Archaeologists have unearthed a prehistoric campsite in South America where early hunter-gatherers butchered an extinct elephant relative more than 12,000 years ago.

The site, named Taguatagua 3, represents a temporary camp utilized by hunter-gatherers approximately 12,440-12,550 years ago. Among the remarkable discoveries at the site are the fossilized remains of a gomphothere, an extinct relative of modern elephants. These creatures, which roamed the Earth during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene epochs, were hunted and butchered by the inhabitants of the camp.

The site, named Taguatagua 3, represents a temporary camp utilized by hunter-gatherers approximately 12,440-12,550 years ago. Among the remarkable discoveries at the site are the fossilized remains of a gomphothere, an extinct relative of modern elephants. These creatures, which roamed the Earth during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene epochs, were hunted and butchered by the inhabitants of the camp.

The authors of the study, explain, “Taguatagua 3 helps us to understand better how the early humans adapted to fast-changing environments in central Chile during the late Pleistocene times.”

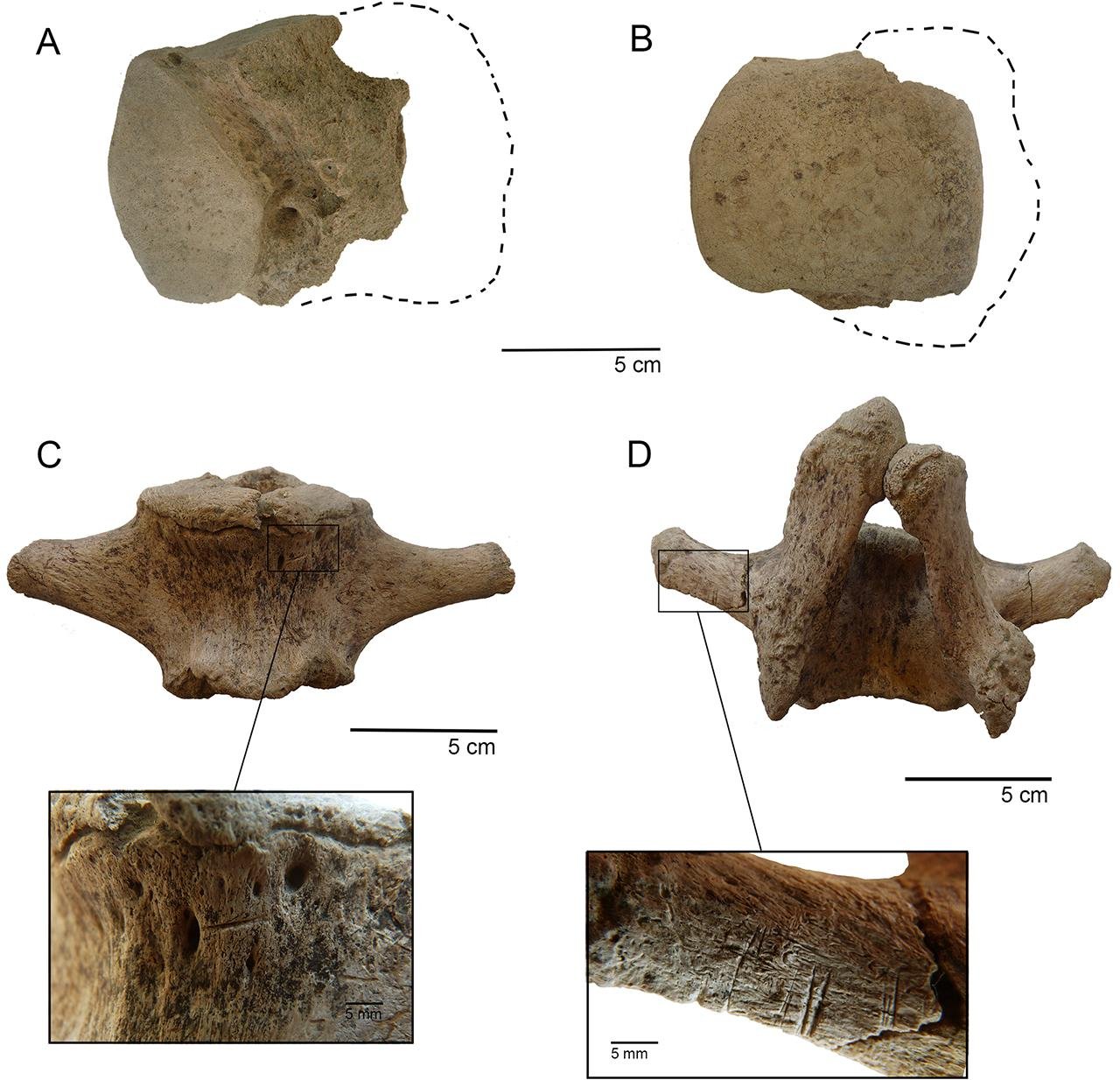

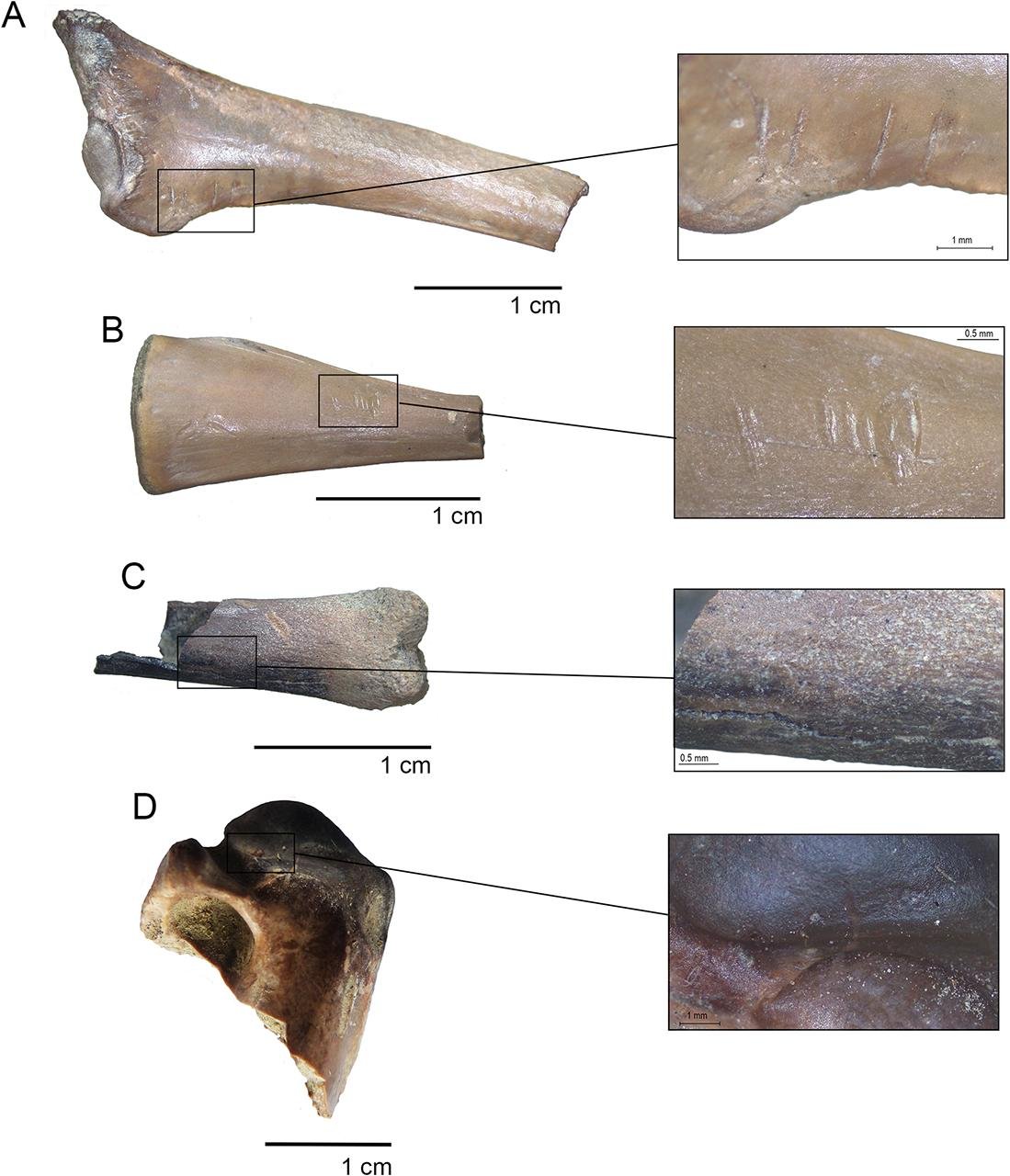

Evidence of butchery on the gomphothere bones, along with the presence of stone tools and other remains, indicates that the camp was primarily associated with the hunting and processing of these large mammals. However, the site also reveals evidence of diverse activities, suggesting a broader range of subsistence strategies.

Researchers found charred remains of plants and small animals like frogs and birds, indicating additional food processing activities at the site. Furthermore, the discovery of fossilized cactus seeds and bird eggshells suggests that the camp was specifically occupied during the dry season.

The findings imply that the Tagua Tagua Lake region served as a crucial hub for nomadic hunter-gatherer communities during the late Pleistocene, offering abundant, diverse, and predictable resources.

The study’s authors suggest that this area likely played a pivotal role in the mobility patterns of early humans in South America. The discovery adds to the ongoing debate surrounding the timing of human migration to the South American continent. While the exact timeline remains contentious among researchers, the findings from Taguatagua 3 contribute valuable information to the discussion.

The study’s detailed analysis of the archaeological assemblage, combined with ethnographic data and environmental context, offers a nuanced understanding of how early humans adapted to their surroundings.

The findings are detailed in a study published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.