Research conducted by scholars from the University of Tübingen challenges long-standing assumptions regarding the origins of human culture through stone tools.

Stone tools unearthed through archaeological excavations, some dating back as far as 2.6 million years, have been regarded as evidence of early cultural development in human evolution.

However, Dr. Claudio Tennie and William Snyder from the Department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology at the University of Tübingen have undertaken a study, supported by the European Research Council, that questions this conventional interpretation.

Through experimental investigations, they have arrived at a different conclusion: the earliest techniques for crafting stone tools can be spontaneously reinvented without the need for cultural transmission.

Consequently, these tools do not necessarily indicate the emergence of human culture, which might have potentially commenced at a later stage, as suggested by the researchers. The study has been published in Science Advances.

Tools made from scratch

In this experiment, the researchers recruited 28 local adults who were not experts in archaeology. These participants were given a task to open a box that contained monetary rewards.

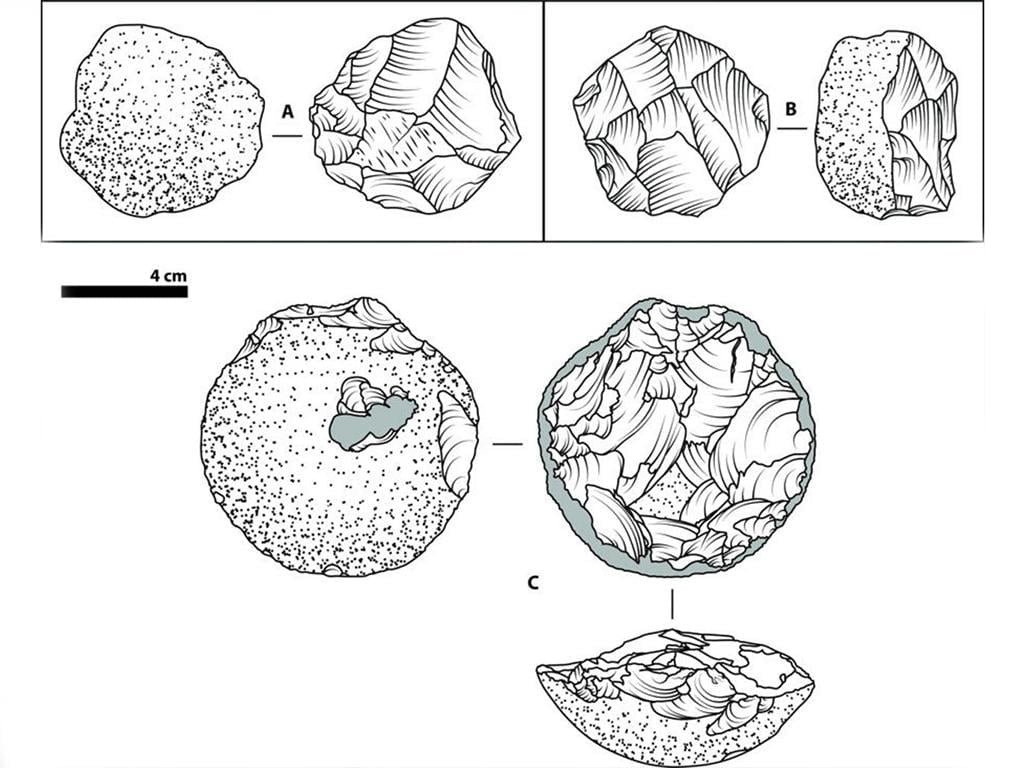

They were provided with raw materials including a painted glass hemisphere, a medium-sized river pebble, and a large granite block.

The participants were given complete freedom to use these materials in any way they saw fit to break a rope that secured the box. They received no prior information or demonstrations about the techniques used in early stone tool production.

Through post-test questionnaires, it was determined that 25 participants had no prior knowledge of early stone tool production techniques at the beginning of the test. Despite their lack of knowledge, the majority of participants demonstrated innovation by developing at least one of these techniques and effectively used the resulting tools to cut the rope and open the puzzle box.

The authors observed that all the production techniques of early stone tools were spontaneously re-invented by the participants, even without prior knowledge, thus highlighting their capacity for on-the-spot innovation.

According to Claudio Tennie, these findings challenge previous assertions that the process of learning to make stone tools must inherently be difficult and impossible without models to imitate.

Tennie states, “If the earliest stone tools in the human record really had been the first cases of human culture, then they should resist spontaneous innovation – they should not come about anew ‘from scratch’, in the absence of cultural transmission.”

Prior to revealing their results, Tennie mentions that when discussing this matter with other researchers, most did not anticipate this outcome. The prevailing belief was that all stone tool production required copying, which this study disproves.

William Snyder summarizes that the existence of stone tools 2.6 million years ago can no longer be considered definitive evidence that our early Stone Age ancestors possessed culture similar to our own. “We must now look at much later time periods for the origin of modern human culture.”

Publication: William D. Snyder et al, (2022), Early knapping techniques do not necessitate cultural transmission, Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abo2894