In 2023, archaeologists excavating a grave in Nördlingen, Swabia, recovered a bronze sword dating to the Middle Bronze Age, more than 3,400 years ago. The weapon belongs to the rare group of octagonal swords known from southern Germany. After the find drew wide attention, the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments arranged for a detailed scientific study in Berlin to answer questions about how the sword was built and decorated.

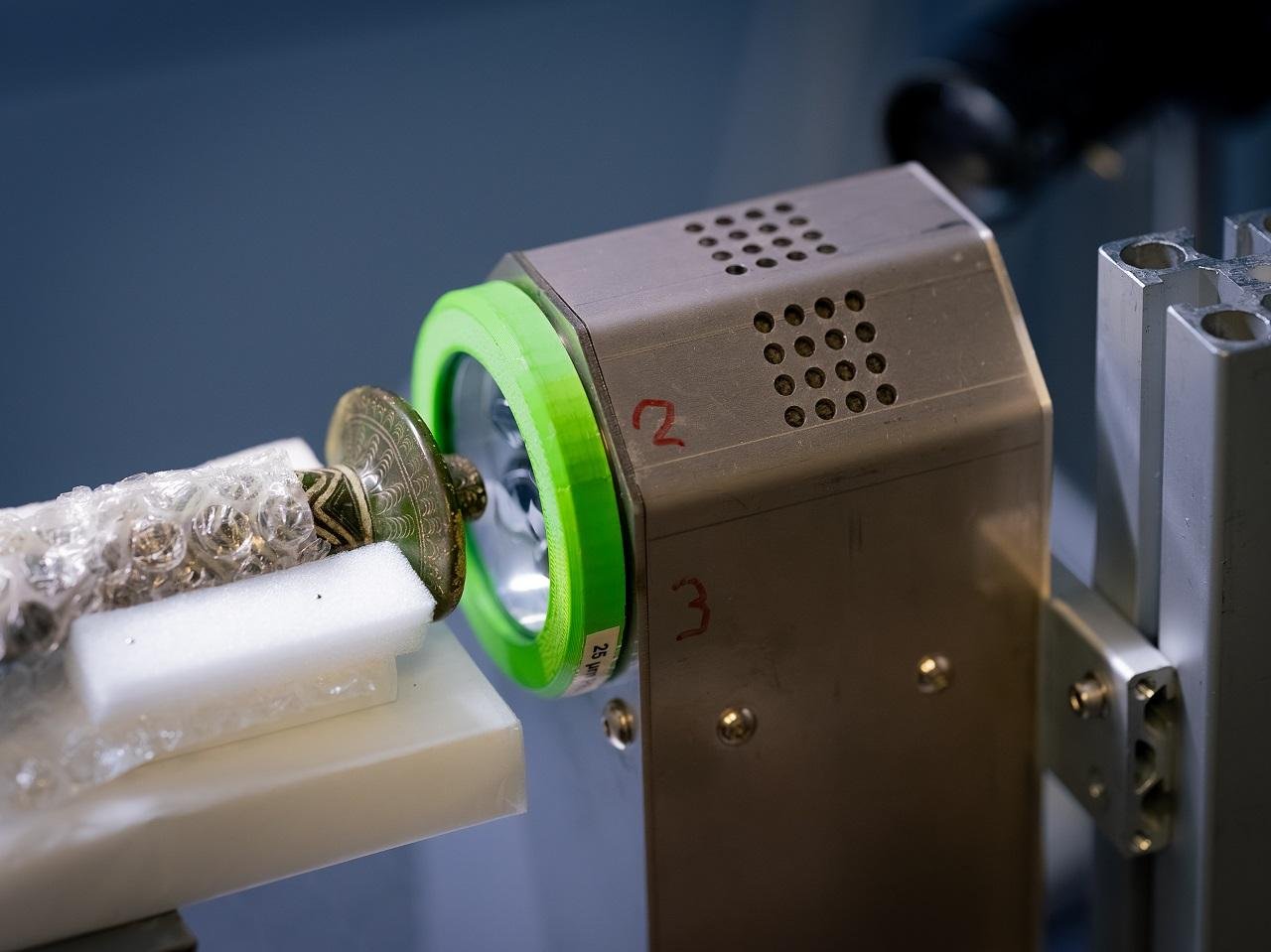

The team relied on non-destructive methods. At the Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin, specialists carried out high-resolution computed tomography and X-ray diffraction. At the BESSY II synchrotron, researchers from the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing conducted X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy at a dedicated beamline. Together, these approaches allowed the group to examine the structure, composition, and internal stress without taking samples.

The sword’s condition made such work worthwhile. Parts of the blade still retain a metallic sheen, and the cutting edge remains nearly sharp. The pommel and pommel plate display deep geometric grooves arranged in a regular pattern. Those features raised questions about how the weapon had been assembled and how the decoration had been inserted.

Computed tomography provided the first answers. The three-dimensional X-ray model shows that the blade continues into the hilt as a tang, an extension of the blade itself. The maker clamped this tang into the hilt and secured it with rivets. The scan resolution reached a level where small tool marks and changes in material density became visible, offering evidence of shaping and finishing techniques.

The grooves on the pommel appeared to contain a contrasting material. At first glance, tin seemed a likely candidate because of its softness. X-ray fluorescence analysis told a different story. By exposing the surface to intense synchrotron radiation, researchers measured element-specific X-rays emitted by the atoms within the metal. The inlays consist of copper wires joined together. Only minor traces of tin and small amounts of lead appeared, most likely linked to the bronze alloy rather than the decoration.

The choice of copper required careful work. Comparable copper wire inlays appear in other Bronze Age finds, though such decoration demanded precision. To increase contrast between the reddish copper and the golden bronze base, the surface may have undergone chemical darkening. Researchers suggest a patination process to create visual contrast.

Another set of tests focused on residual stress within the crystalline structure of the metal. Heating, casting, hammering, forging, and quenching leave measurable patterns of compressive and tensile stress. By mapping these patterns, the team reconstructed parts of the production sequence, including forging and finishing stages.

Full evaluation of the data continues. Early conclusions point to southern Germany as the likely production region, one of the two main distribution centers for octagonal swords during the Bronze Age in Germany. Researchers hope further analysis will narrow the origin to a specific workshop. Through imaging and spectroscopic study, the Nördlingen sword now provides technical evidence about metalworking practices in the second millennium BCE.

More information: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.