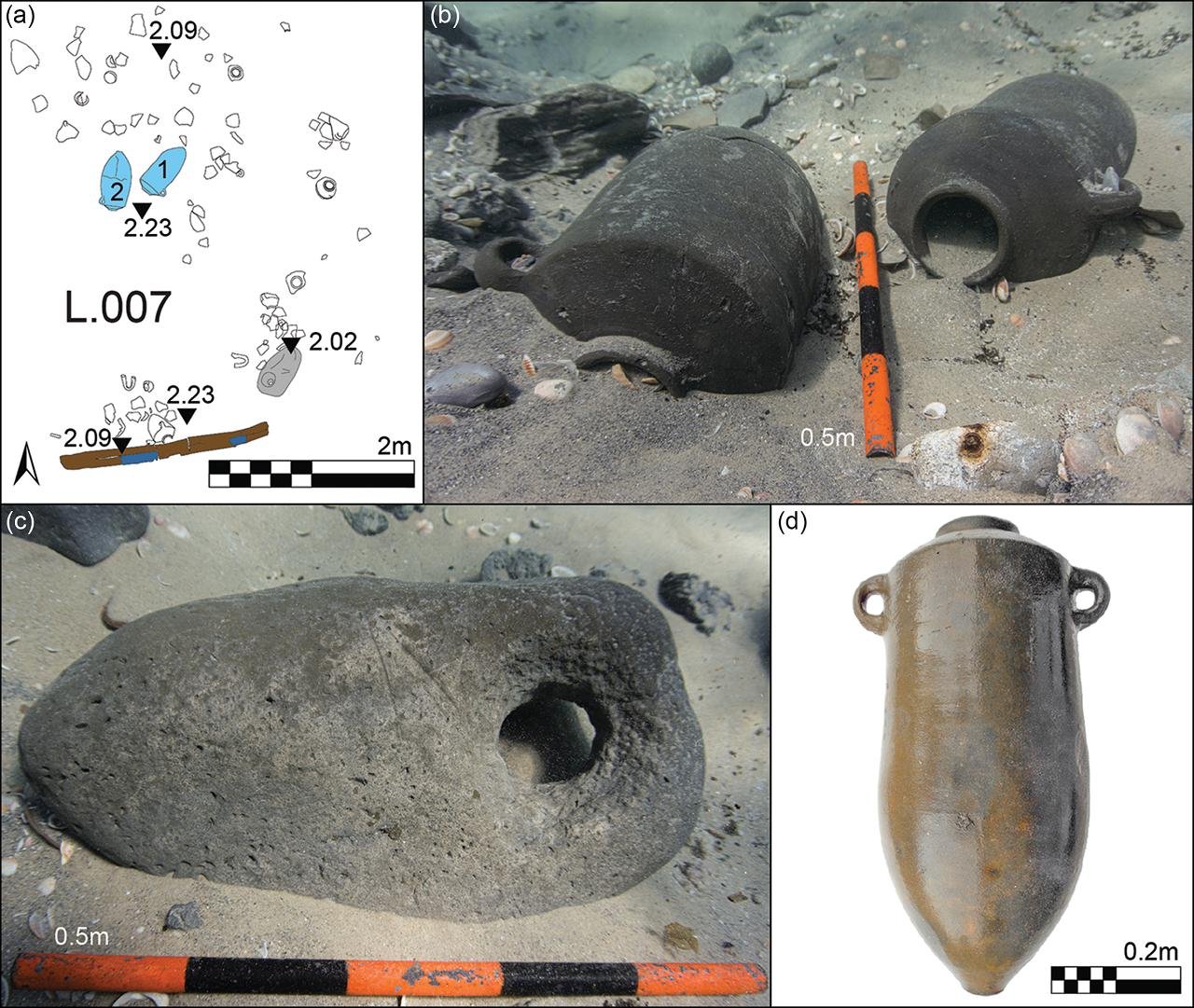

The first assemblage, Dor M, dates to the 11th century BCE. It includes storage jars and an anchor with Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, connecting Dor to Cyprus, Egypt, and the Phoenician coast. This phase is contemporary with the Egyptian Report of Wenamun, a literary text describing voyages to Dor and nearby ports, attesting to the city’s place in early Mediterranean networks of trade following the Late Bronze Age collapse.

The second assemblage, Dor L1, dates from the late 9th to early 8th century BCE and contains Phoenician-style jars and thin-walled bowls. Unlike Dor M, there is no evidence of Egyptian or Cypriot contact. Archaeological remains from this period show reduced imports and regional isolation, but the cargo contents prove that maritime trade persisted despite the decline in Dor’s influence.

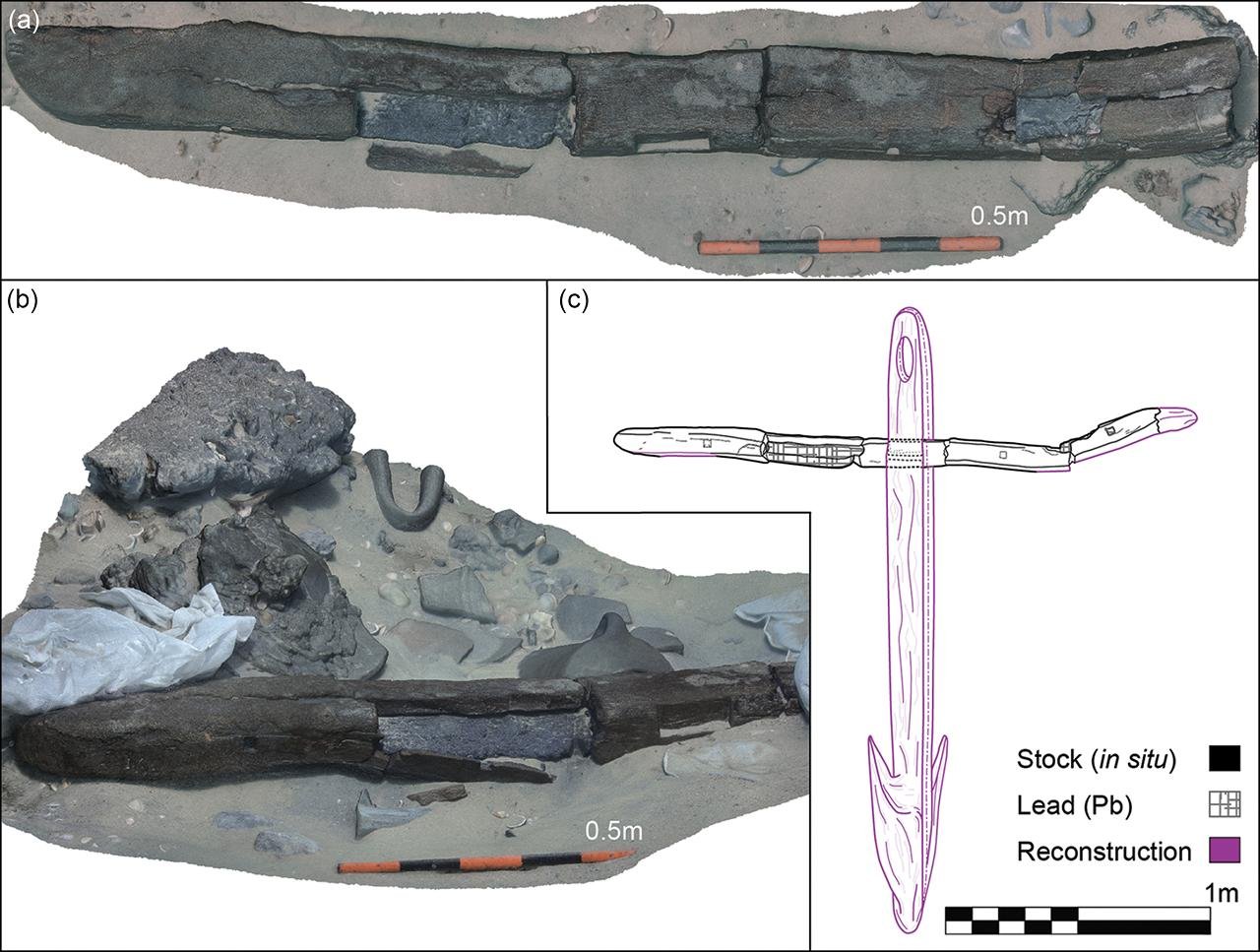

The most well-preserved and latest cargo is Dor L2, which dates to the late 7th or early 6th century BCE. It includes Cypriot-style basket-handle amphorae and iron blooms—intermediate products of iron smelting—and shows metal trade on an industrial scale. Radiocarbon dating assigns this cargo to a period when Dor was under Assyrian or Babylonian rule after having previously returned to Phoenician control. Similar finds from Anatolian coastal wrecks show that Dor was connected to an expanding maritime network that linked the eastern Mediterranean’s major powers.

Plant residues, including grape seeds and date pits found in amphorae, helped refine the dating and content of the cargoes. Together, they illustrate cycles of economic expansion and contraction linked to political change in the Iron Age Mediterranean world.

The study combines traditional underwater archaeology with cutting-edge digital technology such as 3D modeling, multispectral imaging, and digital mapping. The “cyber-archaeology” approach, established through a collaborative effort between UC San Diego’s Qualcomm Institute and the University of Haifa, enables accurate reconstruction of submerged trading routes and harbor structures.

So far, only a quarter of the Dor sandbar containing the cargoes has been excavated. Further excavation may yield additional artifacts, including fragments of ship hulls. Already at this early stage, the finds prove that Dor was a dynamic maritime center whose prosperity mirrored the rise and fall of regional empires.

These cargoes—representing 500 years of Iron Age history—demonstrate that despite shifting political powers, sea trade remained a constant force binding distant coastlines and shaping the ancient economy of the Mediterranean.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.