A recent study proposes a revolutionary theory about the construction of Egypt’s Step Pyramid of Djoser, suggesting that ancient Egyptians may have used an advanced hydraulic lift system to raise the massive stone blocks. This new hypothesis challenges the long-standing belief that ramps and rollers were the primary methods used in building these monumental structures.

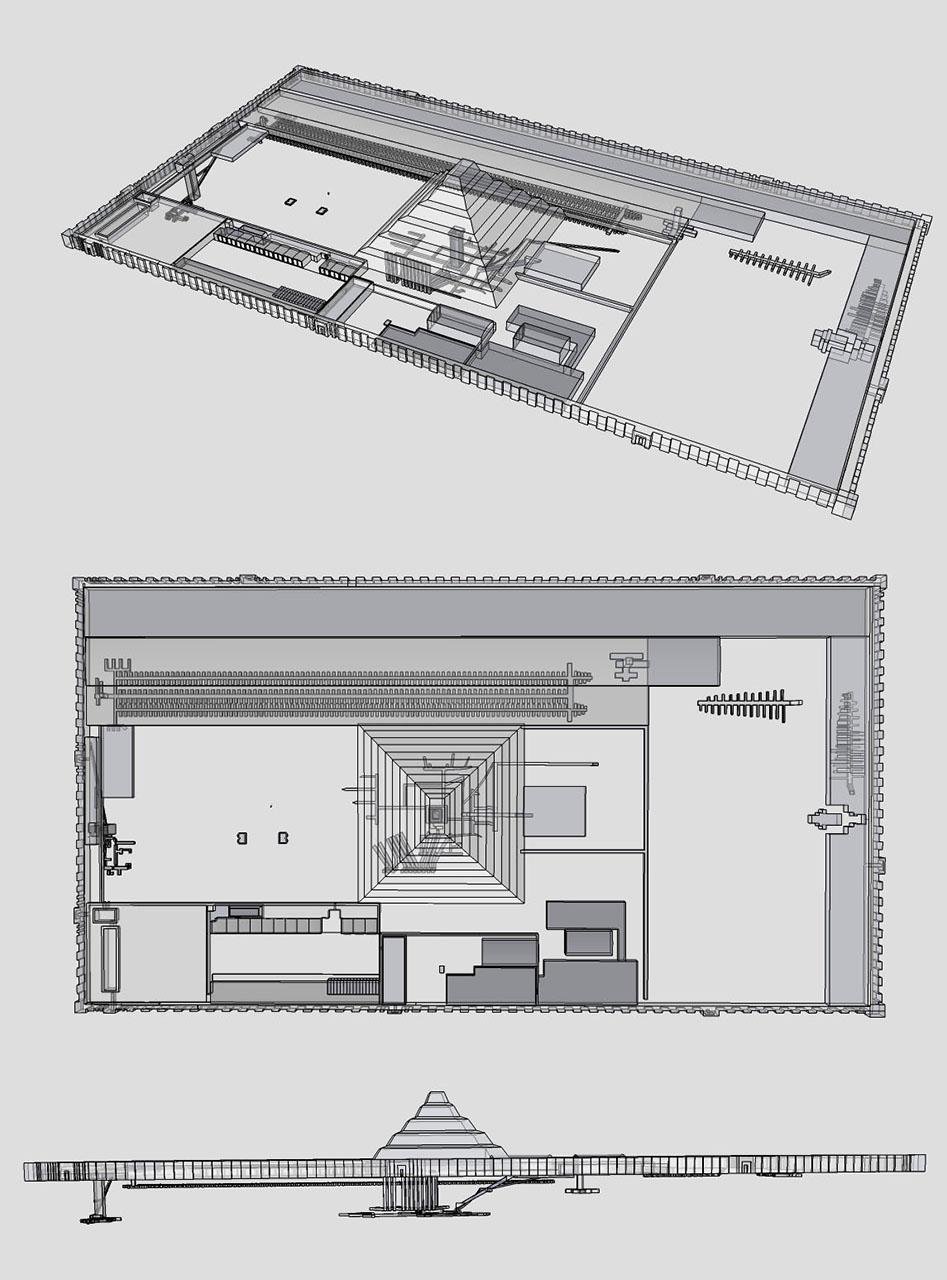

The Step Pyramid of Djoser, standing approximately 60 to 62 meters tall, is the earliest colossal stone building in Egypt, constructed during the Third Dynasty under the reign of Pharaoh Djoser (circa 2670–2650 BCE). Located on the Saqqara Plateau, south of Giza, it forms the centerpiece of a vast mortuary complex. Despite extensive studies over the years, the precise methods employed in its construction have remained elusive.

The study, led by Dr. Xavier Landreau from the CEA Paleotechnic Institute and his team of French engineers, hydrologists, and material scientists, utilized satellite radar imagery and historical archaeological reports to uncover new insights into the pyramid’s construction. Their research points to a sophisticated water management system that may have facilitated the construction process.

Dr. Landreau explained in an interview with Haaretz, “Satellite imagery clearly shows that a rectangular stone enclosure known as Gisr el-Mudir, located west of the Saqqara necropolis, has all the technical characteristics of a check dam. This feature would have been used to control the flow of flash floods and capture heavy objects coming from upriver.”

The researchers propose that the Pyramid of Djoser was built using a hydraulic lift mechanism that raised stone blocks through the center of the structure. This method, described as “volcano fashion,” would involve floating limestone blocks upward using water pressure and then placing them in their respective positions.

The key to this hydraulic system lies in the complex water management infrastructure surrounding the pyramid. The Gisr el-Mudir, a massive stone enclosure, and a dry moat with successive, deep compartments near the pyramid’s southern section, likely played crucial roles. The study suggests that these structures formed part of an integrated system for regulating water flow and improving water quality.

In their paper, the authors explain: “The monumental linear rock-cut structure in the southern section of the moat combines the technical requirements of a water treatment facility: a settling basin, a retention basin, and a purification system. This setup likely directed sediment-free water to feed the hydraulic lift system within the pyramid.”

The researchers highlight that the Third Dynasty period coincided with the latter part of the Green Sahara period when northern Africa experienced more rainfall and lush vegetation. The Abusir Wadi, an ancient stream flowing from the mountains west of the Saqqara Plateau, would have provided ample water to support such a hydraulic system.

“Before the Fourth Dynasty, there were more problems with floods than with a lack of water,” Dr. Landreau noted, emphasizing the need for effective water management systems at the time.

This new hypothesis not only offers a plausible explanation for the construction of the Pyramid of Djoser but also underscores the advanced understanding of hydraulic engineering possessed by the ancient Egyptians. If proven correct, it would revolutionize our understanding of ancient Egyptian engineering and architectural techniques.

The study’s authors acknowledge that further onsite research is necessary to validate their theory. This includes reconstructing the water flow within the pyramid shafts and investigating the historical water levels of the Abusir Wadi to confirm its viability as a water source.