What is now considered the earliest mule known from the western Mediterranean and continental Europe was identified by researchers at the Iron Age site of Hort d’en Grimau in the Penedès region of northeastern Iberia. The discovery, recently presented in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, pushes back the timeline for equid hybridization in Europe by several centuries and highlights the reach of early Mediterranean exchange networks.

The remains were first excavated in 1986 from a pit, likely a silo reused for storage, in which the anatomical remains of a small equid lay alongside the partially burned bones of a woman. This well-preserved material, which is kept today in Vilafranca del Penedès, was re-analyzed using radiocarbon dating, ancient DNA, zooarchaeology, and isotopic analysis. By such methods, it was confirmed that the animal in question was indeed a female mule from the 8th to 6th century BCE, a period marked by increased Phoenician activity along the Iberian coastline.

The Phoenicians introduced domestic donkeys into the region during the Early Iron Age, establishing trade routes that brought new goods, technologies, and animals into Iberia. Because mules are hybrids between a mare and a male donkey, their presence in such an early context implies that knowledge of equid crossbreeding, long practiced in the Near East, may have reached Iberia much earlier than previously assumed.

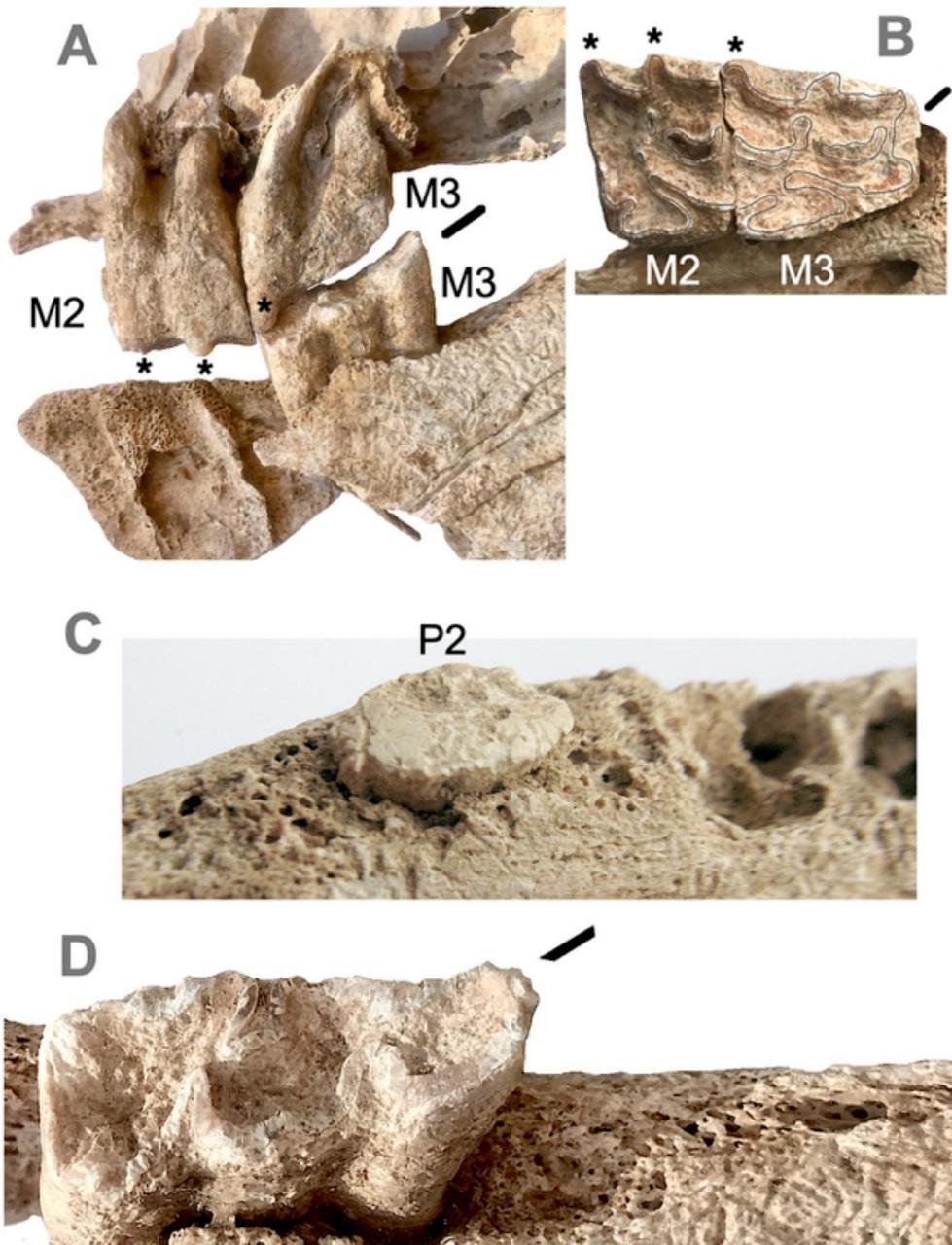

Analyses reveal that this animal had horse and donkey skeletal features and showed age-related pathologies, particularly in the jaws, which are consistent with being handled and ridden regularly. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes indicate a diet rich in cultivated cereals, which implies intentional foddering and possibly stabling. Such signs suggest a valuable working animal that was maintained on high-energy feed and therefore had an important economic role within this local community.

Whether this mule was bred locally or imported remains unclear. It could have been produced by crossing local horses with newly arrived Phoenician donkeys, but it could have been brought into the peninsula already hybridized. Ongoing genetic and isotopic research will try to answer these questions by comparing local findings to populations of the Levant, North Africa, and wider Europe.

The associated human burial adds a further layer of importance. In a number of Early Iron Age sites in northeastern Iberia, women were on occasion interred with equids, a pattern quite distinct from later funerary traditions. During the Second Iron Age, horse remains are found mainly in male cremation graves, which are related to status and martial symbolism. The earlier pattern—although uncommon—might be related to local practice influenced by long-term contact with Phoenician communities.

The finding of the Hort d’en Grimau mule constitutes a unique insight into early hybrid animal management, long-distance cultural interaction, and changing funerary practices. Above all, it redefines the chronology of mule breeding in Europe by showing that such hybridization was already underway in the region centuries before Roman influence took hold.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.