In a new study led by William Taylor, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder, in collaboration with researchers from Argentina, new insights have emerged regarding the transformative effects of domestic horses on Indigenous societies in southern Argentina.

The study focused on the archaeological site of Chorrillo Grande 1 in Patagonia, Argentina, where Juan Bautista Belardi, a professor of archaeology at the Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia Austral, and his team conducted extensive field research. Unearthing the remains of an Aónikenk/Tehuelche campsite, the researchers discovered horse bones, artifacts, and metal ornaments, providing crucial evidence of the profound impact horses had on the local way of life.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the findings suggest that the integration of horses into Indigenous societies in the region predates European colonization by over a century. DNA sequencing, radiocarbon dating, and isotope analysis conducted by Taylor and his colleagues revealed the life history of the horses, demonstrating their mobility between valleys and reshaping the landscape of the ancient world.

The study indicates that horses catalyzed rapid economic and social transformations, influencing various aspects of daily life, including hunting, transportation, and social organization.

“The advantages clearly showed up as soon as people had horses—the chance to save energy riding them, to extend the radius of hunting parties, less time needed to find prey and the ease to transport things, among others,” said Belardi. The transformative impact of horses on the Indigenous Tehuelche nation’s lifestyle was extensive, affecting not only their economic activities but also social and ideological aspects.

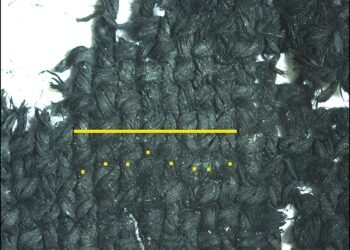

The Chorrillo Grande 1 site provided evidence of the pastoral management of horses by Aónikenk/Tehuelche hunter-gatherers, with DNA-based sex identifications suggesting the consumption of both male and female horses. The archaeological record also revealed the processing of ruminant carcass fats, potentially from guanaco, illustrating the diverse uses of horses in their lifeways.

The integration of horses into Indigenous cultures in southern Argentina contradicts historical records that insufficiently capture the intricacies of this introduction. The study proposes that the spread of horses was rapid and largely mediated by Indigenous communities, challenging the Eurocentric perspective often present in historical accounts.

Taylor’s research contributes to a broader understanding of the “human-horse story,” a topic he delves into in his upcoming book, “Hoof Beats: How Horses Shaped Human History,” set to be published by the University of California Press later this year. Reflecting on the ongoing impact of horses, Taylor remarked, “Even in 2023, these roles and impacts are still visible just under the surface of the world around us.”

The study not only highlights the transformative role of horses in shaping life in Patagonia but also sets the stage for further research. Taylor expressed the research team’s hope to continue exploring the role of horses in ancient Argentina and South America, connecting their findings with research in other parts of the ancient world.