Archaeologists are reexamining one of the most fascinating artifacts ever discovered in the southern Levant: the ˁAin Samiya goblet, a small but remarkably intricate silver vessel dating to the Intermediate Bronze Age.

Discovered more than 55 years ago in a high-status tomb in the Judean Hills, the 8-centimeter goblet has long baffled scholars with its densely packed images of mythological scenes. For decades, many assumed that the images were connected to the Babylonian creation epic, the Enuma Elish. A new study, however, argues the vessel depicts a different—and much earlier—narrative about how ancient people imagined the cosmos taking shape.

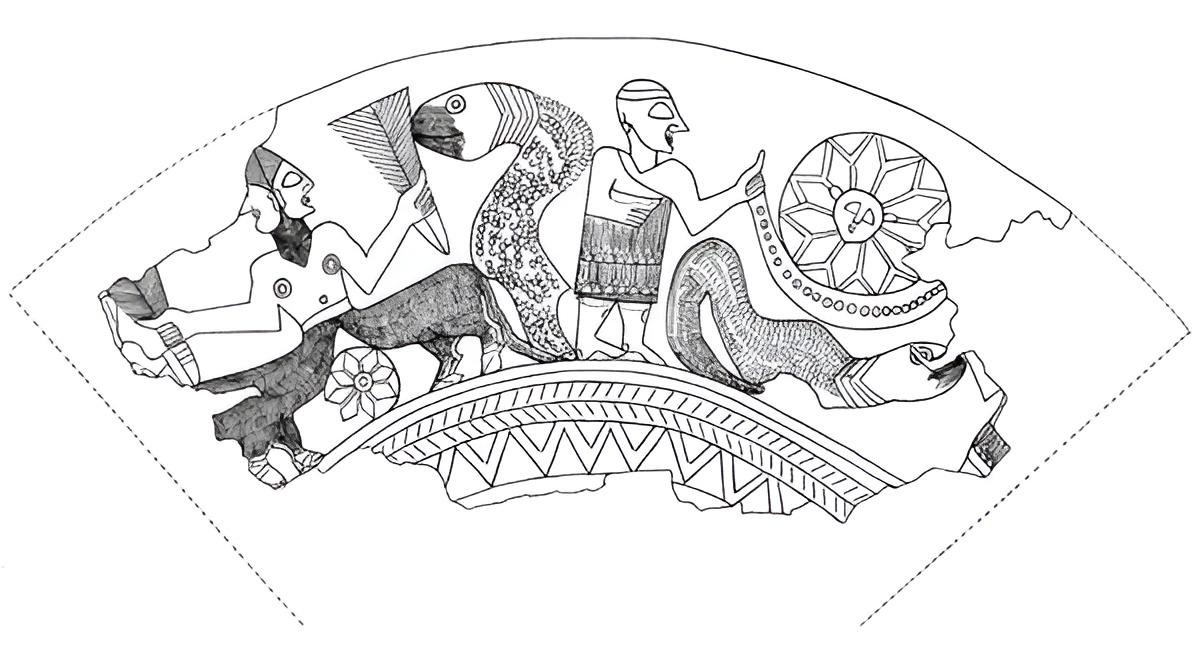

The goblet is generally regarded as the only true work of art to have survived from this period in the Levant. On its exterior, there are two interconnected scenes filled with hybrid creatures, serpents, plant motifs, and celestial symbols. Part of it has been damaged, leaving that part of the narrative incomplete, but enough survives to show a brilliant visual sequence. On one side is a chimera-like figure next to a large serpent. The human upper body of the figure merges into the legs of two bulls, and a small rosette, interpreted as a newborn sun, appears between its limbs. The scene has often been interpreted as chaotic and untamed, with the serpent symbolizing primordial disorder.

The second scene is quite the opposite. Two human figures lift the ends of a crescent form that cradles a radiant sun depicted face-on. The serpent now lies flat beneath the celestial boat, no longer the dominant feature. In the new study, the sequence indicates an orderly universe that emerges after chaos has been subdued. Instead of illustrating a particular myth, the imagery seems to symbolize the broader ancient Near Eastern idea of cosmic organization and renewal.

Researchers note that this provides strong parallels with Sumerian and Akkadian beliefs in the division of the world into two hemispheres—one for the living and one for the dead—both under the governance of the cyclical rebirth of the sun, moon, and seasons. The crescent, they note, represents the Celestial Boat, a common motif throughout Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and other areas, used to transport the sun across the sky. The progression from a small, newly “born” sun in the first scene to a powerful, fully developed sun in the second scene reveals a cosmological journey rather than a violent mythic battle.

Iconographic comparisons indicate that the designer of the goblet was a southern Mesopotamian artist who traveled to the north during the 23rd century BCE. The vessel itself, however, was likely produced in northern Syria, where access to silver was more readily available, and then moved south through trade routes. When it was placed in its tomb around 2200 BCE, the goblet may have been used ritually to guide the soul of the deceased along the same cyclical path as the rising sun.

Although some scholars still urge caution about definitive conclusions, the new study places the ˁAin Samiya goblet within a long tradition of cosmological storytelling stretching across the ancient Near East.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.