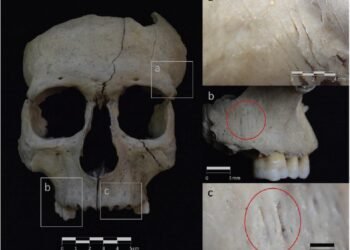

Archaeologists excavating the Church of St. Francis of Assisi in Krakow, Poland, have unearthed a 300-year-old medical prosthesis designed to assist a man with a cleft palate. This discovery marks the first of its kind not only in Poland but also in Europe.

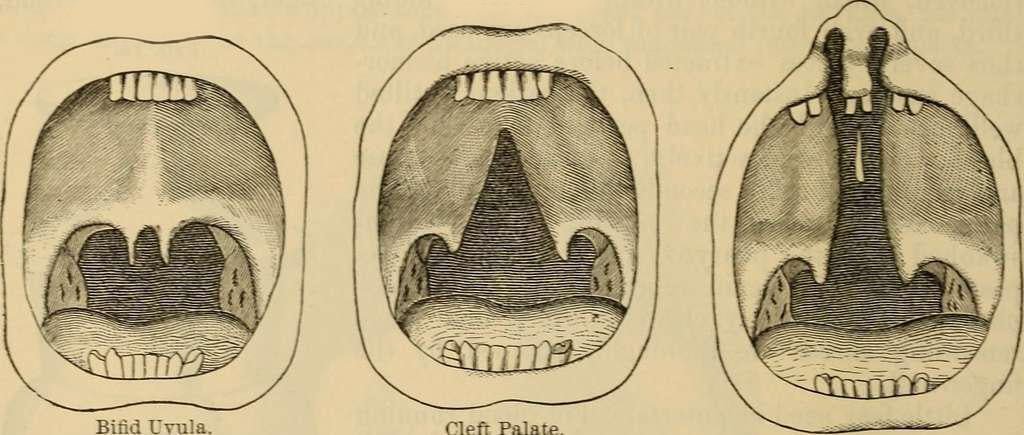

The individual, who lived around the 18th century and died at approximately 50 years old, had to cope with the effects of a cleft palate, a condition where the roof of the mouth, or hard palate, fails to fully close during fetal development. This results in a connection between the oral and nasal cavities, causing difficulties in breathing, speaking, and eating.

While today surgical interventions are available to correct such anomalies, the man from centuries ago resorted to a unique solution: a palatal obturator, an artificial device inserted into the mouth to replace the missing portion of the hard palate.

Described as “exceptional,” the prosthetic consists of a metal plate resembling the hard palate, attached to a wool pad for comfortable fitting into the mouth. This device, measuring 1.2 inches long and weighing about 0.2 ounces, aimed to restore the separation between the oral and nasal cavities, thereby enhancing the man’s quality of life.

Study first author Anna Spinek, an anthropologist at the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy in Poland, highlights the exceptional nature of this discovery, noting its scarcity in both institutional and private collections.

Analysis of the prosthetic’s composition revealed that the metal parts were primarily composed of copper, with notable traces of gold and silver. The wool pad, crucial for securing the device, contained silver iodide, likely added for its antimicrobial properties. The meticulous craftsmanship of the prosthesis indicates a level of sophistication in addressing medical challenges during that era.

While the exact functionality of the obturator remains uncertain, comparisons with similar devices from historical texts suggest its effectiveness in improving speech clarity and enhancing eating comfort.

The study was published in the April issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.