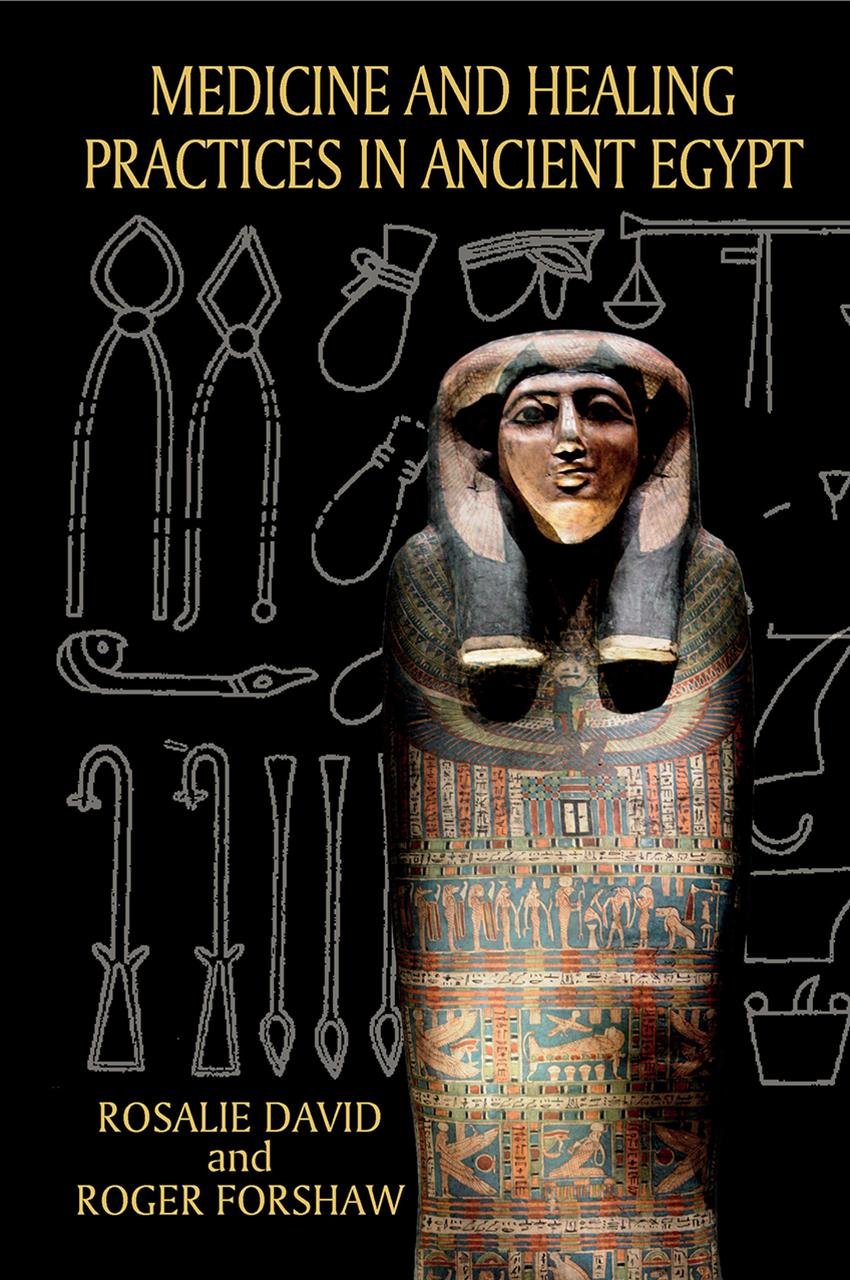

Ancient Egypt’s healthcare system, described as “advanced and successful” by researchers Rosalie David and Roger Forshaw in their new book, “Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt,” offers a unique perspective on the practices that thrived in the land of the pharaohs over three millennia.

Affiliated with the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, the authors present a “people-focused” interpretation, shedding light on the interaction between healthcare providers and their patients.

Affiliated with the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, the authors present a “people-focused” interpretation, shedding light on the interaction between healthcare providers and their patients.

The comprehensive study delves into the intricacies of ancient Egyptian medicine, highlighting pharmaceutical treatments involving minerals, plant ingredients, and animal parts. Basic surgeries, pragmatic remedies like bandaging broken limbs, and, to a lesser extent, “magical” treatments were universally available across all societal levels.

Professor Rosalie David, an emeritus professor of biomedical Egyptology, says: “The Egyptian healthcare system was advanced and successful, not least for devising innovative ways to treat snake bites and save lives.” The researchers point out that despite the absence of a complete picture of ancient Egyptian life, evidence suggests that individuals had some autonomy in choosing their healthcare providers.

Inscriptions reveal the dual religious and secular roles of physicians, who not only provided medical treatment but also served as priests in healing-associated deities’ temples. Payment for care was likely based on affordability, making treatments accessible beyond the affluent class. Physicians and health workers, including midwives, visited patients’ homes, while temple precincts provided centralized locations for treatments and therapy.

The ancient Egyptians did not categorize diseases; instead, their medical documents focused on individual case studies, listing symptoms and potential outcomes. Infectious diseases were sometimes attributed to deities or perceived enemies, requiring prayers, rituals, or “magical” treatments. Mental illnesses were recorded based on symptoms rather than specific diseases.

Notably, the ancient Egyptians displayed an enlightened attitude toward deformities and disabilities, unlike their Greek counterparts. Individuals with disabilities were not excluded from working in temples, and specific careers were designated to provide livelihoods for diverse groups. This progressive approach extended to old age, where cosmetic treatments were used to combat the appearance of aging.

Addressing the prevalence of snake and scorpion bites, the researchers highlight the Brooklyn Papyrus, dating back to around 450 BCE, as one of the oldest writings about medicine. The document outlines various snakes, their habitats, symptoms of bites, and deity associations, offering treatments ranging from practical interventions to magical incantations. The use of natron, a naturally occurring compound, showcased the Egyptians’ practical knowledge in treating such ailments.

Despite an average life expectancy similar to other ancient societies, approximately 90 percent of the adult population in ancient Egypt did not live beyond the age of fifty. Notable exceptions, like Pharaoh Ramesses II, underscored the rarity of individuals reaching old age.

The enduring legacy of ancient Egyptian healthcare is evident in various aspects of modern Western medicine. Techniques for treating dislocated jaws, recorded in the Edwin Smith Papyrus around 1600 BCE, remain in use. The Egyptians’ pioneering use of sutures and medical instruments like scalpels is also acknowledged.

While surgical treatments were limited, evidence from medical papyri, such as the Ebers Papyrus, detailed surgical procedures like incisions for swellings. Bandages and wound coverings made of linen were common, showcasing early wound management practices. The Ebers Papyrus also discusses medicinal formulations for treating burns.

The researchers underscore that despite appearing unsophisticated by twenty-first-century standards, ancient Egyptian medicine demonstrated evidence-based practices four millennia ago. The centrality of the patient’s role and the enlightened attitude toward deformities and disabilities constitute the Egyptians’ enduring legacy to the modern world.