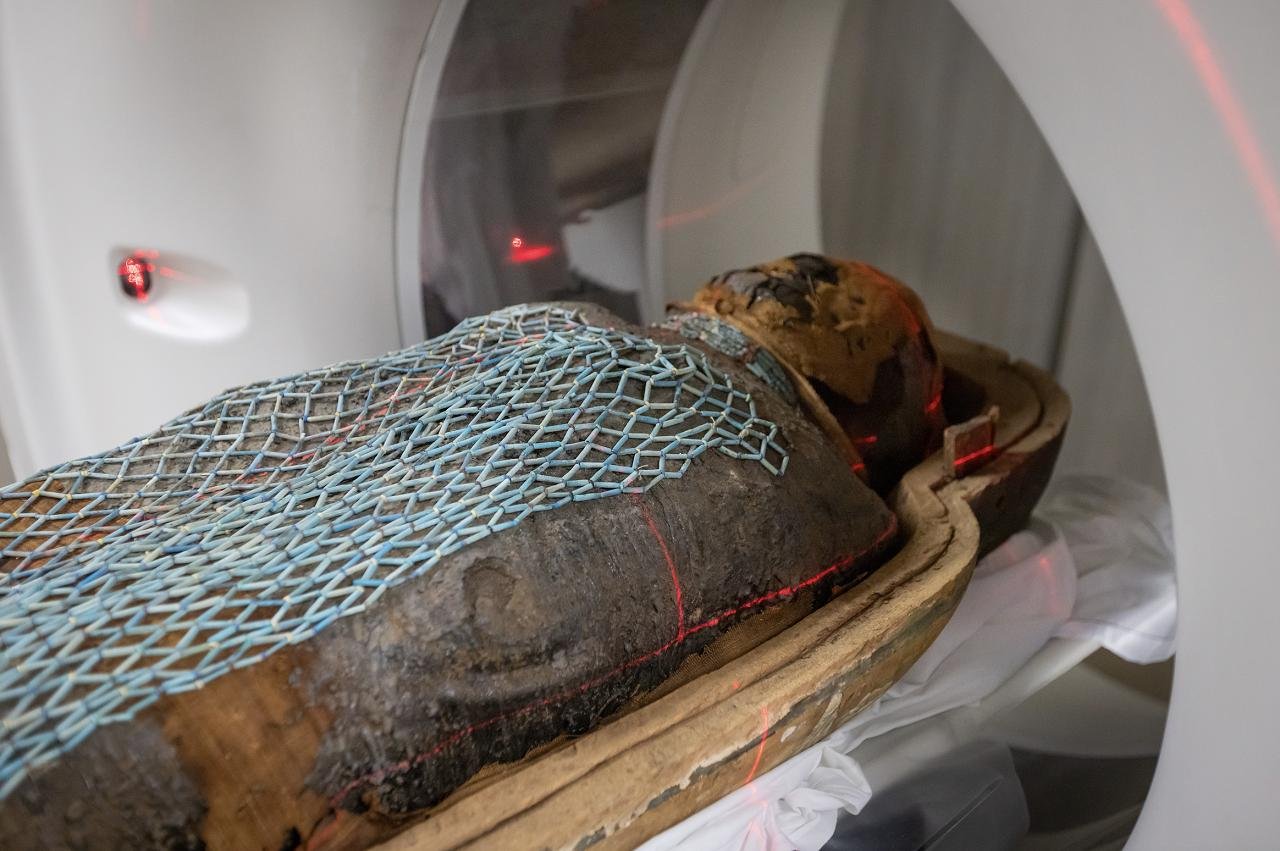

Radiologists at Keck Medicine of USC examined two ancient Egyptian mummies using high-resolution CT scanning, producing detailed views of bodies preserved for more than two millennia. The project focused on two priests, Nes Min from around 330 BCE and Nes Hor from around 190 BCE. Researchers scanned each body while it was still resting inside the lower half of a heavy sarcophagus weighing about 200 pounds.

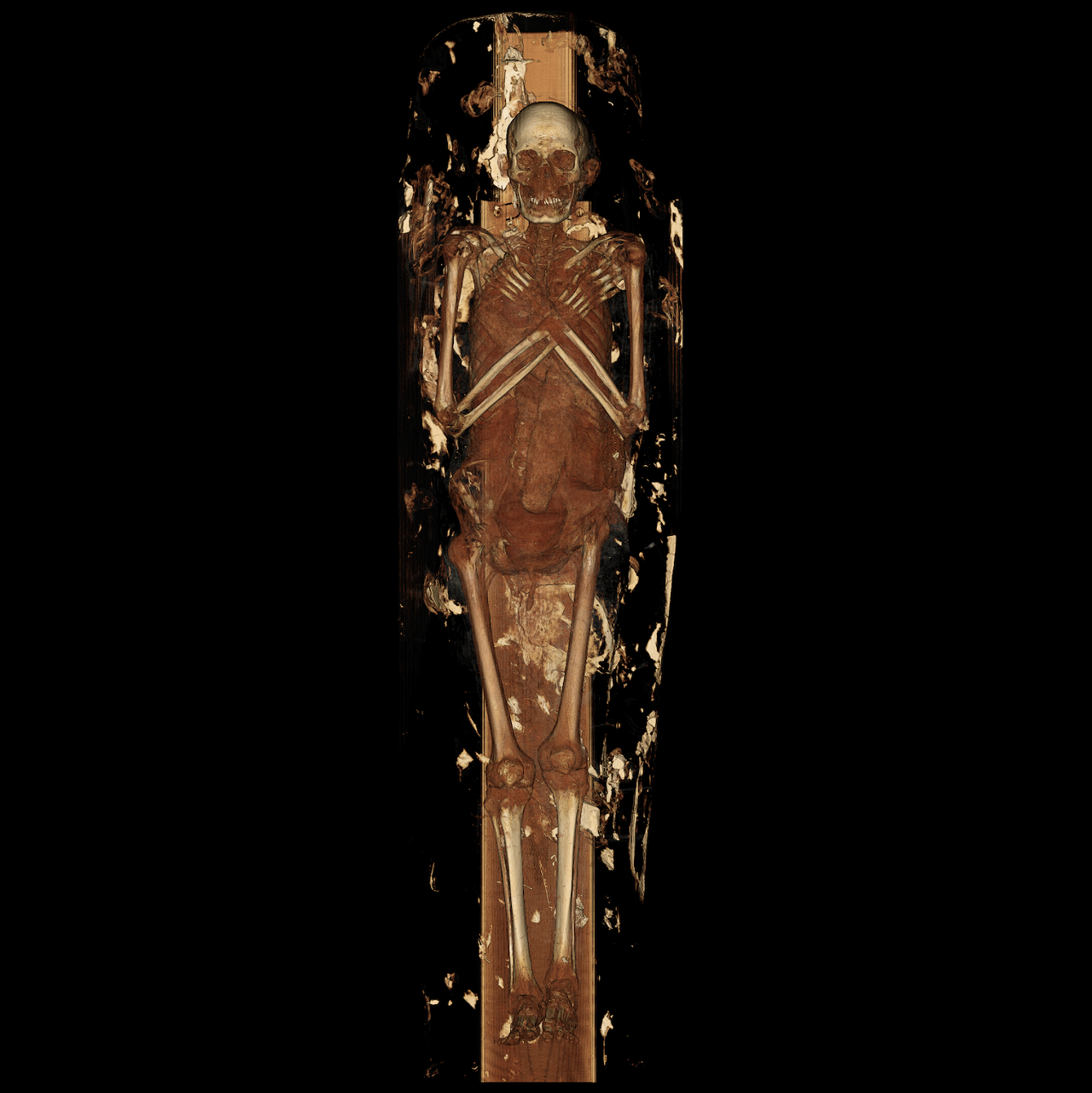

The scanner captured thin cross sections across the entire body. Specialists combined hundreds of slices into three-dimensional digital models. These models revealed fine physical details, including eyelids, lips, and bone structure in the face. Such features provided a clearer sense of individual appearance rather than that of a wrapped figure.

The scans also recorded signs of aging and disease. Nes Min showed damage in the lower spine. One lumbar vertebra had collapsed, a pattern linked with long-term strain and age-related wear. Modern clinics see similar degeneration in older adults with chronic back pain. Nes Hor displayed a different set of problems. Imaging showed advanced decay in several teeth and severe deterioration in one hip joint. Joint damage of this type often leads to limited movement and pain during walking. Bone condition suggested that Nes Hor reached an older age at death than Nes Min.

Burial objects appeared in the images as well. Nes Min rested with small items shaped like scarab beetles and a fish. These objects, placed within the wrappings, had stayed hidden from view for more than 2,000 years. CT data allowed for the measurement and study of those items without disturbing the mummy.

After imaging, visualization experts built digital reconstructions of the skeletons and selected artifacts. The team then produced life-size prints of the skulls, spines, hips, and burial objects using medical-grade 3D printers. Visitors to an exhibition at the California Science Center will see those replicas alongside the mummies and digital displays. The exhibit opens February 7 and presents the material as part of Mummies of the World.

The same imaging and printing workflow serves present-day medicine. Hospitals use CT or MRI scans to create digital 3D models of organs such as the liver, heart, or pelvis. Surgeons study these models before complex operations. Physical prints help with planning incisions, selecting implant sizes, and practicing difficult steps. Access to nearly two dozen printers at the USC Center for Innovation in Medical Visualization supports both clinical care and research projects like the mummy study.

Holding a physical model also helps patients understand anatomy and planned procedures. Doctors report clearer discussions when a person handles a replica of a tumor or damaged joint. The mummy project shows how medical imaging tools designed for living patients also support research on ancient people. Detailed scans preserve fragile remains while still allowing close study of health, injury, and daily life in ancient Egypt.

More information: University of Southern California

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.