Anyone who has stood near an ancient Egyptian mummy notices a persistent musty odor. Researchers once linked this smell to age and decay. New chemical work shows a different cause. The odor forms from a complex mix of volatile organic compounds released by embalming materials and preserved tissues. These compounds record details about balm ingredients and changes in mummification practices over time.

A research team from the University of Bristol analyzed air surrounding Egyptian mummies instead of removing physical samples. Traditional chemical studies often require cutting bandages or dissolving material, a process that damages fragile remains. The Bristol approach relies on headspace solid phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry. This method captures gases present above mummified bodies and storage containers, then separates and identifies individual molecules.

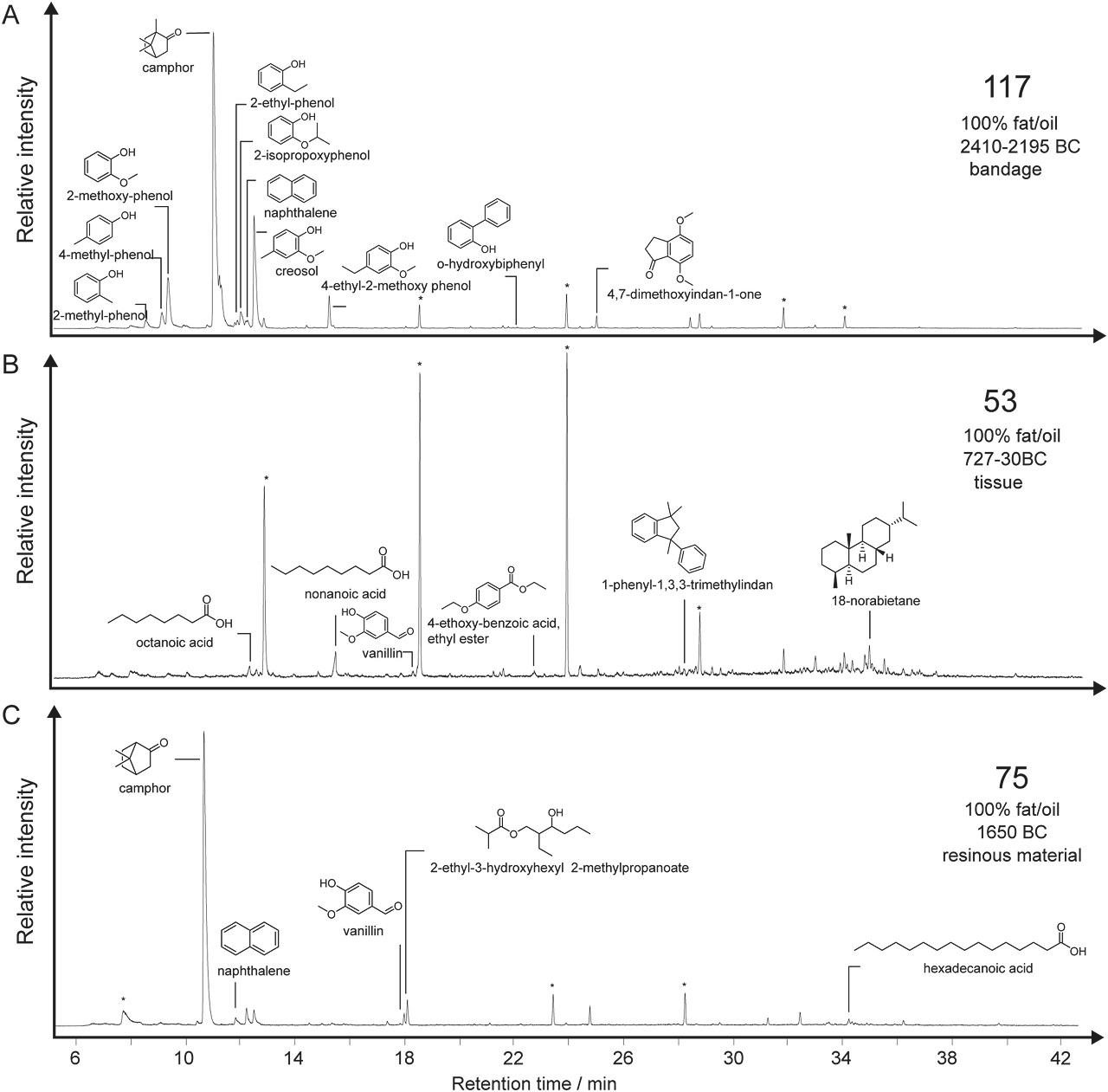

The study examined 35 samples of balms and bandages taken from 19 mummies spanning more than 2,000 years of Egyptian history. Across all samples, researchers identified 81 distinct volatile organic compounds. These compounds grouped into four main categories linked to embalming substances. Fats and oils produced aromatic compounds and short-chain fatty acids. Beeswax contributed mono-carboxylic fatty acids and cinnamic compounds. Plant resins released aromatic compounds and sesquiterpenoids. Bitumen produced naphthenic compounds, even when present in very small amounts.

Chemical patterns varied across historical periods. Earlier mummies showed simpler profiles dominated by fats and oils. Later mummies displayed more complex mixtures that included imported resins and bitumen, materials associated with higher cost and specialized preparation. Volatile profiles also differed between body regions. Samples from heads often contained different compound patterns than samples from torsos, suggesting embalmers applied distinct recipes to separate parts of the body.

The findings, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, demonstrate a close link between volatile profiles and known balm compositions. Volatile analysis also proved sensitive enough to detect bitumen markers present at extremely low mass fractions, a task difficult with earlier methods focused only on soluble residues.

This approach expands the study of ancient Egyptian funerary practices by adding a sensory and chemical dimension. By pairing volatile data with earlier analyses of solid balm components, researchers gain a more complete view of mummification recipes, material choices, and preservation strategies. Museums and collections benefit as well. Air sampling offers a rapid, non-destructive screening tool for fragile mummies, allowing curators to gather chemical information while preserving physical integrity. Physical sampling still plays a role for detailed work, yet volatile analysis provides an effective first step for studying embalmed remains across collections and time periods.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.