A remarkably preserved Stone Age dog burial found in a bog in central Sweden has completely reshaped the current understanding of funerary rituals practiced among prehistoric fishing communities. The burial dates back approximately 5,000 years and was unearthed during archaeological surveys linked to the construction of a new high-speed railway near the hamlet of Gerstaberg, located southwest of Stockholm.

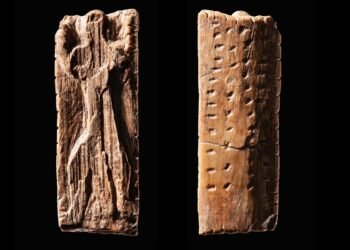

The remains were discovered in the waterlogged sediments of Logsjömossen, a wetland that was once a clear, shallow lake used for fishing. Alongside the near-complete dog skeleton was a 25-centimeter-long highly polished bone dagger, which had been made from elk or red deer bone. This unusual close association of finds indicates that they were deliberately deposited together in a single event, rather than lost or discarded separately.

Analysis of the bones shows that the animal was a large, strong male that was between three and six years of age, with a shoulder height of about 52 centimeters. The bones also reveal that the animal had an active lifestyle.

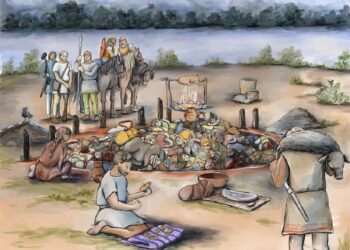

It is believed by archaeologists that the animal was placed inside a skin or leather container that was filled with stones and carefully lowered into the lake at a depth of about 1.5 meters and at a distance of about 30 to 40 meters from the ancient shoreline. This suggests that the placement of the animal was not a practical disposal method but rather a ceremonial act.

Though dog remains have been discovered dating from the Stone Age in Scandinavia, complete burial sites such as this are a very rare occurrence indeed. Even more surprisingly, there is the presence of the bone dagger, which is often associated with symbolic or ritual meaning. This type of dagger has previously been found in wetlands, indicating that watery environments held special significance for prehistoric people.

The burial of the dog was not an isolated archaeological find. Excavations across this 3,500-square-meter site revealed extensive evidence of fishing activity, including wooden stakes set into the lakebed, posts that might have supported piers, stones that would serve as anchors or net weights, as well as an archaeological feature that resembles a two-meter-long structure made of interwoven branches interpreted as a fish trap. Trampled areas can be observed in the mud, suggesting that people regularly stood and moved around on the lake bottom while tending their gear.

Taken together, these discoveries offer a rich picture of what the landscape must have been like, where daily subsistence activities and ritual practices became inextricably entwined. Future scientific analysis, including radiocarbon dating, isotope studies, and DNA testing, promises to reveal a more accurate timeline and further insights into the dog’s diet, health, and origins. In turn, this could illuminate how the Stone Age fishing communities lived, how they moved through their environment, and how they expressed their beliefs through deliberate actions in the landscape they inhabited.

More information: Arkeologerna

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.