In the late 1990s, a trio of Islamic glass fragments was unearthed by archaeologists at Caerlaverock Castle near Dumfries, Scotland.

These fragments have inspired a collaborative community project called Eternal Connections, aimed at understanding their origins and reconstructing the original object—a medieval Islamic glass drinking beaker. The inscriptions on the fragments, part of the Arabic word for “eternal,” suggest a connection to one of Allah’s 99 names, possibly from the Qur’an.

Despite their small size, these fragments provide valuable clues about Scotland’s interactions with the wider world during the medieval period.

During medieval times, glass was primarily used for stained glass windows in religious buildings such as monasteries, cathedrals, and some smaller churches and chapels in Scotland. However, its use in castles and tower houses did not become common until centuries later.

Glass items were rare in this region and often degraded due to Scotland’s acidic soil. Nearly a quarter-century after their discovery, these fragments have been thrust into the spotlight by the Eternal Connections project, igniting discussions and learning about Scotland’s Muslim communities.

Eternal Connections leverages cutting-edge scientific analysis and research data to gain a deeper understanding of Scotland’s contemporary and historical connections. Stefan Sagrott, an Archaeologist and Senior Cultural Resources Advisor from Historic Environment Scotland (HES), expressed astonishment at the discovery of Islamic glass from the 13th century in a Scottish castle.

Glass was not commonly used during this period, making the find even more remarkable. Glass items from that time, especially those used as window glass in castles, are scarce due to their vulnerability to degradation in acidic soil.

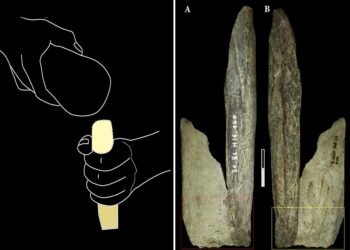

Alice Martin, a visual artist from Stirlingshire, played a pivotal role in the project. She conducted research on contemporaneous medieval Islamic glass and collaborated with a team of HES experts who employed state-of-the-art techniques to analyze the fragments and generate 3D data.

Using this data, Martin created a 3D-model digital reconstruction of the glass fragments, offering a glimpse of what the beaker might have looked like originally. The reconstructed beaker features a vase shape with a blue and gold line below the rim adorned with Arabic writing and a golden fish.

The fragments are adorned with an Arabic inscription that would have encircled the beaker when it was complete. Scientific analysis indicated the presence of red and gold decorations, in addition to the visible blue and white designs.

This type of Islamic glass was considered valuable for its precision and delicate craftsmanship. The researchers thoroughly explored how an Islamic glass drinking beaker ended up in Scotland, considering scientific data, research, and known history.

It is suspected that the beaker may have reached Caerlaverock Castle through trade or could have been brought back by returning crusaders.

The Eternal Connections project extended its scope to include community engagement. It collaborated with various groups, including the Muslim Scouts in Edinburgh and AMINA – Muslim Women’s Resource Centre in Glasgow, to organize informative workshops focused on the story of the Islamic glass.

These workshops delved into the beaker’s shape, decorative designs, and calligraphy using Arabic script and Gaelic. Additionally, participants explored archaeology and the technology used to analyze the glass fragments.

The impact of Eternal Connections on the community, particularly the participants from AMINA, exceeded expectations. The small glass fragments held themes of separation, uncertainty, homeland, and family, resonating with the group’s experiences.

Many women in the group faced challenges participating in society due to the UK asylum system, making the opportunity to share their extensive knowledge about history and culture with the HES team highly significant.

Dr. Lyn Wilson, HES’s Head of Programme for Research and Climate Change, lauded the project’s success in unraveling the story behind the three glass fragments and reconstructing a replica of the medieval Islamic glass drinking beaker. — Historic Environment Scotland (HES)