Archaeologists have sought to understand life in Britain before and during Roman rule, and they have discovered large differences in health between rural and urban communities. A recent examination of human remains from southern and central Britain shows that the Roman occupation brought long-term health challenges, but these problems were largely limited to crowded towns founded under Roman influence. Outside the cities, many earlier traditions persisted, and overall well-being appears to have changed far less.

The period under consideration can be viewed as a turning point in British history. When Rome took control in CE 43, it introduced new forms of administration, expanded settlement networks, and people began living in towns. Historical records relating to that period mark these changes as signs of ‘civilization’, but archaeological evidence shows that the shift toward denser population centers brought new risks, too. Unfamiliar diseases, more consumption of cereal grains, and social inequalities that limited access to resources all contributed to environmental stress.

To grasp how these forces shaped everyday life has long been complicated by the nature of Iron Age burial practices. It had been common practice for pre-Roman communities to fragment or cremate the dead. Consequently, there were no complete adult skeletons available for researchers to analyze. Infants, however, were sometimes interred intact. To analyze the short- and long-term health patterns, the study focused on the skeletal remains of young children alongside adult females of reproductive age. This approach draws on the DOHaD (Developmental Origins of Health and Disease) hypothesis, which suggests that experiences in the earliest years of life can leave biological signatures that affect health throughout adulthood and even in future generations.

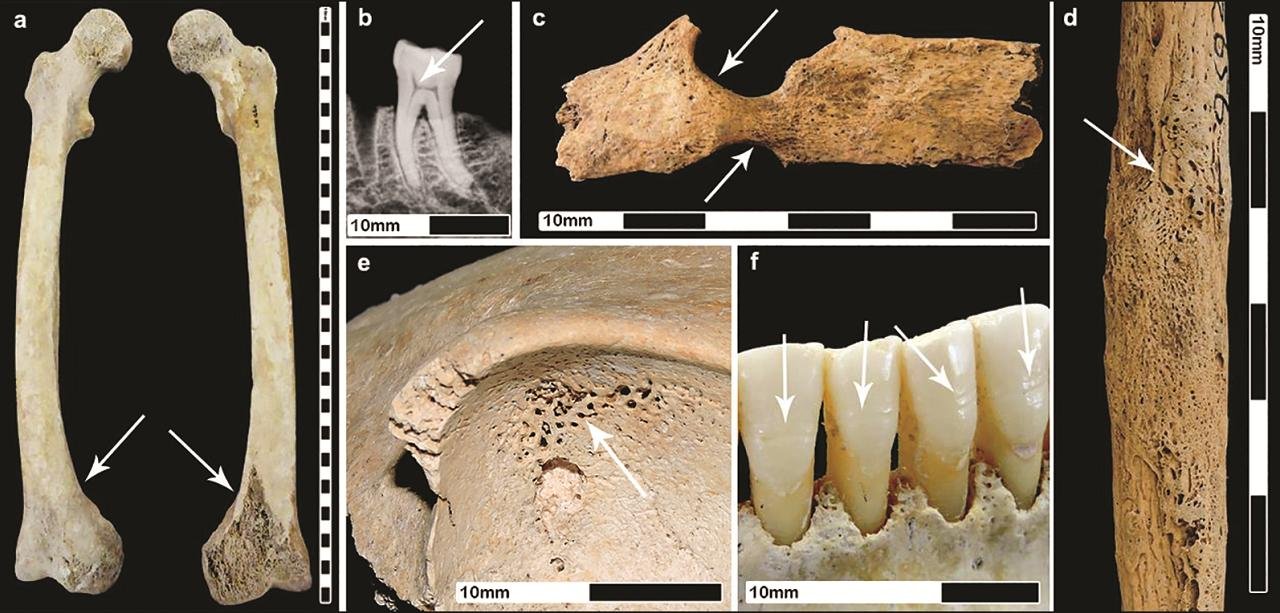

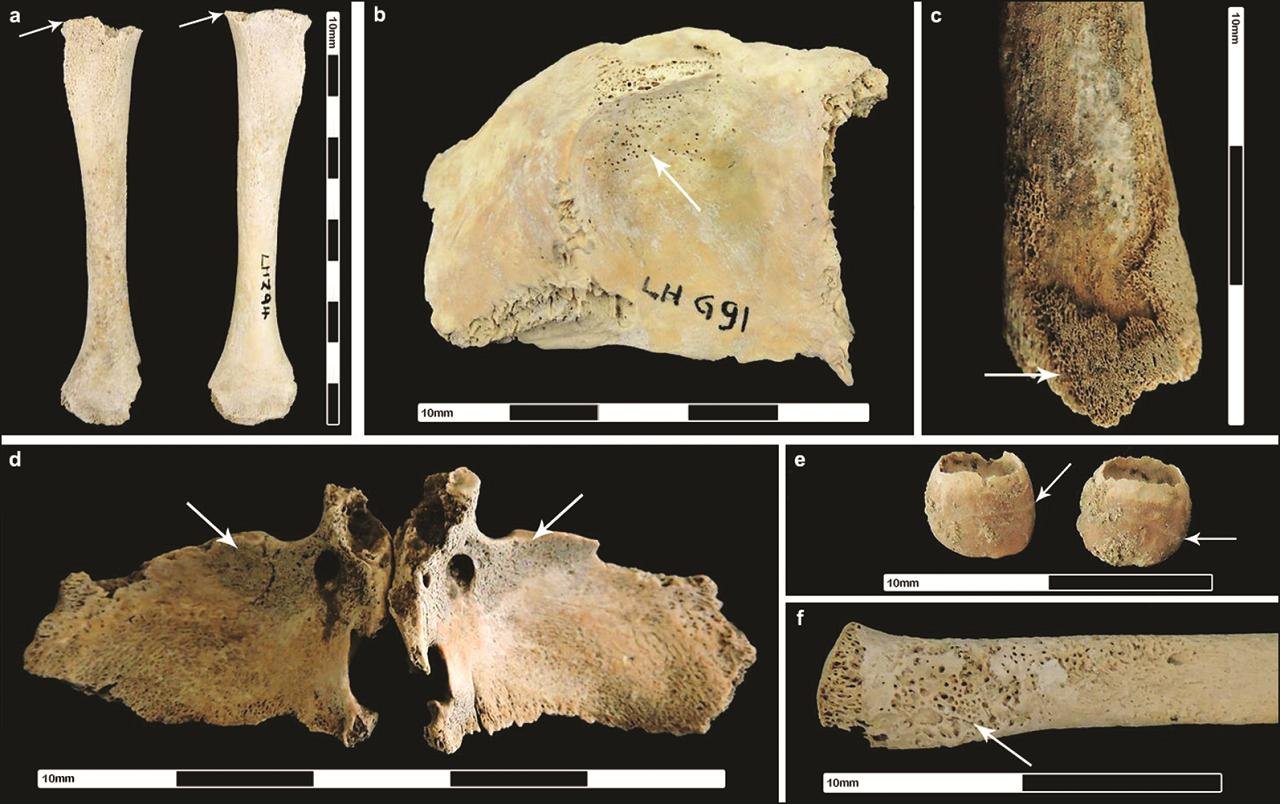

A total of 646 skeletons were analyzed, including 372 non-adults who were under 3.5 years old and 274 adult females. The data were collected from Iron Age settlements, rural Roman settlements, and Roman urban centers. The health factors that were considered include skeletal lesions, signs of nutritional stress, and markers of disease exposure. The findings indicate a clear divide: Roman-period urban populations showed a significant increase in negative health markers compared to both Iron Age and rural Roman communities. Living conditions within Roman city centers appear to have been influenced by overcrowding, pollution, and frequent contact with pathogens. Lead, commonly used within Roman water systems and other infrastructure, could have posed an extra risk.

However, for rural populations, there were slight increases in pathogen risk, but no significantly lower health. These findings suggest that many Iron Age lifeways persisted, as well as more stable access to food sources and cleaner living environments, which were maintained well into the Roman period outside the main urban hubs. It challenges some traditional perceptions about how Roman culture rapidly transformed the entire region.

By examining the impact of these changes on mothers and babies through the generations, it becomes possible to build a more detailed picture of life in Roman Britain. The study reveals how large social changes can shape population health unevenly, with consequences that echo well beyond a single generation.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.