A team of paleontologists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, working in collaboration with Xi’an Jiaotong University, the University of York, the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the National Research Center on Human Evolution, has found evidence of a previously undocumented human lineage.

The research, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, centered around the analysis of fossilized remains—a jawbone, partial skull, and leg bones—dating back 300,000 years.

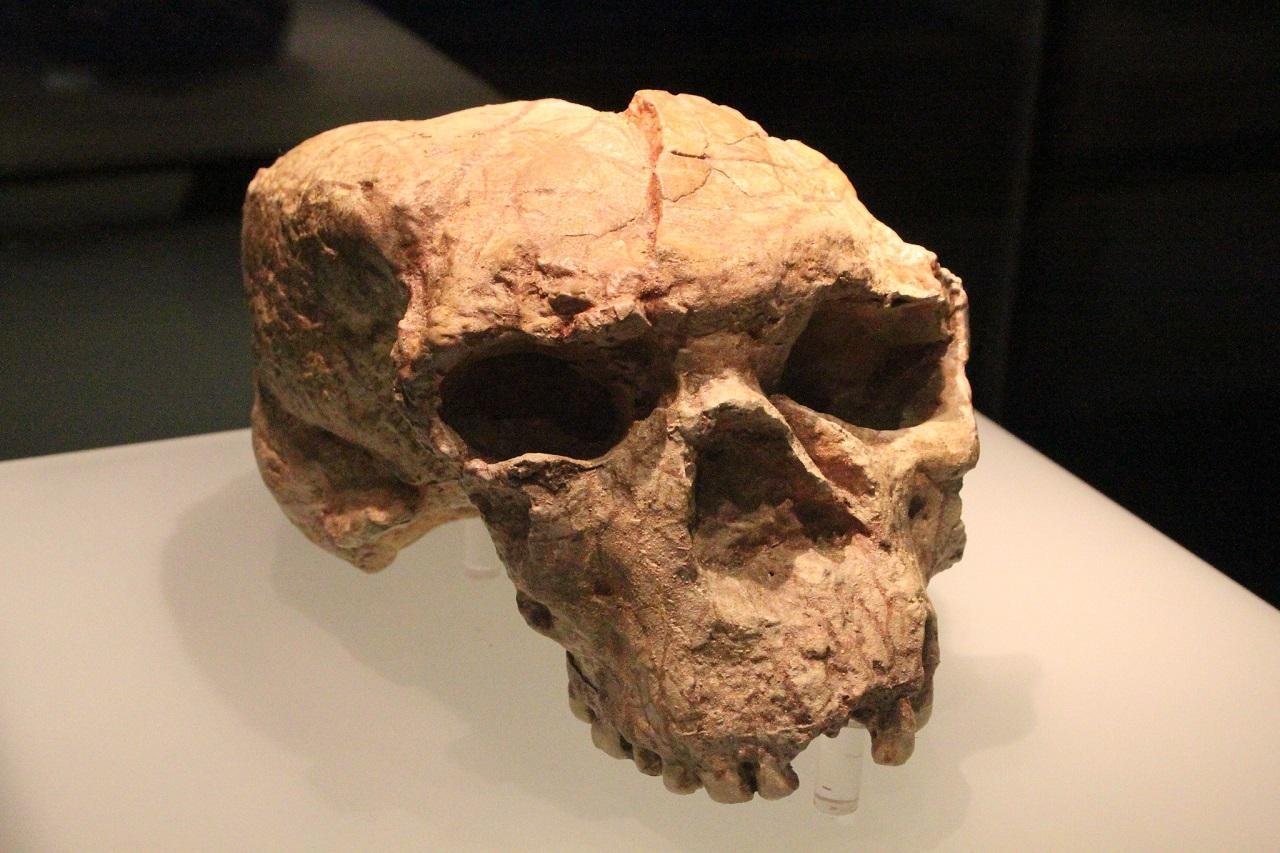

Excavated in Hualongdong, an area that is now part of East China, these fossils were subjected to both morphological and geometric scrutiny. The focal point of analysis was the jawbone, displaying distinctive traits such as a triangular lower edge and an unprecedented bend, setting it apart from other hominids.

Credit: Gary Todd/Flickr (Public Domain)

The absence of a chin in the jawbone’s structure indicated a connection to older species, while other features were reminiscent of Middle Pleistocene hominins, particularly Homo erectus.

Moving from the jawbone to the skull, the scientists made another intriguing observation. This skull, initially identified as the oldest Middle Pleistocene human skull in southeastern China, demonstrated facial similarities to modern humans rather than the attributes displayed by the jawbone.

This mosaic pattern—reflecting both ancient and modern traits—led the researchers to suggest the possibility of a hybrid between modern humans and ancient hominids. The findings suggest a connection between shared traits and the appearance of modern human characteristics dating back 300,000 years ago.

Efforts to classify the remains led to the elimination of the Denisovan lineage, narrowing the possibilities down to a new lineage—one potentially bridging modern humans and other ancient hominins in the region, such as Denisovans.

This revelation challenges the established narrative of human evolution, indicating the coexistence of three lineages in Asia: Homo erectus, Denisovans, and this newly discovered lineage, which possesses significant phylogenetic proximity to Homo sapiens.

While the emergence of Homo sapiens in China was only documented around 120,000 years ago, the presence of modern features in the newly discovered remains raises the possibility of their manifestation much earlier.

This revelation isn’t the first to complicate the linear trajectory of human evolution. Previous discoveries of ancient human remains in different parts of the world have revealed a tapestry of features that challenge simplistic models. Rather than a direct line from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens, the complexity of archaic Homo sapien fossils suggests a more intricate evolutionary web.

The uncovered skull, believed to belong to a child aged 12 or 13, encapsulates this complexity. This amalgamation of features is unprecedented in late Middle Pleistocene hominids in East Asia, sparking discussions about the potential need for a revised human family tree.