Archaeologists at the Dong Xa site in northern Vietnam have identified the earliest direct evidence of intentional tooth blackening in the country. The teeth came from an Iron Age burial dated to around 2,000 years ago. Chemical traces preserved on the enamel match materials described in historical records of Vietnamese tooth staining. The findings appear in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Tooth blackening formed part of daily and social life in Vietnam into the twentieth century. Ethnographic accounts describe several methods. Some people rubbed their teeth with tannin-rich plants or soot from burned coconut shells. Others followed a longer process using iron-based mixtures applied over about 20 days. This treatment produced a deep black surface with a glossy finish. By the early 1900s, many ethnic groups across Vietnam practiced tooth blackening across different regions and social groups.

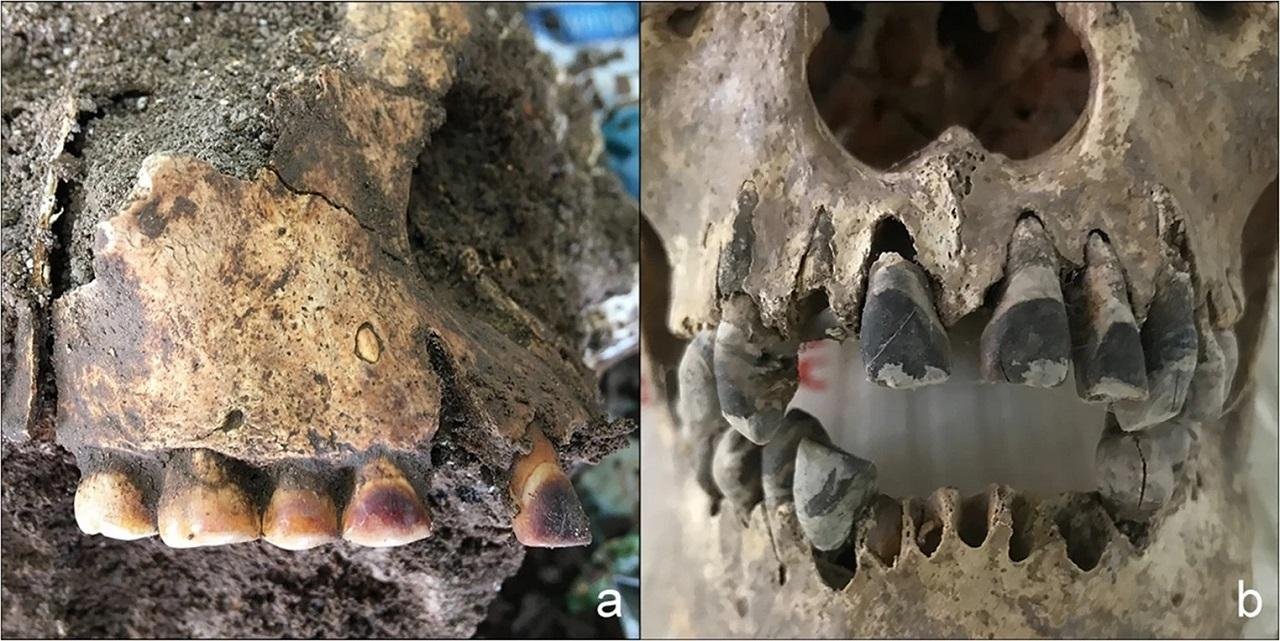

When archaeologists encounter darkened teeth in ancient burials, diet and burial conditions often provide the first explanation. Betel chewing, for example, leaves stains on enamel. The Dong Xa team wanted to test whether the discoloration on three individuals reflected deliberate cosmetic treatment rather than natural or dietary staining.

Researchers removed small samples from the tooth surfaces and examined them with scanning electron microscopy and portable X-ray fluorescence. These techniques allowed them to measure the elemental composition without causing visible damage. The enamel showed high levels of iron and sulfur. Together, these elements point to iron salts combined with tannins. When mixed, they form iron tannate compounds known for their dark color and long-lasting effect.

To strengthen their case, the team recreated a staining mixture based on historical descriptions, similar to iron gall ink. They applied the solution to a modern animal tooth and analyzed the surface after treatment. The experimental tooth showed the same pattern of elevated iron and sulfur found in the 2,000-year-old samples. The close match supports the view that the Dong Xa individuals underwent a controlled staining process.

The burial context places these individuals within the Dong Son cultural complex. This society is known for bronze drums, weapons, and wide exchange networks across mainland Southeast Asia. Archaeologists have often relied on images cast on bronze artifacts to reconstruct personal appearance during this period. Those images show feathered headdresses and tattooed bodies. The blackened teeth from Dong Xa add another form of bodily modification to this picture.

The study extends the documented history of tooth blackening in Vietnam by about two millennia. It also provides a clear chemical signature for identifying similar practices in other archaeological settings. By focusing on elemental evidence, researchers now have a practical method for separating intentional staining from natural discoloration. The teeth from Dong Xa connect Iron Age communities with later Vietnamese traditions through a shared approach to appearance and identity.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.