Te’omim Cave, nestled in the Jerusalem Hills east of Beit Shemesh, Israel, has long been a place of intrigue and myth. Local oral tradition has attributed magical healing and fertility powers to its spring waters, based on a legend from the 19th century.

Recent excavations between 2010 and 2016 have shed light on the cave’s hidden past, revealing a treasure trove of artifacts that hint at its enigmatic history during the Late Roman period.

An article published in the Harvard Theological Review by researchers Eitan Klein from the Israel Antiquities Authority and Boaz Zissu from Bar-Ilan University presents compelling evidence that Te’omim Cave once hosted an esoteric religious cult engaged in ritual practices, possibly involving necromancy and communication with the dead.

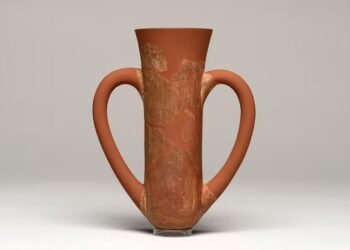

The discoveries include over 120 well-preserved Roman oil lamps, strategically placed in narrow crevices and hidden beneath rubble within the cave.

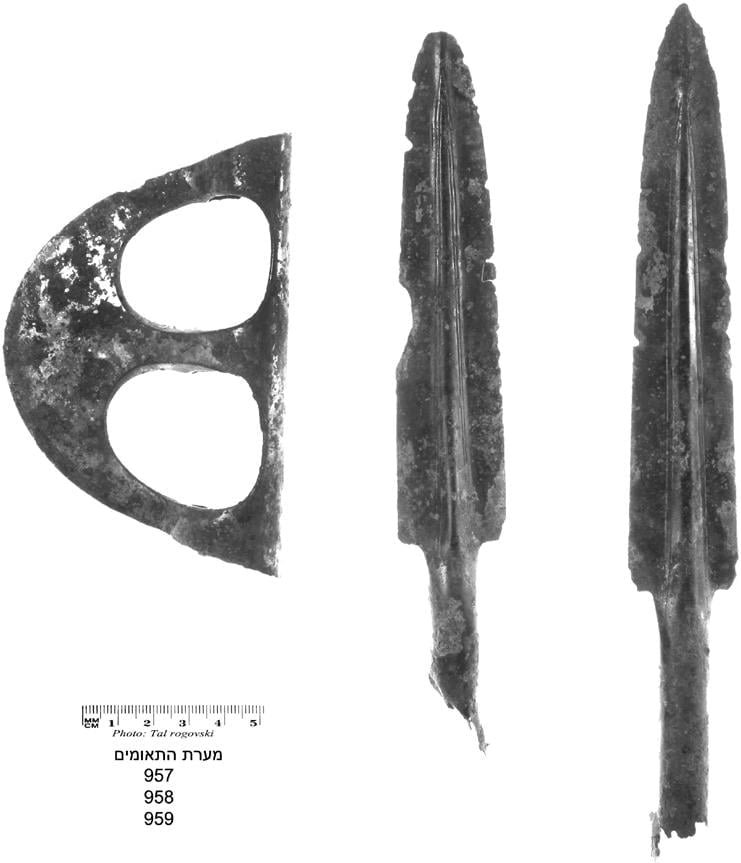

Alongside these oil lamps were weapons, such as daggers and axe heads, as well as three human skulls. The deliberate concealment of these artifacts suggests that the lamps served a greater purpose than merely illuminating the darkness.

The researchers propose that these artifacts were essential components of necromancy ceremonies held in the cave during the Late Roman period. Necromancy, the act of conjuring the spirits of the dead to predict the future and communicate with the other realm, was a common form of divination and magic in ancient times.

The cultic site of Te’omim Cave may have served as a portal to the underworld, making it a suitable location for such practices.

One particular spell discovered in the region details how to raise the spirit of the dead using a disinterred skull, while another uses a skull to seek assistance and protection from spirits.

Oil lamps were believed to have prophetic powers, and messages were sought through interpreting the shapes created by the flame. These lamps were likely used to lure spirits to the realm of the living during rituals conducted in the cave.

Additionally, the presence of weapons in the cave, such as daggers, was not indicative of live sacrifices but instead served as protective talismans against malevolent spirits. It was believed that evil spirits feared metal, especially iron, and bronze, so keeping a metal weapon close by offered some defense.

The study speculates that the cultic practices in Te’omim Cave were primarily conducted by non-Jewish residents of the area, given its location in a region densely populated by gentiles during the Late Roman period.

While the exact purpose of the human skulls remains uncertain, the evidence from this cave is consistent with practices seen throughout the Roman Empire. Necromancy and communication with the dead were widespread, and artifacts like human skulls were commonly employed in such rituals.

The significance of Te’omim Cave as a local oracle (nekyomanteion) adds to the emerging field of the “archaeology of magic.” The findings provide valuable insights into divination rites conducted during ancient times and offer a tangible connection to the magical practices documented in the Greek and Demotic Magical Papyri.