A new analysis of an inscribed alabaster vase from the Yale Babylonian Collection has produced the strongest scientific evidence to date that opium played a wider role in ancient Egyptian life than was previously known. The study, conducted by the Yale Ancient Pharmacology Program (YAPP), found multiple chemical markers of opiates inside the 2,500-year-old vessel, marking the first time the contents of an inscribed Egyptian alabastron have been scientifically confirmed.

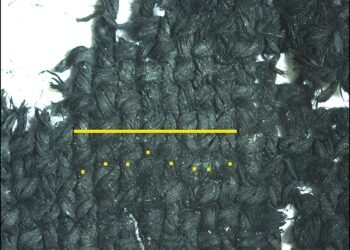

One of the few examples to survive intact, the vase was carved from calcite and dedicated to Xerxes I in four ancient languages. Its interior still retains dark, aromatic residues that YAPP researchers sampled using non-destructive methods developed over years of studying organic traces in archaeological collections.

They detected compounds such as morphine, thebaine, papaverine, noscapine, and hydrocotarnine, all substances strongly associated with opium. According to the research team, these results indicate that the production, storage, and use of opiates, rather than the calcite craft tradition, are associated with certain Egyptian alabaster vessels.

This finding constitutes a confirmation of earlier research conducted on objects excavated by Flinders Petrie at Sedment, Egypt, which similarly showed opiate residues in Cypriot juglets and plain alabaster vessels associated with an ordinary burial. These combined results thus illustrate the association of calcite vessels with opiates across the elite and everyday contexts of Achaemenid-period Mesopotamia and provincial Egypt. Achaemenid rulers, who formed one of the great imperial dynasties of ancient Iran, controlled a vast territory that stretched across much of the Near East. Their dominion extended from the Mediterranean to Central Asia and included Egypt, which became an important province of the empire. The pattern challenges older assumptions that such containers held cosmetics or perfume.

Researchers note that calcite seems to have been selected intentionally for its material properties; the implication is that such vessels were used both functionally and symbolically. Their distinctive shape and sheen may even have acted as recognizable markers of a cultural practice, much like specific paraphernalia associated with tobacco use today.

The new study also carries implications for one of the most famous archaeological assemblages in the world: the alabaster vessels from Tutankhamun’s tomb. Many of those containers were found with dark, sticky residues that early 20th-century chemical tests could not identify. Some were even carefully scraped by ancient looters, suggesting that the contents were highly valued. With the growing body of opiate evidence now spanning more than a millennium, researchers believe it is increasingly plausible that at least some of Tutankhamun’s vessels held similar substances.

The Yale team is continuing its investigation with additional analytical tools, including pXRF and pFTIR, as well as comparisons to calcite reference samples sourced from the Hatnub quarries in Egypt. Scholars hope to build a clearer picture of how opium circulated, how it was prepared, and why particular vessel types became tied to its use across the ancient world.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.