Recent archaeological excavations in central Norway have uncovered three Iron and Viking Age mortuary houses.

These discoveries were made in the village of Vinjeøra, in an area known as Skeiet, and have been detailed in a study published in the journal Medieval Archaeology by Dr. Raymond Sauvage and Dr. Richard Macphail. The findings challenge previous assumptions about the use of mortuary houses in pre-Christian Scandinavia and suggest a complex set of rituals involving the living and the dead.

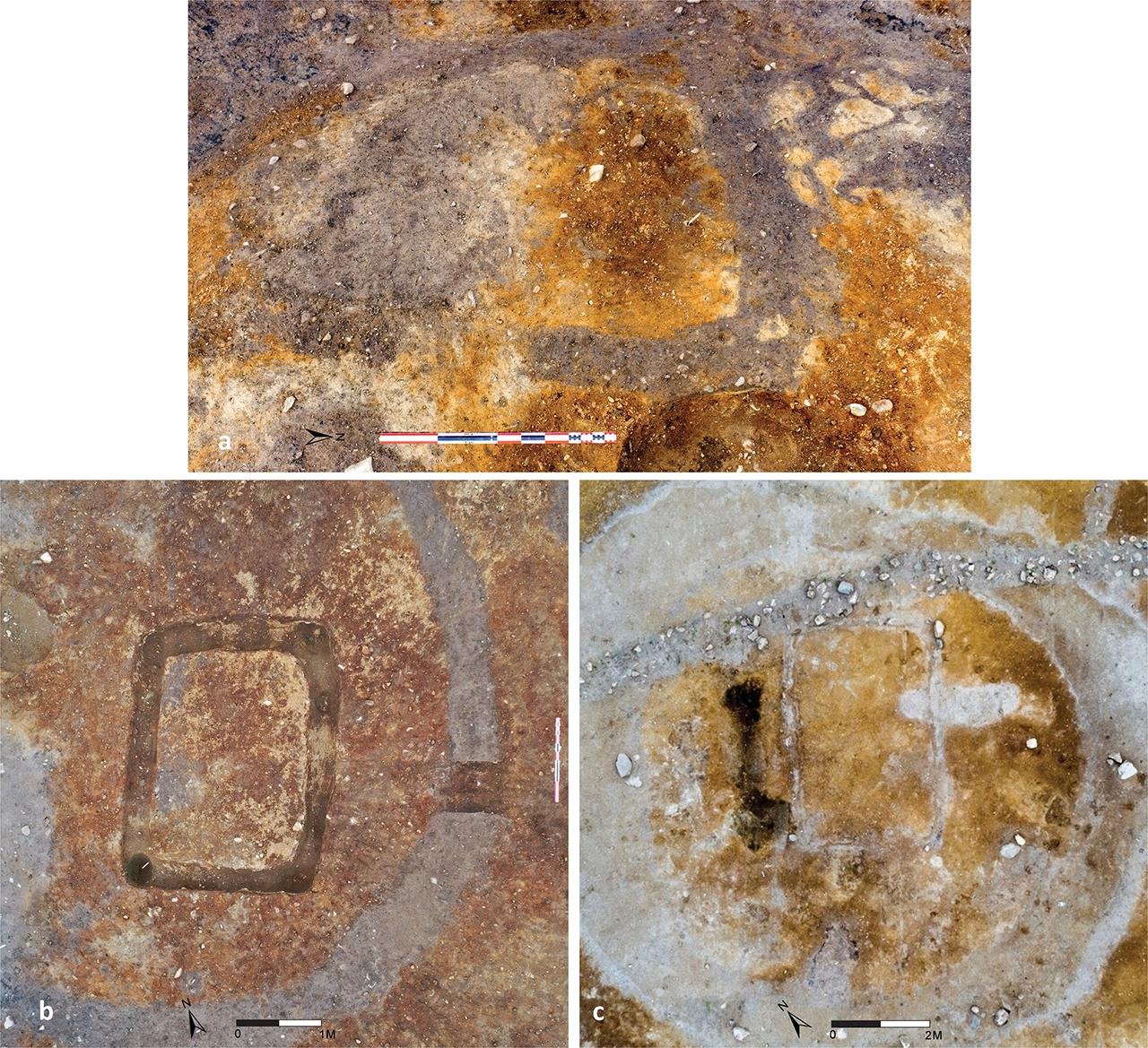

The excavation of these mortuary houses was triggered by planned road construction between 2019 and 2020. The area had been partially investigated in 1996, revealing a pre-Christian cemetery. However, it wasn’t until the more recent excavations that the true extent of the site was understood. Alongside flattened burial mounds, archaeologists discovered three mortuary houses, dating from CE 500 to CE 950. These structures are unique among the mortuary houses found elsewhere in Scandinavia, including 12 others in Norway and one in Sweden, due to the absence of human remains.

Mortuary houses, commonly found in ancient cemeteries, serve various functions, including housing graves or storing cremated remains. They could also be places where the living would leave offerings or perform rituals to honor the deceased. However, the mortuary houses in Vinjeøra differ significantly. As Dr. Sauvage, an archaeologist from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, noted, “We did not find any evidence of a permanent tomb or a buried person inside the houses.” Instead, these structures appeared to be designed for repeated visits by the living.

The presence of doors and entrances, an unusual feature for such structures, supports this interpretation. These entrances were low, requiring visitors to crouch, which may have been a deliberate design to create an intimate, reverent atmosphere. “Based on the relationship between the size of the mound and the plan of the house, we must assume that one would have to crouch,” Dr. Sauvage explained. “The room inside must have been quite small and dark, while the door must have let in some light that illuminated parts of the interior.”

The mortuary houses at Vinjeøra appear to reflect evolving burial practices over several centuries. The first structure, built between CE 450 and 600, corresponds to a period when cremation was the predominant burial method. A second structure, dating from CE 600 to 800, aligns with a shift towards more frequent inhumations, or burials of bodies. The third house, erected between CE 800 and the late 900s, came after inhumation had completely replaced cremation. Despite these changes in burial customs, the mortuary houses themselves remained an important part of funerary rituals for nearly 200 years.

Dr. Sauvage suggests that these houses may have served as sites for private, family-centered rituals. “The mortuary houses show a more stable continuity in use, probably related to the families’ own tradition of venerating their deceased and ancestors,” he said. This continuity contrasts with the more public and evolving burial practices observed elsewhere, which may have been influenced by external factors such as travel, contact with other cultures, and changing societal values.

Although no human remains were found inside the mortuary houses, other artifacts such as fragments of bone, arrowheads, and nails were discovered, which provide clues about their use. The remains of a horse, along with other animal bones showing signs of burning, suggest that sacrificial rituals, possibly akin to the Norse blót, were performed. These rituals might have included the preparation and sharing of meals as part of funerary rites, reflecting a belief in ongoing interaction between the living and the dead.

The construction of the mortuary houses, resembling contemporary dwellings, could also indicate that the deceased were considered to continue “living” in their burial mounds. However, since no actual burials were found within these houses, another possibility is that they functioned as temporary resting places for the dead while their bodies were prepared for more permanent interment. This practice is reminiscent of the burial rituals described by the 10th-century traveler Ibn Fadlan, who observed a Norse funeral where the body was stored in a wooden chamber for several days.

Despite the progress made in understanding these mortuary houses, many questions remain unanswered. Dr. Sauvage emphasized the need for further research: “Future studies should focus more on the interior to get better data about their use. Our evidence was fragmented, and there are several unanswered questions such as how the interior looked, whether there was a designated space to lay out the body, and how the entrances looked.”