For centuries, the Stone of Scone—also known as the Stone of Destiny—has symbolized Scottish sovereignty and British monarchy alike. This 152-kilogram sandstone block, once used in the coronation of kings, has endured conquest, theft, and repair. Now, new research by Professor Sally Foster of the University of Stirling reveals a forgotten chapter of its story: dozens of missing fragments scattered across the world.

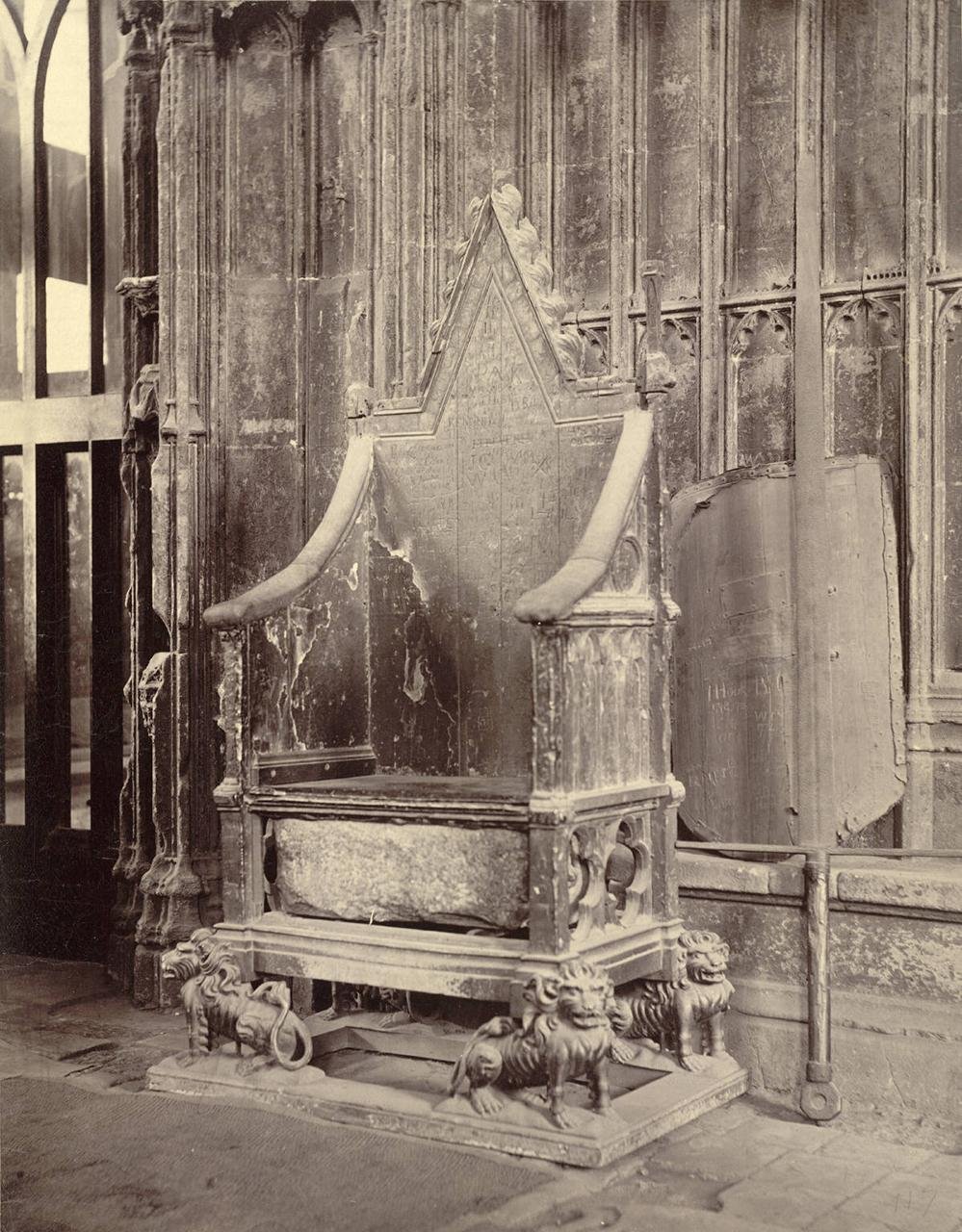

Foster’s study, published in The Antiquaries Journal, traces the fate of 34 pieces reportedly lost after the Stone’s dramatic 1950 removal from Westminster Abbey by four Scottish students determined to bring it home. The Stone, seized by King Edward I in 1296 and placed beneath the Coronation Chair, long stood as a symbol of England’s dominance over Scotland. Its removal, led by student Ian Hamilton, was seen as a nationalist act. But during the heist, the Stone broke in two. Stonemason Bertie Gray secretly repaired it—while keeping several small fragments as mementos.

Over the years, these fragments found surprising homes. Some became jewelry; one was set into a brooch for Hamilton’s girlfriend, another into a locket worn by politician Winnie Ewing. A piece reached Australia after Gray gifted it to a visiting woman, whose family later donated it to the Queensland Museum. According to Foster, such pieces “add new layers of meaning and value,” transforming the relic into something more personal and far-reaching.

Foster’s work involved tracking letters, photographs, and records to identify the fragments’ paths. Of the 34 missing pieces, she has verified 17, some passed down in families, others still missing. Her interdisciplinary research combines material culture and ethnography to explore how these shards—once dismissed as curios—carry powerful emotional and political weight.

The Stone itself has remained at the center of national debate. Officially returned to Scotland in 1996, it was displayed at Edinburgh Castle before moving in 2024 to the new Perth Museum. Yet its symbolic power endures: in 2023, activists attacked its glass case in Edinburgh, months after it was temporarily returned to Westminster for King Charles III’s coronation.

Foster’s study gained new relevance with the revelation that former First Minister Alex Salmond had received a fragment in 2008—a gift that reignited political controversy and proved the Stone’s continued ability to “galvanize Scotland and irritate the British establishment.”

For Foster, the fragments offer more than mystery. They reveal how heritage objects evolve through time, connecting people through shared identity and memory. “The fragmentation,” she writes, “has allowed the Stone to create personal connections far beyond Scotland.”

Seventeen pieces remain unaccounted for, but the search continues. Each rediscovered shard not only fills a historical gap but deepens the story of a relic that refuses to rest—an enduring emblem of Scotland’s past, and its ongoing quest for self-definition.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.