Researchers have recently published an article in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal that provides a new perspective on why the Chinchorro culture in northern Chile began artificially mummifying their dead more than 7,000 years ago. While the practice may be seen only as a ritual or technological innovation, the study suggests that mummification may have emerged as an emotional response to widespread infant mortality in their communities and functioned as grief processing within small coastal communities of the Atacama Desert.

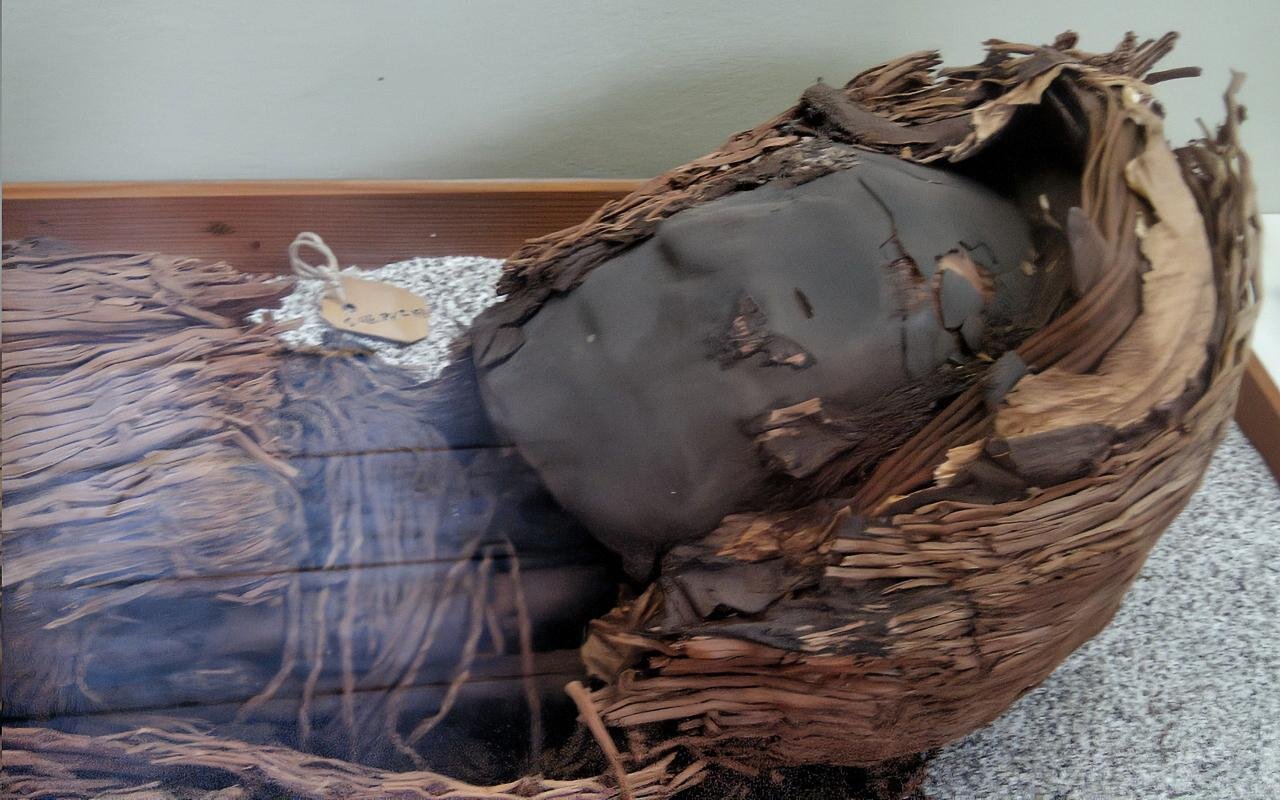

The Chinchorro were mobile hunter-gatherers who were skilled fishermen as well as skilled artisans, and also had unusually complex mortuary practices. They produced elaborately prepared artificial mummies that predate Egyptian mummification by millennia, dating to between roughly 7,000 and 3,500 years ago. The process was quite intensive and creative: they disassembled bodies, reinforced them with sticks, fibers, clay, and soil, and then carefully reassembled them. Facial features and genitals were often recreated, and the bodies were finally coated in black manganese paste or, in later periods, red ocher.

The study asserts that the initial phase of this tradition was centered on infants and young children, especially in areas such as the Camarones Valley. This region was heavily contaminated with arsenic at levels above safe thresholds. Long-term exposure to arsenic would have caused miscarriages, stillbirths, and high infant mortality, which must have put an immense emotional strain on families whose survival depended on successful reproduction. In this context, transforming the bodies of these children into well-designed and visually striking forms may have aided parents by providing a means through which they could cope with loss while also symbolically keeping the dead within the social world of the living.

Over generations, what may have begun as an intimate, emotionally charged response came to be a defining cultural practice for all individuals, regardless of age and sex. The mummies displayed standardized styles and elaborate ornamentation, which suggests that social identity, visibility, and communal memory became intertwined with mortuary art.

However, there is an alarming side to the tradition that is exposed by this research. The use of manganese pigments likely exposed the Chinchorro to toxic substances. Bioarchaeological analyses reveal elevated manganese levels in many individuals, which could have led to neurological disorders resembling Parkinsonian syndromes. These risks may have led to shifts in mortuary practices among the Chinchorro, including the eventual abandonment of black manganese pigments in favor of red ocher.

The Chinchorro mummies are not only among the most impressive expressions of prehistoric mortuary art, but also represent a significant example of how ancient societies confronted grief, loss, and memory through their creativity.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.