A recently conducted study has pushed back the origins of a sophisticated form of metalworking in Western Europe, revealing Bronze Age communities in southeastern Spain experimenting with complex techniques of casting far earlier than previously acknowledged. The research focuses on a distinctive silver bangle from the El Argar culture, showing the first evidence for lost-wax casting of silver objects within the region.

It was recovered in 1884 from Grave 292 at El Argar, a key site linked to a society that flourished in southeastern Iberia between approximately 2200 and 1550 BC. The El Argar communities are already well known for their unusually rich funerary assemblages, particularly their extensive use of silver at a time when most Bronze Age cultures relied primarily on copper or bronze. Thousands of objects excavated in the late 19th century by the brothers Henri and Louis Siret eventually found their way into the collections of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, where the bracelet is preserved today.

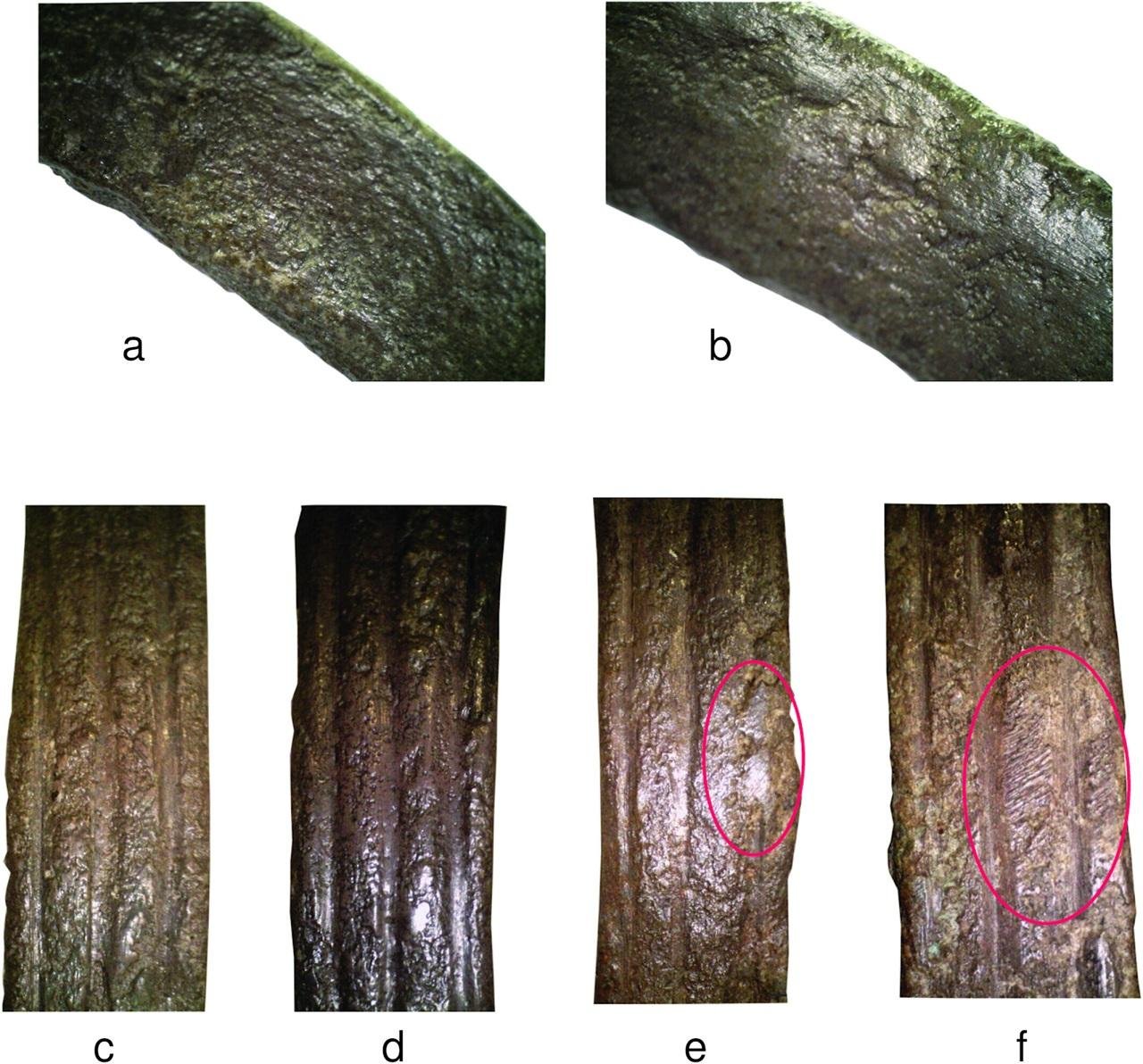

What distinguishes this bangle is not only its form but also its method of manufacturing. Shaped like a continuous strip with parallel grooves along its exterior, the object shows traces that could not be explained by traditional hammering or simple casting methods. Detailed metallurgical analysis indicated that it was made using the lost-wax technique, a sophisticated process in which a model in wax was created and encased in clay, then fired to remove the wax, and finally filled with molten metal. While this technique is well-documented for later classical sculpture, such a find for silver items in Western Europe during the early Bronze Age had not been confirmed previously.

These results suggest that the metalworking of El Argar was innovative and more diverse in terms of technique than previously thought. Other silver objects from the same cultural context could also have been produced using similar methods, but corrosion and the loss of some artefacts make their firm identification problematic. If confirmed, this would imply that the use of lost-wax casting in Iberia has been underestimated.

Curiously, the bracelet is not particularly refined, and one may wonder how and for what reasons such an exacting technique was adopted. Evidence suggests that production was closely connected with elite contexts, as remains of beeswax and experimental casting come primarily from areas related to high-status burials. This would suggest that access to the technique may have been restricted and perhaps controlled by elite households or by a group of specialized craftspeople. This also leaves open the possibility that the social value of the process was considered more important than flawless workmanship.

More broadly, the find challenges the traditional view of early Bronze Age craft organization in the western Mediterranean: rather than a single, uniform level of skill, El Argar metallurgy could have been based on a hierarchy of expertise, experimentation, and selective knowledge transmission.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.