Archaeologists studying the Tartessian site of Casas del Turuñuelo in western Spain have reconstructed the lives of animals sacrificed during a large ritual event about 2,500 years ago. The work focuses on chemical signals preserved in animal teeth, which record details about diet, water sources, and movement across different landscapes.

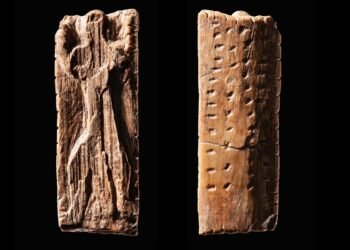

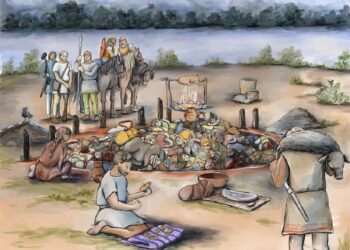

Casas del Turuñuelo lies in the Guadiana River basin in the province of Badajoz. Excavations have revealed a large adobe building from the late Iron Age. Near the end of the fifth century BCE, people held a banquet inside the structure. Soon after, they sacrificed at least 52 animals in stages in the main courtyard, which covers about 125 square meters. The group included 41 equids. After the ceremony, the building was burned and sealed under a mound of earth. This burial preserved the remains in unusual detail.

Researchers analyzed 23 teeth from 19 animals found in the building and courtyard. The sample included 12 equids, four cattle, and three sheep or goats. Scientists removed small samples along the length of each tooth crown. Because enamel forms over time, each section reflects a different period in an animal’s early life.

The team measured three types of isotopes. Strontium isotopes reflect local geology and help identify where an animal lived. Carbon isotopes provide information about plant foods and whether animals ate mainly natural pasture or received fodder. Oxygen isotopes relate to drinking water and seasonal climate patterns.

To interpret the data, researchers first built a local reference for strontium. Modern vegetation no longer grows at the site, so they tested animal bones buried there, which absorb strontium from the surrounding soil. They also collected modern plant samples from different parts of Extremadura and used published data to map regional variation.

Most horses in the study show strontium values that differ from the local signature. Their ratios match areas in the western Guadiana valley, including zones near present-day Mérida and Badajoz. One horse displays a distinct signal linked to areas farther east or north. These patterns indicate that the horses did not come from a single herd raised at the site. Instead, people brought them from multiple locations.

Carbon and oxygen results from the horses remain stable along each tooth. This pattern points to consistent feeding and watering during growth. The animals relied on C3 plants such as temperate grasses and likely received additional fodder. Oxygen values suggest access to steady water sources such as rivers or wells rather than seasonal ponds. Genetic work shows that the sacrificed horses were males between five and seven years old, an age linked with their physical prime.

One equid stands apart. A donkey shows strong shifts in strontium along the tooth, which signals movement across different geological zones early in life. Carbon and oxygen values also vary more than in the horses. Such a profile fits an animal used for transport rather than managed in a single, controlled setting.

Cattle and sheep or goats present a different picture. Their strontium ratios often match the local baseline, which suggests a nearby origin. Carbon and oxygen values vary more than in horses, which reflects flexible grazing and water use on floodplains and surrounding fields. Some caprines show limited movement during life, providing early isotopic evidence for small-scale mobility of sheep or goats in this region.

The combined data show careful planning behind the final ceremony at Casas del Turuñuelo. Organizers gathered high-value horses raised in specific parts of the Guadiana basin while also using locally managed cattle and caprines for the banquet. The selection of animals, their ages, and their origins point to coordinated networks and deliberate management rather than a single local herd.

This study offers the most detailed isotopic investigation so far of equid management in southwestern Iberia during the Iron Age. The findings connect animal husbandry, exchange, and ritual practice at a moment when the Tartessian building was closed and buried.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.