Archaeologists in the Iraqi Kurdistan region have been able to reconstruct the process of making pottery at an Iron Age urban center over 2,800 years ago. Archaeological excavations at the Dinka Settlement Complex, which is a large site in the Peshdar Plain, have uncovered a well-preserved pottery workshop from which every aspect of the process can be traced, from the raw clay and fuel to kilns and finished products.

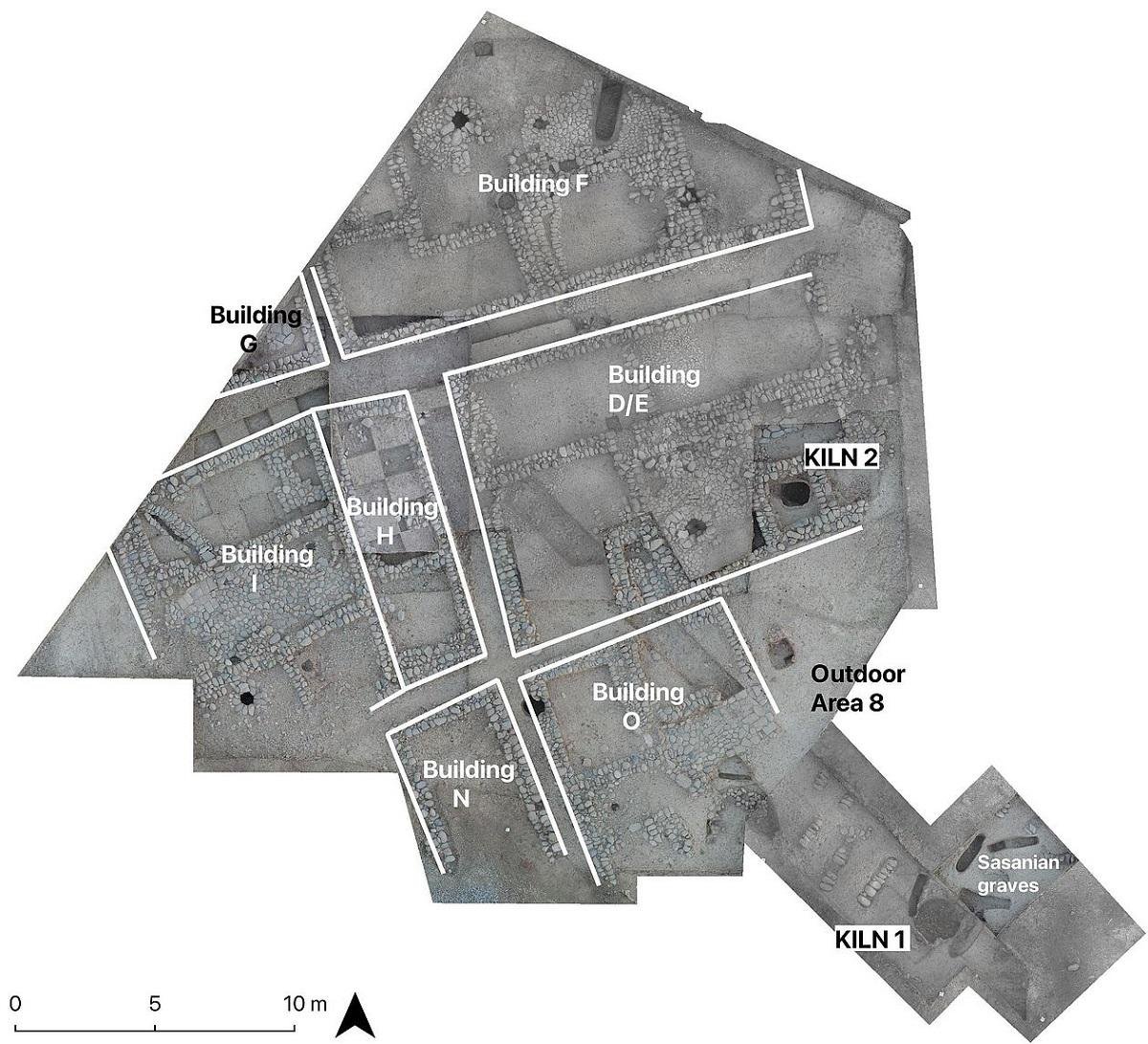

The workshop has been revealed in what is known as Gird-i Bazar, dating to around 1200–800 BCE. Two kilns, along with dense deposits of production debris and intact sediment layers, were discovered in this settlement, which is now among the most extensively excavated Iron Age sites in the Zagros region. In contrast to previous research that centered on ceramics, this study placed equal emphasis on the firing installations, thus providing a more complete perspective on ancient pyrotechnology.

The interdisciplinary team of researchers examined pottery shards, kiln linings, local clays, and firing residues. They employed various scientific methods, such as mineralogical, microscopic, and soil analyses. These techniques allowed them to determine kiln construction, fuel types, firing temperature, and kiln use histories. The findings of this research indicate that potters relied on simple updraught kilns and low-temperature firing, usually below 900 °C, under oxidative conditions. The firing rate was slow, with a short firing time, and vessels of different shapes and functions were often fired together.

Although the vessels differed in shape and finishing, possibly indicative of their intended uses, they shared the same technological framework. Differences in early stages of manufacturing did not signify competing craft traditions, but rather a modular system, in which potters followed flexible routines before converging on standardized firing practices. Long-standing techniques such as wheel-coiling and burnishing persisted into the Iron Age, indicative of a conservative yet efficient production tradition.

Evidence from the settlement suggests that the production of pottery was not confined to a single location. Geophysical surveys have shown other kilns to be situated elsewhere in the complex, indicating a network of workshops that followed common procedures. This pattern confirms that the production of ceramics exceeded household needs and served wider community or regional demands. The close integration of the workshops and the urban layout, as well as the evidence of kiln reuse, suggests a dynamic settlement shaped by changing economic and social priorities.

Taken together, these results suggest a degree of organization and coordination that has been previously underestimated for Iron Age communities in the Zagros. The production of pottery was clearly embedded in daily urban life, and such production was managed through shared knowledge and efficient resource use, and possibly centralized oversight.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.