Analysis of stone tools attributed to the Ahmarian, the Near East’s first Upper Paleolithic culture (about 40,000 to 45,000 years ago), reveals that small, elongated, symmetrical items (bladelets) were mass-produced on-site. Such standardized production is consistent with what archaeologists have previously suggested is linked with the introduction of the bow and arrow.

The most typical Ahmarian tool is the el-Wad point, a flint blade or bladelet with an additional, intentional modification, a so-called retouch. They are a common variant of shaped spear or arrow tips from the early Upper Paleolithic. According to the new findings, el-Wad points in Al-Ansab are the result of attempts to reshape bigger, asymmetrical bladelet artifacts to reach quality standards of the unmodified bladelets, which are small, elongated, and symmetrical.

This is the main result of the research carried out by Jacopo Gennai, Marcel Schemmel, and Professor Dr. Jürgen Richter (Department of Prehistoric Archaeology, University of Cologne). According to the authors, the southern Ahmarian had already completed the technological and cultural shift to the preferred usage of small bladelets, used as spear or even arrow tips. The article has now been published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology.

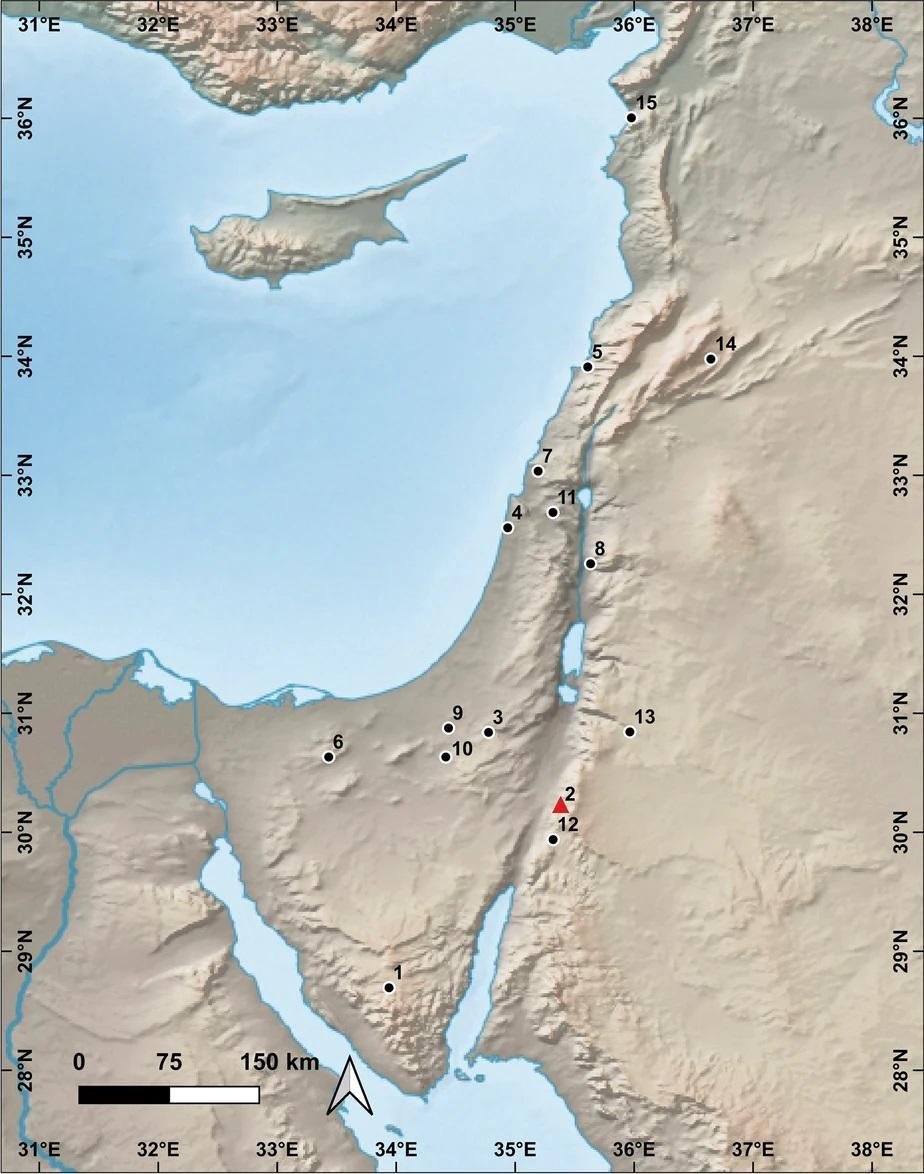

Since 2009, a team from the University of Cologne led by Jürgen Richter has been excavating at Al-Ansab 1, which is located approximately 10 kilometers south of the well-known ruin city of Petra in Jordan. The site is significant as it is one of the best-preserved pieces of evidence of the Ahmarian technocomplex recorded in an open-air context.

Jacopo Gennai, the lead author, re-analyzed a representative part of the excavated material from 2018 to 2021 to better understand how the production methods of similar bladelets were within the extent of the early Upper Paleolithic.. Moreover, a student member of Richter’s team, Marcel Schemmel, produced a new analysis of the el-Wad point, constraining its definition to more precise typo-metrical criteria.

The early Upper Paleolithic is identified as the cultural marker of our species’ final successful push into Eurasia. Small, slender, and highly standardized bladelets are likely to be the remains of arrows or throwing spears used to catch ungulates in open steppe environments of the time. Bladelets then show the start of long-range hunting, which is a significant departure from previous hunting practices.

The new findings reveal that, rather than being mere residual products, the little bladelets were central to Homo sapiens’ success during the Upper Paleolithic.Being standardized and disposable, this flexible technology likely facilitated the successful dispersal of our species throughout Europe, allowing groups to cover great distances in unknown territories without needing to rely on sources of big, good-quality raw materials.

“During the Upper Paleolithic, we have a proliferation of bladelets, but their role was not well established yet within the Ahmarian. We hope these new results will change our understanding of the earliest Upper Paleolithic industry of the Levant and push for new research to find the origins of this behavior that stayed with Homo sapiens until the end of the Paleolithic,” Dr. Gennai stated.

More information: Jacopo Gennai et al, (2023). Pointing to the Ahmarian. Lithic Technology and the El-Wad Points of Al-Ansab 1, Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology. DOI: 10.1007/s41982-022-00131-x