A new detailed analysis of archaeological evidence demonstrates that early human populations of southern South America relied on extinct megafauna—such as giant sloths, giant armadillos, and prehistoric horses—as a regular food source, rather than as occasional or opportunistic prey. The results defy common presumptions that these large animals were hardly affected by human hunting and that climate change was the exclusive force behind their extinction.

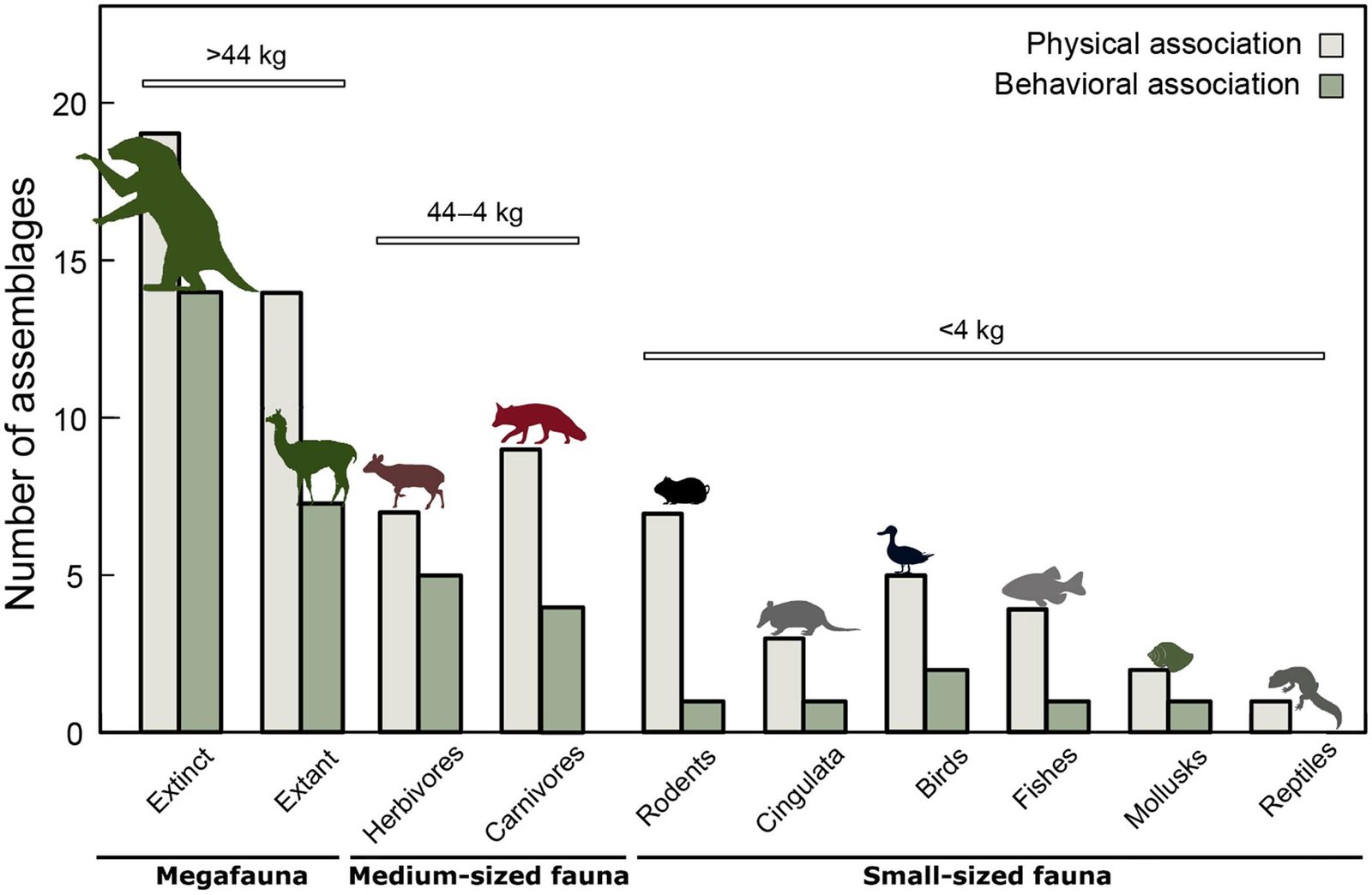

Published in Science Advances, the study pulls together data from 20 archaeological sites in present-day Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, all of which date from around 13,000 to 11,600 years ago. At 15 of the sites, more than 80% of the animal bones were from megafaunal species weighing more than 44 kilograms, including creatures that were previously considered too large for humans to hunt efficiently. Researchers searched for cut marks, fracture patterns, and spatial associations on the bones that reflected butchering and active human processing.

To account for prey selection, the team employed a prey-ranking model that considers the energetic return of different species relative to the effort required for hunting and processing them. Megafauna yielded greater caloric returns than small mammals in every case, suggesting that early humans focused on these large animals to maximize the efficiency of their hunting efforts. Giant sloths and armadillos, that is, were not simply consumed when they chanced to be encountered—they were highly preferred prey.

The findings provide strong quantitative evidence against one of the most cited criticisms of the “human overkill” hypothesis: that early humans primarily hunted small, manageable animals and therefore would not have been capable of inducing megafaunal extinctions. Instead, the study indicates that humans played central roles in late Pleistocene ecological dynamics, likely exerting heavy hunting pressure that contributed to the decline and eventual disappearance of these giants.

At some point after circa 11,600 years ago, following the reduction of megafauna populations, human diets expanded to include a wider range of surviving animals, such as guanacos, deer, and rodents. The dietary change appears to have been more out of necessity than preference, again backing the suspicion that megafaunal hunting had been the leading element of human subsistence strategies previously.

While the authors acknowledge that vegetation change, ecosystem dynamics, and climate change also influenced megafaunal declines, the study firmly places human predation at the center of the Quaternary extinction discussion in South America. Integrating a broad geographic and temporal dataset and applying a quantitative prey-ranking model, the study offers one of the clearest explanations yet of how early humans selected prey and interacted within their megafaunal environment.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.