About 5,500 to 6,000 years ago, hunter-fisher-gatherers lived across what is now Finland. These communities, known to archaeologists as the Typical Comb Ware culture, built semi-subterranean houses, traveled along waterways, and relied on fishing, hunting, and small-scale plant use. They buried their dead in graves marked by bright red ochre, an iron-rich earth pigment with clear ritual value.

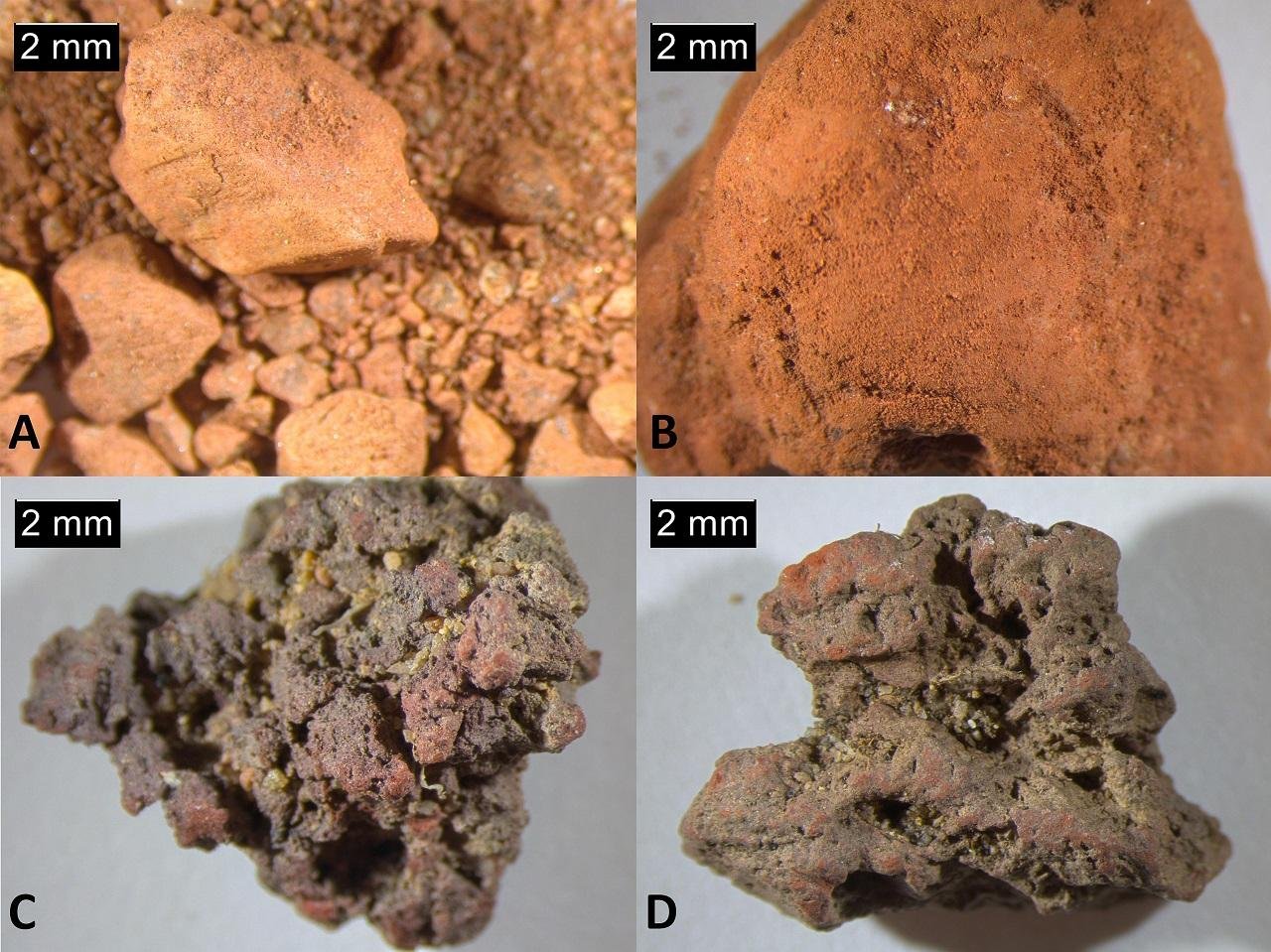

A new study in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports examines how these groups selected and moved ochre. Researchers analyzed samples from eight archaeological sites across Finland, taken from both graves and settlement areas. The team used non-invasive energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectrometry. These methods preserved the original material while measuring elemental composition.

The results show three main chemical groups of ochre rather than a unique signature at each site. Some chemically similar samples appear at locations up to 500 kilometers apart. This pattern points to long-distance movement of the pigment. Such distances match known exchange routes that moved other materials, including Baltic amber and slate ornaments from the Lake Onega region. Ochre formed part of the same social and exchange networks that linked distant communities.

The study also compared ochre from domestic spaces and burial contexts. At several sites, the chemical makeup of ochre from graves differed from samples found in living areas. This pattern suggests deliberate choices tied to funerary practice rather than random use of local soil. In some cemeteries, individuals buried close together received ochre from different chemical groups. Even within a single grave, separate objects or body areas sometimes carried pigment from distinct sources.

These patterns show that color alone did not drive selection. Communities placed value on where the pigment came from and how people obtained it. Transport over long distances required planning, travel, and social ties. The presence of non-local ochre in graves signals links between groups and shared ritual traditions.

The research also highlights regional procurement. Some ochre groups cluster around certain parts of Finland, which points to preferred sources known to nearby communities. Other pigments moved between regions in both directions. Exchange worked as a network rather than a one way flow.

By combining chemical data with archaeological context, the study reveals how early forager societies organized materials, memory, and identity. Ochre served as more than decoration. People selected specific types for specific individuals and settings, which tied the dead to places and relationships that stretched far beyond a single village.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.