Archaeologists working in central Spain have documented strong evidence for a long-standing Neanderthal practice focused on the collection and placement of large animal skulls deep inside Des Cubierta Cave. The findings come from a detailed study of Level 3, a Middle Paleolithic deposit dated to cold phases between about 135,000 and 43,000 years ago.

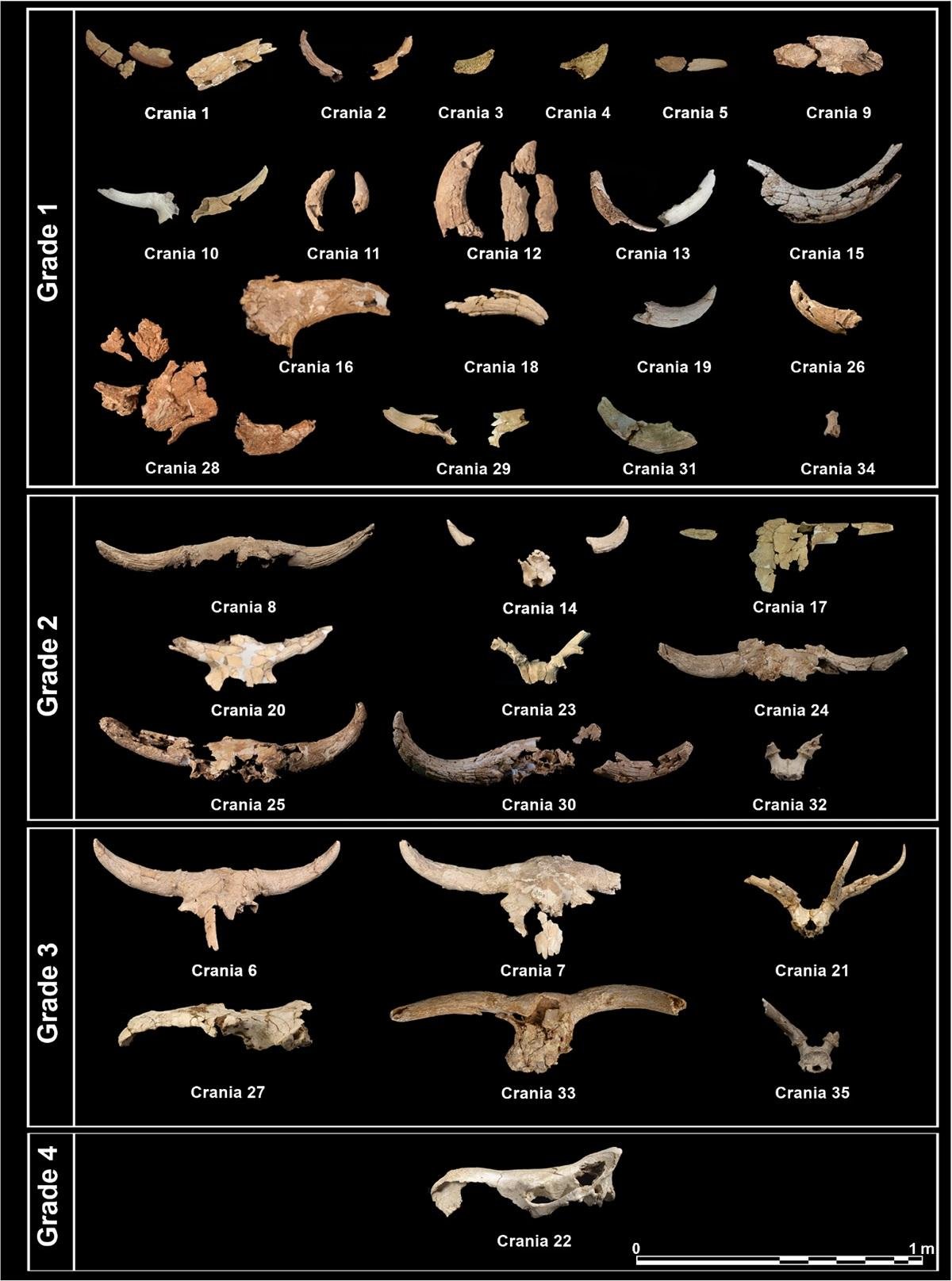

Excavations revealed 35 skulls from large hoofed mammals, including steppe bison and aurochs. Most skulls lack lower jaws, and every specimen belongs to a horned or antlered species. Researchers also recovered more than 1,400 stone tools in the same layer. These tools match Mousterian technology, a stone tool tradition linked with Neanderthals. Traces of fire use also appear in this level.

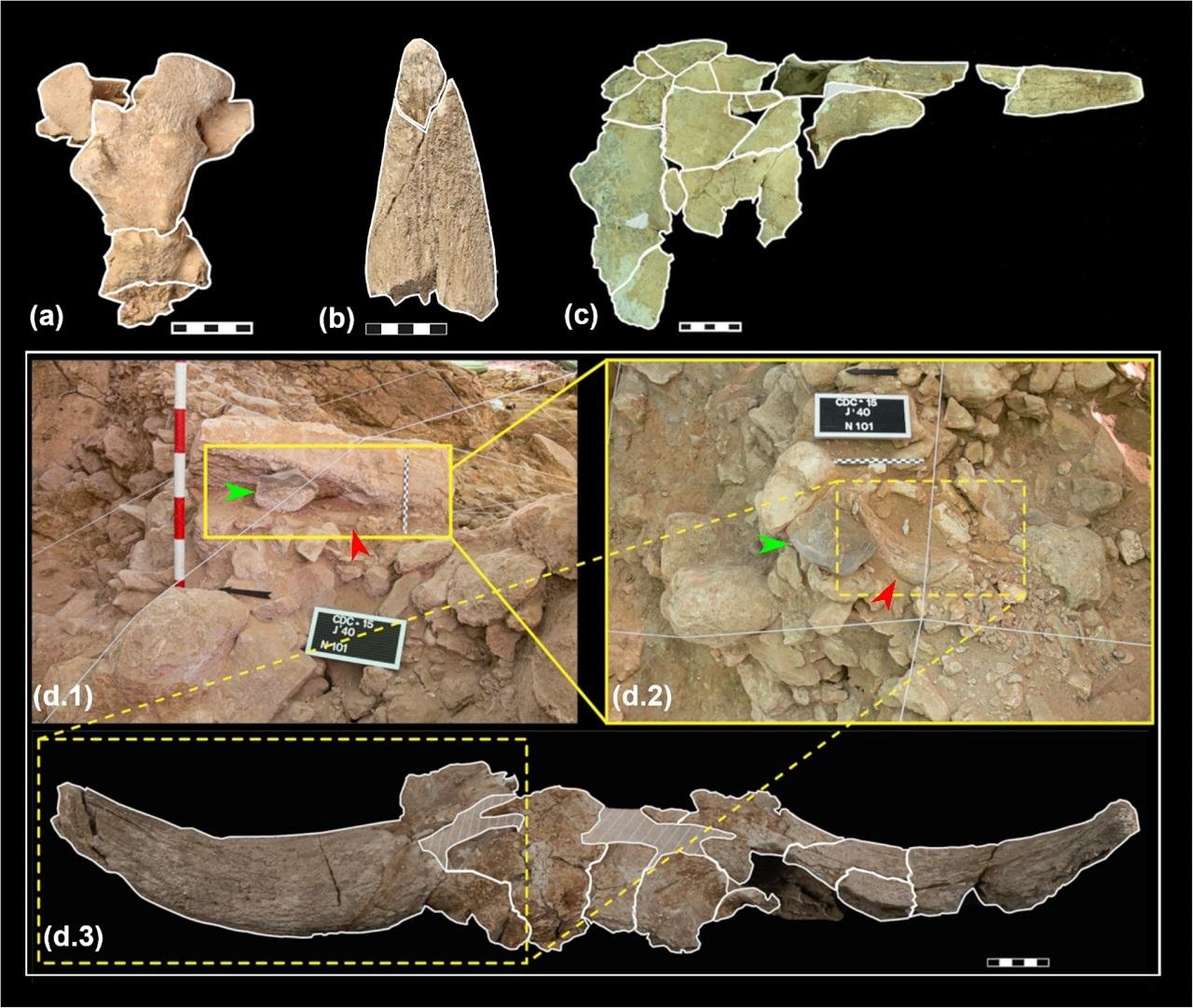

At first glance, the bone cluster looked disordered due to repeated rockfalls inside the cave over thousands of years. To separate natural processes from human activity, the team mapped the exact positions of stones, bones, and tools. They compared the spread of rockfall debris with the distribution of archaeological materials. Geological fragments formed a cone-shaped deposit, while skulls and tools followed different spatial patterns. This contrast supports deliberate placement by Neanderthals rather than random burial by falling rock.

Geostatistical analysis of stone sizes helped define the shape and growth of the debris cone. Size sorting and changes in stone density point to pauses in sediment buildup, which created stable surfaces inside the cave at different times. Archaeological materials rest above early rockfall layers, showing human visits occurred after initial debris accumulation.

Bone refitting offered another line of evidence. Researchers matched broken skull fragments found close together, which indicates limited movement after deposition. The cave shape and the slope of the sediment cone influenced how far pieces shifted. Central areas of the gallery, near the cone’s middle, preserved skulls in better condition. Southern zones, where the passage narrows and surfaces become uneven, show heavier fragmentation due to gravity, erosion, and soil processes.

The repeated appearance of horned skulls in specific cave areas suggests patterned behavior rather than food storage or butchery waste. Other animal bones common in living areas appear in much lower numbers here. The cave section holding the skulls shows no clear signs of daily habitation, which points toward a special purpose for this space.

Researchers conclude Neanderthals returned to this location many times over a long span. Each visit added new skulls to earlier deposits. Such continuity implies shared knowledge passed across generations. The consistent focus on horned heads, careful placement, and use of a non-domestic cave chamber support the interpretation of a cultural tradition with symbolic meaning.

Beyond behavioral insights, the study highlights the value of combining spatial statistics, geology, and bone analysis in complex cave settings. Careful separation of natural and human processes allowed a clearer view of how Neanderthals shaped this underground environment. Des Cubierta Cave now stands as one of the strongest cases for structured, repeated deposition of animal skulls by Neanderthals in Europe, adding weight to growing evidence for socially learned traditions among these ancient humans.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.