A strip of land along England’s west coast, now known for its picturesque beaches, was once a bustling highway for both ancient humans and animals. Today, the ebb and flow of the tide reveal an astonishing history of footprints left by these travelers thousands of years ago.

Located near Formby, England, this coastline stretches for nearly 2 miles and is home to one of the world’s largest concentrations of prehistoric Holocene vertebrate traces. While footprints from the past have been found across the globe, the Formby footprint beds hold a special place in the annals of ancient history.

The story of these footprints began in the 1970s when they were first discovered, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that their true significance became apparent. A retired teacher recognized their antiquity, sparking interest among archaeologists. Alison Burns, an archaeologist at The University of Manchester, described this shift, stating, “Before then, people didn’t think the prints were particularly interesting or old.”

In a groundbreaking study, researchers have now dated these footprints, revealing a timeline that spans more than 8,000 years, from the Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age (15,000 BCE to 50 BCE) to the Middle Ages (476 to 1450 CE). The dating process involved collecting seeds from alder, birch, and spruce trees found along the route and using radiocarbon dating techniques to determine the age of the tracks.

These well-preserved footprint beds, totaling around a dozen, are often layered upon each other, creating approximately 36 exposed strata or “outcrops.” Within these layers, a diverse collection of footprints can be found, not only of humans but also of various animals, including aurochs (an extinct ox species), deer, wild boar, wolves, lynxes, and cranes.

Alison Burns explained that only some of these outcrops are visible at any given time. She added, “The farther down you dig, the older the outcroppings are.”

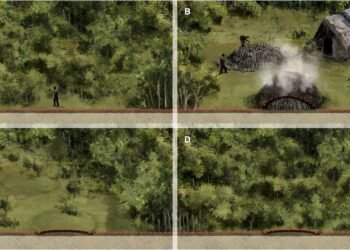

The oldest beds, located toward the south of Formby Point, date back to approximately 8,000 years ago. These footprints provide a unique glimpse into the movement patterns of both humans and animals as they adapted to shifting shorelines following the last ice age, which occurred between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago. Alongside human footprints, traces of other large mammals, such as aurochs, red deer, roe deer, wild boar, and beavers, were found, as well as evidence of predators like wolves and lynxes.

The preservation of these footprints beneath the sand, protected by layers of mud, is gradually being eroded as the shoreline shifts. As the team uncovered more layers, they discovered a particularly intriguing set of footprints dating back around 8,500 years.

This set of human footprints, characterized by the swelling of mud between each toe, paints a vivid picture of a barefoot individual who paused after taking four or five steps. The context of these footprints reveals a narrative of hunting; right beside the human footprints are those of a crane, suggesting the person may have been on a scouting expedition in search of birds to hunt. Additionally, a series of adult deer tracks is found nearby, providing a snapshot of ancient life within a compact 22-square-foot area.

Alison Burns emphasized the importance of considering animal footprints in addition to human ones, saying, “Many footprint studies typically focus on the human prints and not the animal prints. I was really interested in seeing how the animals and humans shared this very populated environment.”

This study not only contributes to our understanding of ancient human and animal behavior but also has broader implications for our understanding of sea-level rise and its impact on coastal regions and ecosystems. It serves as a reminder that the boundaries between land and sea have always been dynamic, with ancient travelers adapting to changing landscapes over thousands of years.

(This article is based on reports from Live Science and The Weather Channel.)