In a study led by Complutense University, Madrid, researchers have unveiled a remarkable array of ancient cave paintings.

The study, recently published in Antiquity, employs innovative digital stereoscopic recording techniques to explore the depths of La Pasiega cave’s rock art, a site previously thought to be thoroughly examined.

Through these techniques, the scientists uncovered previously unnoticed animal figures intricately intertwined with the existing cave art. Among their discoveries were depictions of horses, deer, and a large bovid, possibly an aurochs, all of which had remained concealed until now.

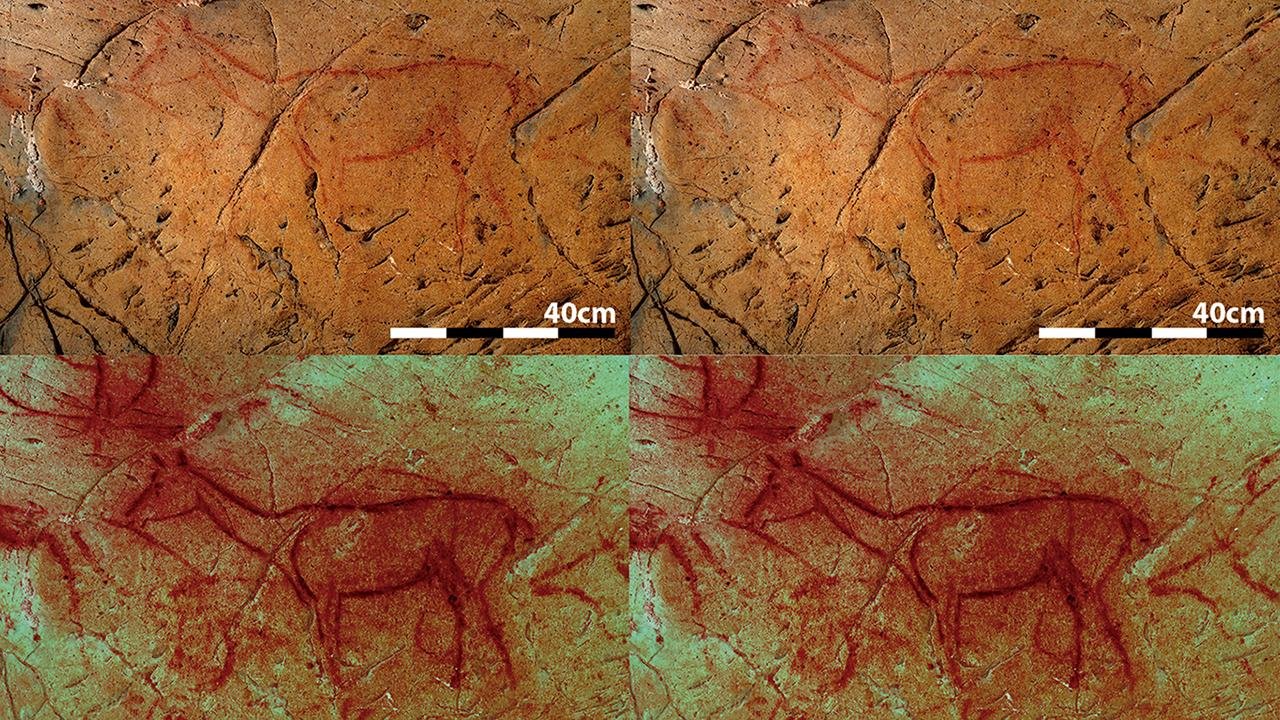

Many of the figures, which had previously been considered incomplete, suggesting that the artists abandoned their work prematurely, were reinterpreted as fully realized animal representations thanks to stereoscopic photography and a more profound understanding of how natural rock formations were incorporated into the artworks.

Stereoscopic photographs allowed the researchers to establish connections between the images and the irregularities present in the cave’s rock walls. These connections, often invisible in traditional two-dimensional photographs, provided vital information about the artists’ intentions and methods.

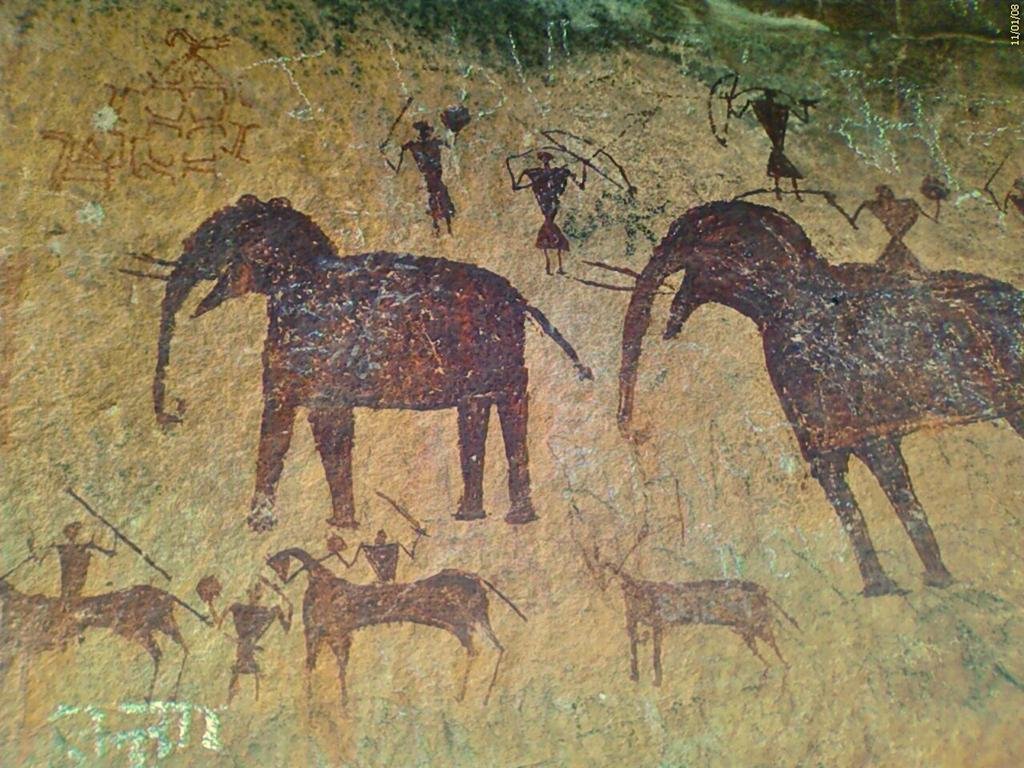

One of the most intriguing aspects of this study is how the ancient artists ingeniously incorporated the cave’s natural features into their depictions. They effectively merged the man-made and the natural, creating a harmonious interaction that infused depth and three-dimensionality into the artwork.

This innovative technique suggests that the topographical features of the cave walls may have inspired the artists’ imaginations. In a psychological phenomenon known as pareidolia, they may have seen unintended forms in nature, much like modern-day cloud-watching.

For instance, a recently discovered horse image, approximately 460 x 300mm in size and painted in red using variably spaced dots, showcases the head, corner of the mouth, eye, ear, and the beginning of the cervico-dorsal line. This figure cleverly incorporates the natural features of the cave wall, with the rock’s cracks merging seamlessly into the outlines of the head and chest. The cervical-dorsal line conforms to a concave area of the wall.

Another horse, painted in yellow ochre and measuring 600mm from head to hindquarters, highlights the head, mane, back, and hindquarters as the previously identified painted anatomical parts. The authors suggest that a rock edge delineates the horse’s belly, with the natural rock cracks defining the foreleg, even without paint.

This research revealed numerous connections between the images and the cave wall’s irregularities, a feature often overlooked in past studies that primarily relied on color, form, and painting or engraving techniques.

The study’s findings underscore the importance of considering both the artistic renderings and the topographical features of the cave’s rock surface when analyzing Paleolithic rock art.