A recent study, published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, has unveiled why Egypt’s iconic pyramids are concentrated along a narrow desert strip. Researchers from the University of North Carolina Wilmington have discovered an extinct branch of the Nile River, termed the Ahramat Branch, which played a crucial role in the transportation of materials for pyramid construction.

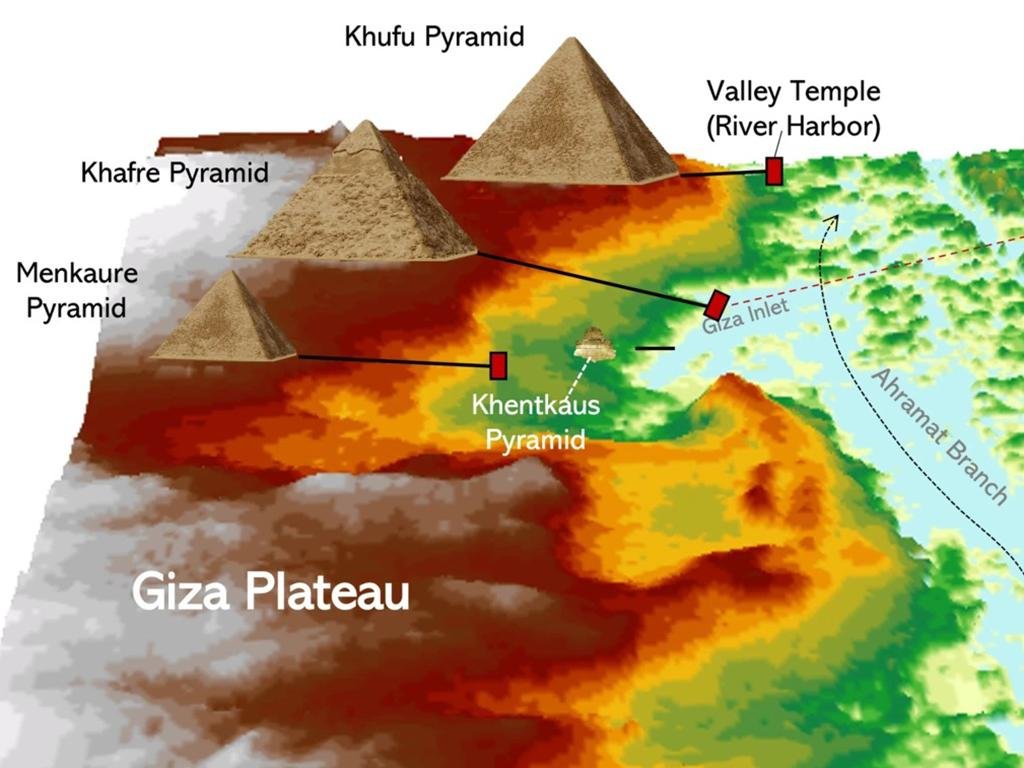

The study utilized advanced techniques, including radar satellite imagery, geophysical surveys, and deep soil coring, to investigate the subsurface structure and sedimentology in the Nile Valley adjacent to the pyramid clusters. This multifaceted approach revealed the existence of the Ahramat Branch, an ancient waterway that once ran near the Western Desert Plateau, home to most of the Egyptian pyramids. “The Ahramat Branch played a role in the monuments’ construction and was simultaneously active and used as a transportation waterway for workmen and building materials to the pyramids’ sites,” the study authors noted.

The Role of the Nile in Ancient Egypt

The Nile River has been fundamental to the growth and expansion of Egyptian civilization since the Pharaonic era. It provided essential resources, including sustenance and a primary mode of transportation for goods and building materials. Consequently, many of the major cities of the Egyptian civilization were established near the banks of the Nile and its branches. Over centuries, the primary channel of the Nile shifted, causing peripheral branches to silt up and cut off population centers from vital resources. This phenomenon is evident in the case of the pyramids along the Western Desert Plateau, where many pyramids are situated several kilometers from the current primary channel of the Nile.

Using radar satellite imagery, the researchers identified the Ahramat Branch’s remnants. This ancient branch connected the pyramids of the Old and Middle Kingdoms to the Nile through causeways and Valley Temples, which likely served as river harbors. The study suggests that the eastward migration and eventual abandonment of the Ahramat Branch resulted from a combination of tectonic activity, windblown sand incursion, and decreased river discharge due to drought and increased aridity.

Transporting Limestone Blocks and Construction Materials

The mystery of how ancient Egyptians moved limestone blocks, some weighing over a ton, has puzzled historians for centuries. The new study provides evidence that the Ahramat Branch facilitated the transportation of these massive stone blocks and other materials necessary for pyramid construction. Raised causeways connected the pyramids to river ports along the Nile’s bank, enabling efficient transport.

The researchers examined 31 pyramids located between Lisht, a village south of Cairo, and Giza, constructed over approximately 1,000 years beginning around 4,700 years ago. These pyramid complexes, built as tombs for Egyptian royals, often featured nearby tombs for high officials. Some of the granite blocks used in their construction were sourced from hundreds of miles away. The proximity of the Ahramat Branch to the pyramid sites suggests that it was “active and operational during the construction phase of these pyramids,” enabling the use of boats to transport workers and tools.

The study’s findings are bolstered by the use of historical maps from 1911, sediment cores, and radar satellite data, which allowed the researchers to trace the ancient waterway’s imprint. This comprehensive mapping provides a more complete picture of the ancient Egyptian landscape and supports the theory that the Nile’s ancient channel system was more complex and extensive than previously thought.

The research builds on previous studies, including one from 2022 that used evidence of ancient pollen grains to suggest that a waterway once cut through the present-day desert.

The discovery of the Ahramat Branch has significant implications for future research and conservation efforts. By mapping this hidden river system, researchers can better understand the environmental history of the Nile floodplain and prioritize locations for fieldwork investigation. The findings could also help locate the remains of settlements or undiscovered sites before they are lost to rapid urbanization.