Archaeologists from Newcastle University, in collaboration with experts from the University of Sheffield, have recently conducted excavations near Crowland, Lincolnshire, unearthing a remarkable and multifaceted sacred landscape that spans centuries.

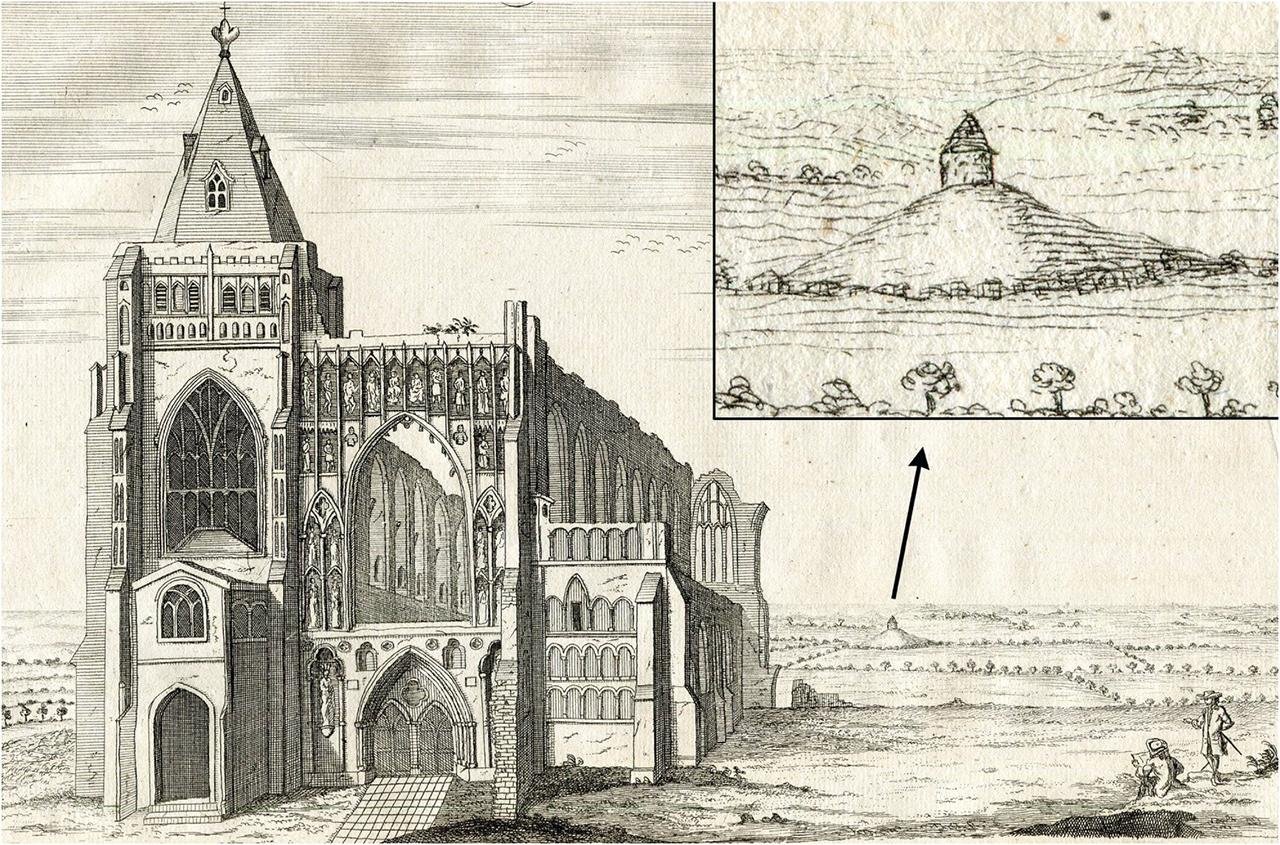

At the heart of this exploration lies the search for the hermitage of Saint Guthlac, a revered figure in local folklore and early Christian history. Saint Guthlac, known for his ascetic lifestyle and renunciation of wealth as a nobleman’s son, established his hermitage in the early 8th century on what was believed to be a previously looted burial mound. This site, steeped in legend and documented in the Vita Sancti Guthlaci, written by the monk Felix shortly after Guthlac’s death, attracted pilgrims and eventually led to the founding of Crowland Abbey in the 10th century.

For years, the exact location of Guthlac’s hermitage remained a mystery, with Anchor Church Field often considered a likely candidate. However, extensive excavation in this area has been hindered by agricultural activity until recent years.

Surprisingly, the archaeological team’s findings surpassed expectations. They unearthed a previously unknown Late Neolithic or early Bronze Age henge, one of the largest ever discovered in eastern England. This circular earthwork, strategically positioned on a peninsula amid marshes and waterways, would have been a prominent feature of the landscape, serving as a focal point for ceremonial activities.

The henge, later reoccupied during Guthlac’s era, yielded artifacts such as pottery, bone combs, and fragments of high-status drinking vessels from the Anglo-Saxon period. Dr. Duncan Wright, Lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at Newcastle University, “We know that many prehistoric monuments were reused by the Anglo-Saxons, but to find a henge—especially one that was previously unknown—occupied in this way is really quite rare.”

Furthermore, the excavation uncovered remnants of a 12th-century hall and chapel, likely constructed by the Abbots of Crowland to honor Saint Pega, Guthlac’s sister, who was also a hermit of note in the region. This complex would have provided accommodations for high-status pilgrims visiting Crowland, further solidifying the site’s importance as a religious center. A significant discovery near the 12th-century hall—a stone-lined pit thought to be a well—may have served as the setting for a large cross.

As the centuries passed, the landscape of Crowland underwent transformations, with the draining of marshlands and conversion to farmland altering the topography. Despite these changes, the site retained its sacred significance, as evidenced by historical records of continued veneration well into the 18th century.

Dr. Hugh Willmott from the University of Sheffield emphasized, “By examining the archaeological evidence we uncovered and looking at historic texts, it’s clear that even in later years Anchor Church Field continued to be seen as a special place worthy of veneration.” He added, “Guthlac and Pega were very important figures in the early Christian history of England, so it is hugely exciting that we’ve been able to determine the chronology of what is clearly a historically significant site.”