The Wisconsin Historical Society, in partnership with Native Nations in Wisconsin, has uncovered a cache of ancient dugout canoes in Lake Mendota near Madison.

This discovery, which began with the identification of two canoes in 2021 and 2022, has now expanded to at least ten, potentially eleven, canoes dating from various periods over the last 4,500 years.

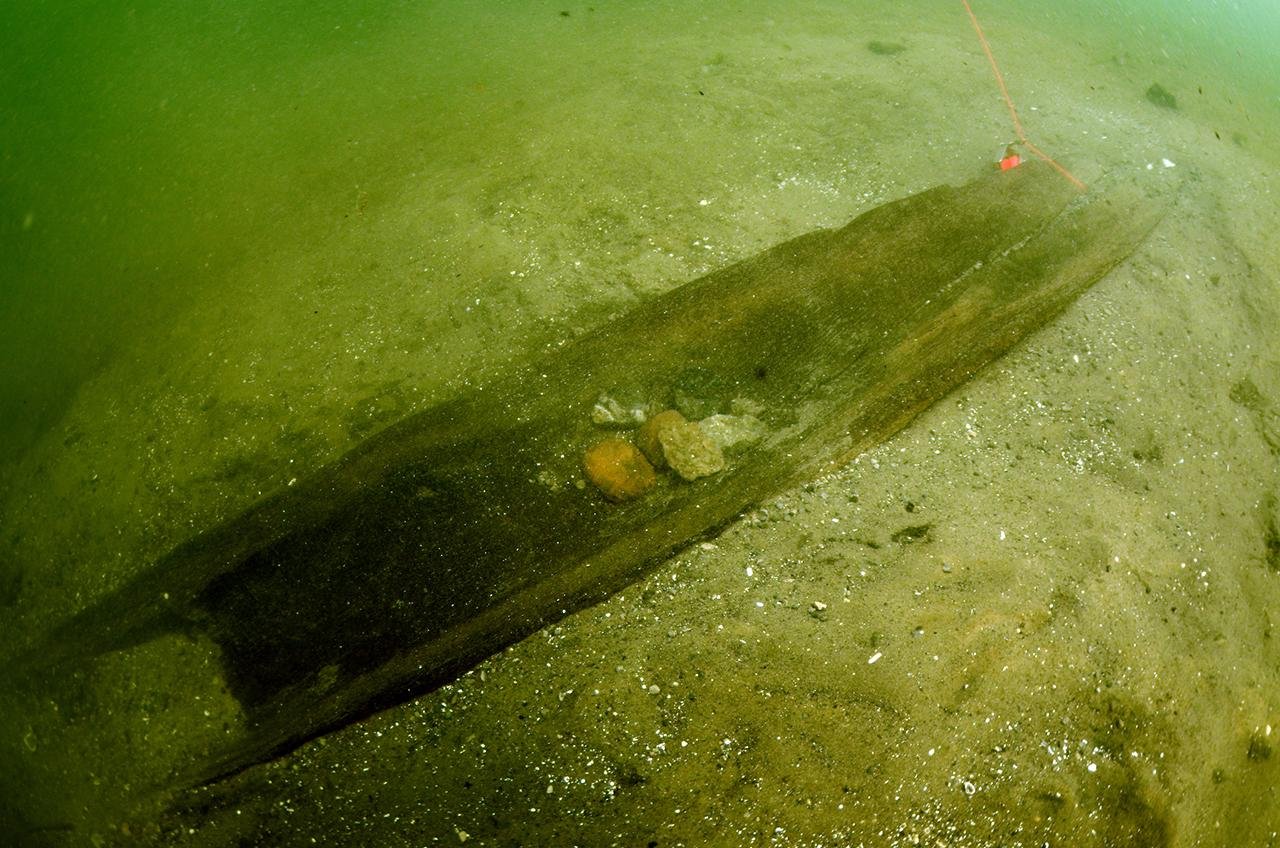

The initial discovery was made by Tamara Thomsen, a maritime archaeologist with the Wisconsin Historical Society, who found a partially obscured dugout canoe in June 2021. This canoe, carved from a single tree, was later dated to be approximately 1,200 years old. A subsequent discovery in 2022 of another canoe, estimated to be 3,000 years old, prompted further exploration of the lake bed.

Upon further investigation, archaeologists identified a grouping of at least ten unique canoes concentrated along what was likely an ancient shoreline. The oldest of these canoes dates back 4,500 years, making it the oldest known example in the Great Lakes region.

Dr. Amy Rosebrough, State Archaeologist for the Wisconsin Historical Society, remarked, “What we thought at first was an isolated discovery in Lake Mendota has evolved into a significant archaeological site with much to tell us about the people who lived and thrived in this area over thousands of years and also provides new evidence for major environmental shifts over time.”

The canoes were found at a depth of 30 feet, suggesting that they were once stored in shallow waters near the shore, which have since become submerged due to environmental changes. These ancient vessels, made from various types of wood including Elm, Ash, White Oak, Cottonwood, and Red Oak, indicate shifts in forest composition and climate over millennia.

Radiocarbon dating and wood type analysis, conducted by the USDA Forest Products Laboratory, revealed that the earliest canoe dates to around 2500 BCE. This period, known as the Late Archaic, showcases the advanced craftsmanship of early canoe makers who utilized the hard woods available to them despite their challenging nature for woodworking.

Archaeologists hypothesize that the canoes were intentionally submerged to prevent warping in freezing winter temperatures, a practice that likely continued over generations. This theory is supported by the consistent location of the canoes, suggesting a habitual storage area possibly near a living settlement.

Ground penetrating radar (GPR) surveys conducted by Bill Quackenbush, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation, and Larry Plucinski, Lake Superior Chippewa Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, have uncovered anomalies in the lakebed, hinting at a submerged ancient village. “We are excited to learn all we can from this site using the technology and tools available to us, and to continue to share the enduring stories and ingenuity of our ancestors,” said Quackenbush.

Due to their fragile state, the Wisconsin Historical Society has decided not to recover any more canoes from the site. The two previously recovered canoes are undergoing a preservation process at the State Archive Preservation Facility in Madison. This process, involving the use of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), is expected to stabilize the wood by 2026, after which the canoes will be freeze-dried at Texas A&M University to prepare them for public display.

The Wisconsin Historical Society plans to exhibit these canoes at the new Wisconsin History Center, set to open in 2027.