About 42,000 years ago, early modern humans across Europe and the Near East began producing remarkably similar types of stone tools. Archaeologists had long assumed that these shared designs reflected a single tradition of technology—one passed west across the continent as Homo sapiens migrated from the Near East to Europe. But a new report published in the Journal of Human Evolution contradicts this pervasive perception, hypothesizing instead that toolmaking methods in the two places developed independently through parallel innovation and not through direct transmission.

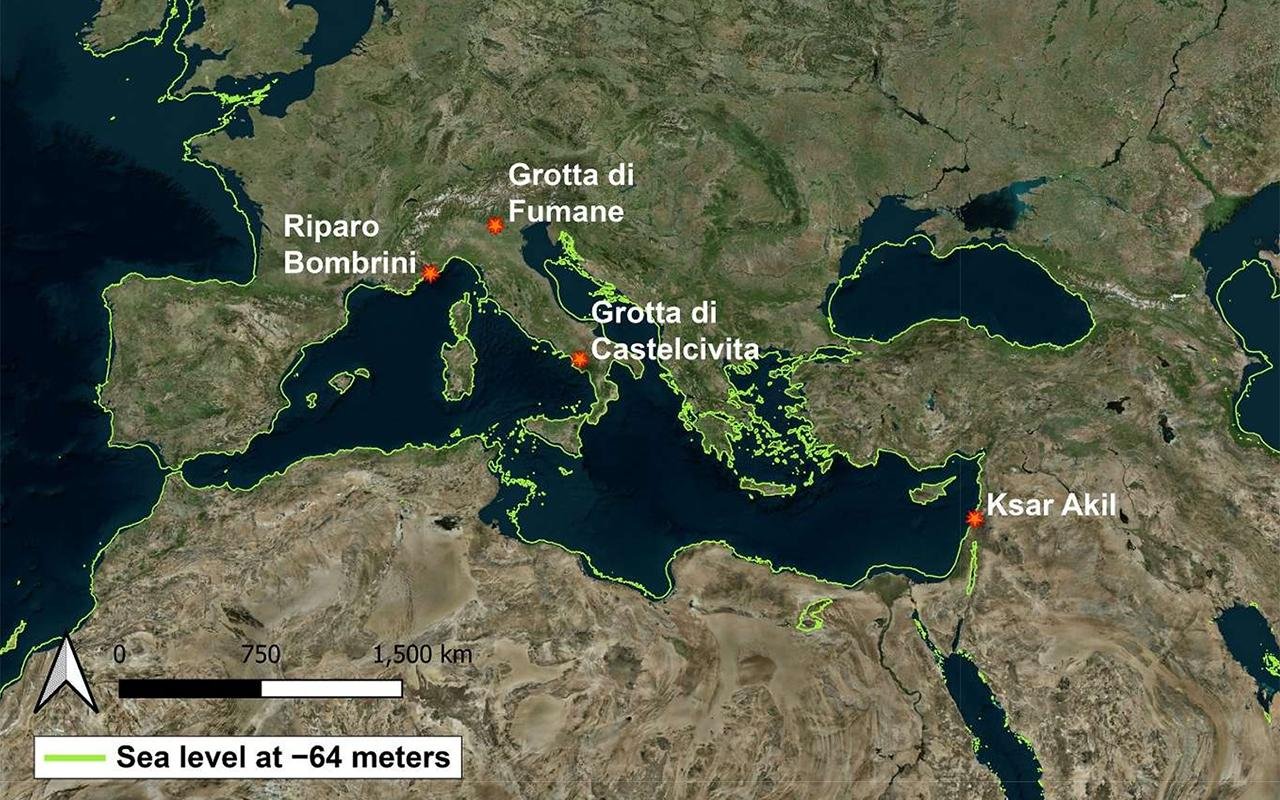

Scientists from the University of Tübingen and the University of Arizona made the first comprehensive, quantitative comparison of stone tool technologies of the Protoaurignacian culture in Europe and the Ahmarian culture in the Levant. The scientists studied thousands of objects from the Ksar Akil site in Lebanon and from several of the key Italian sites, including Grotta di Fumane, Riparo Bombrini, and Grotta di Castelcivita. The results reveal clear technological distinctions that contradict the Near Eastern origin theory of Europe’s earliest Upper Paleolithic industries.

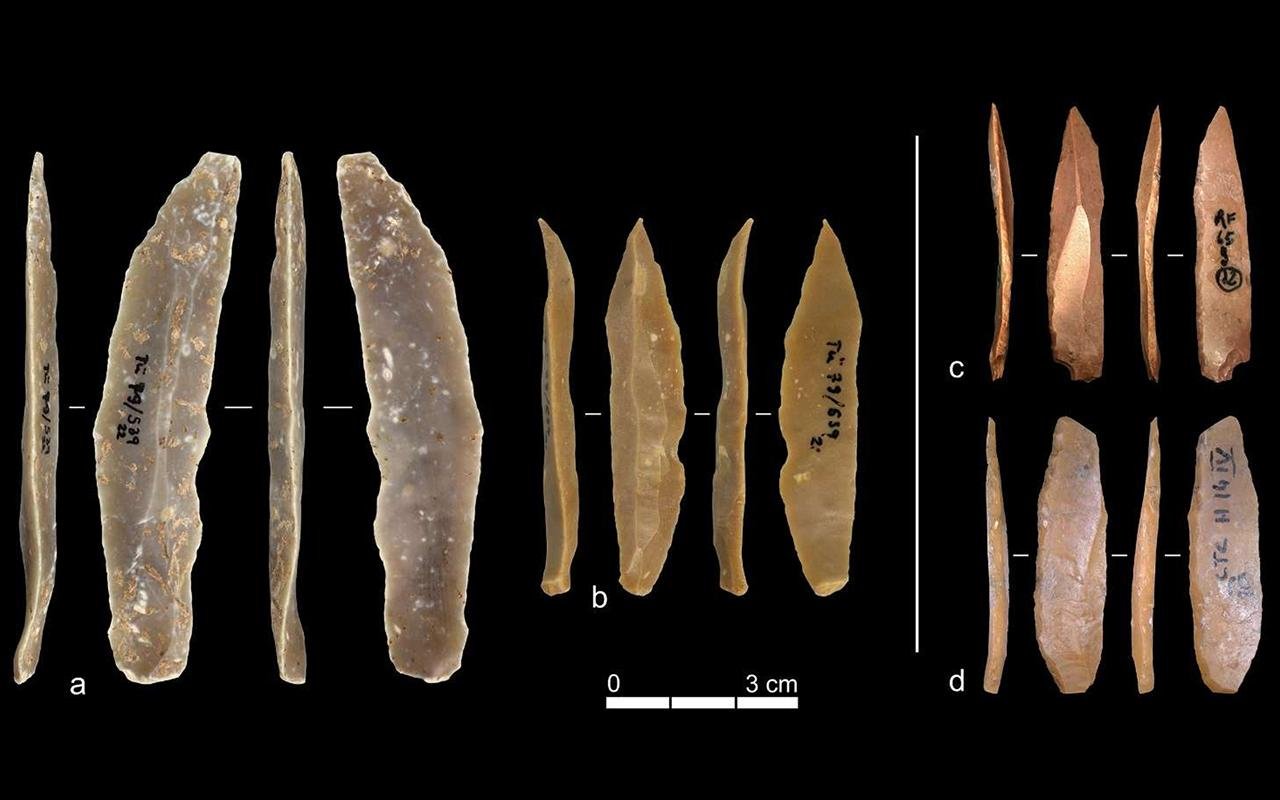

The Protoaurignacian, which appeared in southern Europe around 42,000 years ago, has long been regarded as a western offshoot of the Ahmarian culture and was often associated with the first Homo sapiens’ entry into Europe. Despite both producing small blades and bladelets used in composite tools—most likely hafted on spears or projectiles—the new research found that the tools were created by significantly different methods.

Ahmarian toolmakers at Ksar Akil largely used bidirectional core reduction, where stone was worked from two directions to produce standardized blades. Protoaurignacian groups in Italy, on the other hand, relied heavily on unidirectional techniques to produce much smaller bladelets from single platforms. In later post-Ahmarian layers at Ksar Akil, toolmakers eventually began producing twisted bladelets from specialized cores—a feature rarely found in European assemblages.

These differences, the researchers argue, indicate that the two regions went in distinct technological directions. Both cultures exhibited tendencies toward miniaturization, but their approaches to shaping and reducing stone cores diverged significantly. Far from illustrating a single technological lineage spreading across continents, the findings indicate convergent but independent developments, likely driven by similar adaptive pressures.

The research suggests that increased mobility and the wider use of multicomponent weapons—tools that have multiple stone inserts hafted within organic handles—may have helped bring this convergence. With hunter-gatherers facing new environments and the necessity for new solutions, they may have each developed comparable techniques independently to create more efficient and flexible tools.

These results oppose diffusionist models that attribute Europe’s Paleolithic innovation to a series of immigrations from the Near East. Instead, they highlight the importance of local innovation among established hunter-gatherers in Europe. The researchers propose that the Protoaurignacian was not an import from the Levant but rather one example of a broader technological trend toward smaller, more sophisticated toolkits.

Aside from its immediate applicability to stone tool studies, the study adds depth to the story of how modern humans spread and proliferated across Eurasia. It aligns with growing evidence that the spread of Homo sapiens was a complex, non-linear process involving both biological and cultural interactions between them and other human species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.