Recent archaeological findings have uncovered the charred remains of an Iron Age settlement in the Pyrenees, believed to have been destroyed by Carthaginian forces led by General Hannibal during his legendary march on Rome over 2,200 years ago.

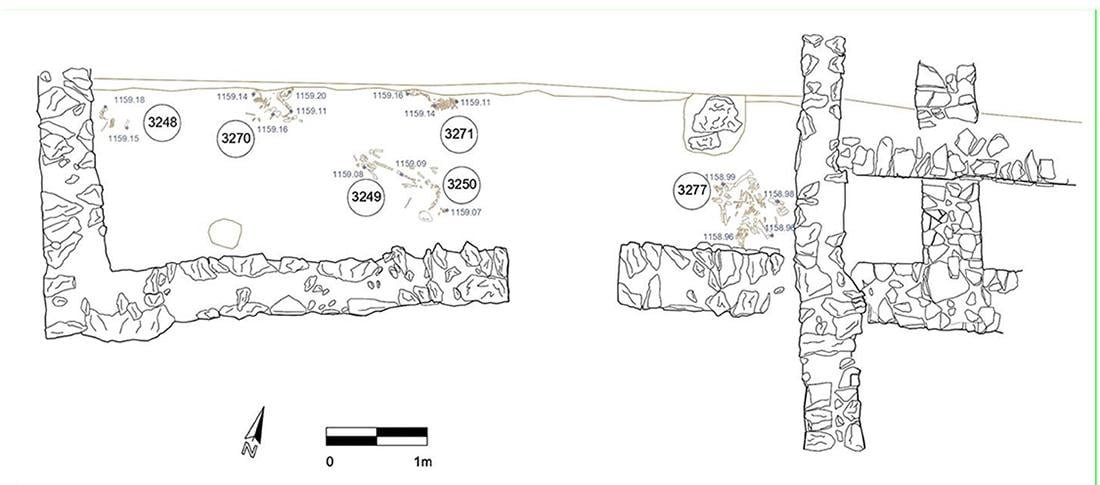

The settlement, known as Tossal de Baltarga, is located in the Eastern Pyrenees, roughly 70 miles north of Barcelona in Spain’s Catalonia region. Researchers, led by Oriol Olesti Vila, a professor of Antiquity and the Middle Ages at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, have published their findings in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology. The study details the destruction of a two-story farmhouse, known as Building G, which was completely incinerated, trapping livestock but leaving no human remains.

“This was a very large fire,” Olesti Vila told Live Science. “The roof and the ceiling were of wood, and two floors were separated by a wooden partition. … The whole building was destroyed.” The intense blaze that consumed Building G not only decimated the structure but also preserved a wealth of organic material, providing a snapshot of Iron Age life and its abrupt end due to a catastrophic event.

The devastation is linked to the late third century BCE, coinciding with Hannibal’s passage through the Pyrenees. Hannibal Barca, the Carthaginian general, famously marched his army, including war elephants, from Carthage in North Africa through Spain, southern France, and the Alps to invade Italy. His route brought him into conflict with local tribes, including the Cerretani, who inhabited Tossal de Baltarga.

Polybius, a Greek historian, recorded Hannibal’s skirmishes with tribes during his crossing of the Pyrenees, lending credence to the theory that the fire at Tossal de Baltarga was a result of these clashes. According to Olesti Vila, the settlement’s destruction was likely an act of deliberate arson by Hannibal’s troops, aimed at causing maximum damage.

The archaeological evidence supports this hypothesis. The remains of four sheep, a goat, and a horse were found in the lower floor of Building G, indicating that the animals were confined and unable to escape the fire. This confinement suggests that the inhabitants anticipated an attack, as it was unusual for livestock to be kept indoors. Additionally, the charred remains of a dog, likely tied up, were discovered in another building, further indicating the sudden and violent nature of the destruction.

Among the ruins, archaeologists found an iron pick and a gold earring hidden in a small pot on the second floor. The presence of these items, particularly the earring, suggests that the inhabitants had hidden valuable belongings in anticipation of trouble. “The single gold earring, too, seems to have been deliberately hidden inside a little pot on the second floor of the house, which could be further evidence that the householders suspected trouble,” said Olesti Vila.

The site of Tossal de Baltarga, home to the Cerretani, a pre-Roman people noted for cattle raising, was strategically located overlooking major trade routes and the river below. Despite the lack of defensive walls, its position provided a natural vantage point. The economic and strategic significance of these valleys made them a target during Hannibal’s campaign.

Building G’s upper floor was divided into areas for cooking and textile production, evidenced by spindles and loom weights, indicating that the household engaged in wool spinning and weaving. The discovery of grains such as oats and barley, along with cooking vessels containing residues of milk and pork stew, highlights the agricultural practices of the inhabitants. However, the absence of underground storage pits and grinding stones suggests that grain processing and storage might have been centralized at nearby sites, like El Castellot.

The settlement’s sudden destruction preserved a snapshot of the Iron Age economy and lifestyle. Tossal de Baltarga’s inhabitants participated in a complex network of trade and resource exploitation. Isotope analysis of the sheep remains revealed that some had grazed in lowland pastures, indicating exchange agreements with neighboring communities for resources such as salt and winter pastures. “These mountain communities were not isolated but connected with surrounding areas, exchanging goods and cultural practices,” Olesti Vila explained.

Following its destruction, Tossal de Baltarga was reoccupied and fortified by the Romans, who built substantial defenses, including an impressive watchtower. This reoccupation underscores the site’s continued strategic importance and the memory of its violent past.