The remnants of a Bronze Age tomb, believed to have been lost to history in the mid-19th century, have been rediscovered in County Kerry on the Atlantic coast of Ireland.

The megalithic structure, known as Altóir na Gréine or the Sun Altar, dates back approximately 4,000 years and was thought to have been destroyed in the mid-19th century when locals reportedly dismantled it for building materials.

The tomb gained prominence in the 19th century when Lady Georgiana Chatterton, an English aristocrat and traveler, visited the site in 1838. She sketched the monument, describing it as a “curious piece of antiquity” believed to have been used for offering sacrifices to the sun. However, by 1852, antiquarian Richard Hitchcock reported that the tomb had been broken up and used for building purposes, leading to its apparent disappearance.

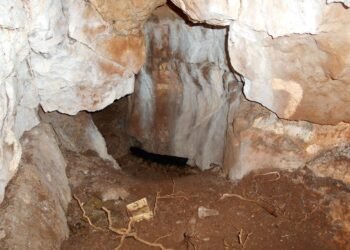

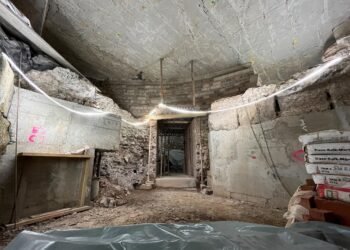

The recent rediscovery was made by local folklorist Billy Mag Fhloinn, who, as part of an archaeological mapping project, stumbled upon stones on the crest of a hill matching Lady Chatterton’s sketch. Mag Fhloinn’s careful examination revealed several large upright stones, called orthostats, and a capstone, comprising about a quarter of the original tomb. This finding challenges the belief that the tomb had been entirely destroyed, as previously assumed.

Mag Fhloinn said: “People had assumed it was all destroyed.” He converted his discovery into a 3D scan and sent the material to the National Monuments Service in Dublin. Archaeologist Caimin O’Brien confirmed that the stones belonged to a wedge tomb from the early Bronze Age, dating between 2500 BCE and 2000 BCE.

Wedge tombs, like Altóir na Gréine, are common megalithic burial structures in Ireland, often positioned on high ground with specific alignments. They are associated with the Bronze Age practice of interring bodies and conducting ceremonies. The newly rediscovered tomb’s apparent northwest/southeast orientation raises questions about possible alignments with the sun.

The significance of this rediscovery extends beyond the local community, as the tomb will now be added to the database of national monuments.

“For the first time in over 180 years, archaeologists know where the tomb is situated, and it will enhance our understanding of wedge tomb distribution,” archaeologist Caimin O’Brien told RTÉ. This rediscovered tomb will also become part of a deep-mapping project conducted by Sacred Heart University, a US institution recording burial tombs on the Dingle Peninsula and creating 3D models for further analysis.

Tony Bergin, president of the Kerry Archaeological and Historical Society, mentioned a theory linking this specific type of tomb to a people involved in copper mining, drawing comparisons to similar tombs found in Brittany, France.

Despite the newfound clarity on the tomb’s location, questions about its original destruction in the 19th century persist. Folklorist Mag Fhloinn speculates on the taboo surrounding the destruction of such sites during that period, suggesting beliefs in bad luck or disaster associated with their demise.