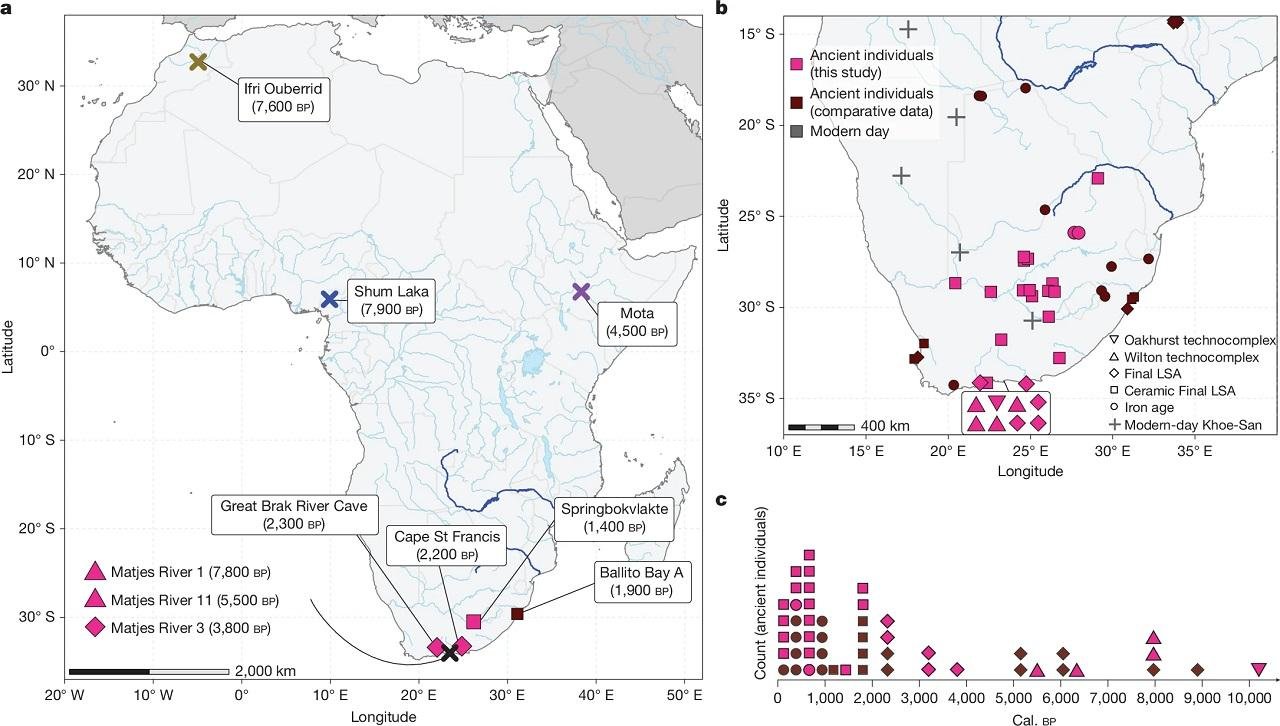

A new genetic study indicates that ancient communities in southern Africa lived in long-term isolation, developing a distinct set of genetic traits that shaped early Homo sapiens. Researchers analyzed the entire genomes of 28 individuals who lived between approximately 10,200 and 150 years ago in regions south of the Limpopo River. Their findings, published in Nature, provide some of the strongest evidence to date that southern Africa played a major role in human evolution.

According to the research, this region represents a genetically isolated population of humans for at least 100,000 years and possibly more like 200,000 years. The genetic patterns of individuals living over 1,400 years ago fell outside the range of variation of modern peoples, including present-day Khoe-San. This ancient southern African ancestry contained an astonishing degree of diversity, including genetic variants that have vanished in other groups.

For much of that long period, there is no evidence of external gene flow into the south. At sites like the Matjes River Rock Shelter, archaeological layers reveal identifiable cultural changes in tools and techniques over many millennia, but the DNA suggests that the same population endured through these changes. This stability stands in contrast to patterns in many other parts of the world, where technological or cultural transitions are often associated with new waves of migrants.

Genetic models suggest that southern Africa might have functioned as a refugium, a favorable area for humans to survive through changing climates. The ancient population mostly lived in isolation, but there were occasional migrations northward during milder climatic periods. Traces of their DNA turn up in individuals from present-day Malawi around 8,000 years ago, suggesting small-scale movement out of the region long before any major influx arrived in the south.

Perhaps the most intriguing result of the study is the finding of dozens of genetic variants unique to Homo sapiens, which were widespread in ancient southern Africans. Many of these changes seem linked to kidney function, fluid balance, and sweating, characteristics that might have given early humans an advantage in body temperature regulation. Some variants relate to neuron growth, cognitive abilities, and immune function, suggesting that aspects of human attention, brain development, and complex thinking may be rooted in these ancient populations.

Scientists estimate that roughly half of all genetic variation present in modern humans can be traced to this prehistoric southern African group. Much of that genetic legacy persists in modern San communities of Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa, which retain up to 80 percent of ancient southern African ancestry.

The study challenges long-standing assumptions that Homo sapiens originated only in eastern Africa. Instead, the evidence shows that southern Africa supported longstanding populations of our species and made key contributions to the genetic and behavioral traits of modern humans.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.