A team of archaeologists has uncovered the remains of an ancient farming society in Morocco, dating back over 5,000 years. The site, known as Oued Beht, is the oldest agricultural complex found in Africa outside the Nile Valley, dating to between 3400 and 2900 BCE. This groundbreaking discovery significantly alters the understanding of North African prehistory and highlights the region’s critical role in the development of Mediterranean societies during the Neolithic period.

The discovery was reported in the journal Antiquity and led by an international team including Professor Cyprian Broodbank from the University of Cambridge, Professor Youssef Bokbot from Morocco’s National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage (INSAP), and Professor Giulio Lucarini from Italy’s National Research Council. Oued Beht is located in the Maghreb, a region that has long been recognized as a crossroads of Mediterranean and African cultures, but its role during the Neolithic period had remained largely unexplored.

For decades, archaeologists believed that the Maghreb, located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert, was primarily inhabited by nomadic pastoralists during this time. However, the discovery of Oued Beht changes this narrative, demonstrating that a highly developed farming society thrived in the region. Broodbank said, “For over thirty years I have been convinced that Mediterranean archaeology has been missing something fundamental in later prehistoric North Africa. Now, at last, we know that was right.”

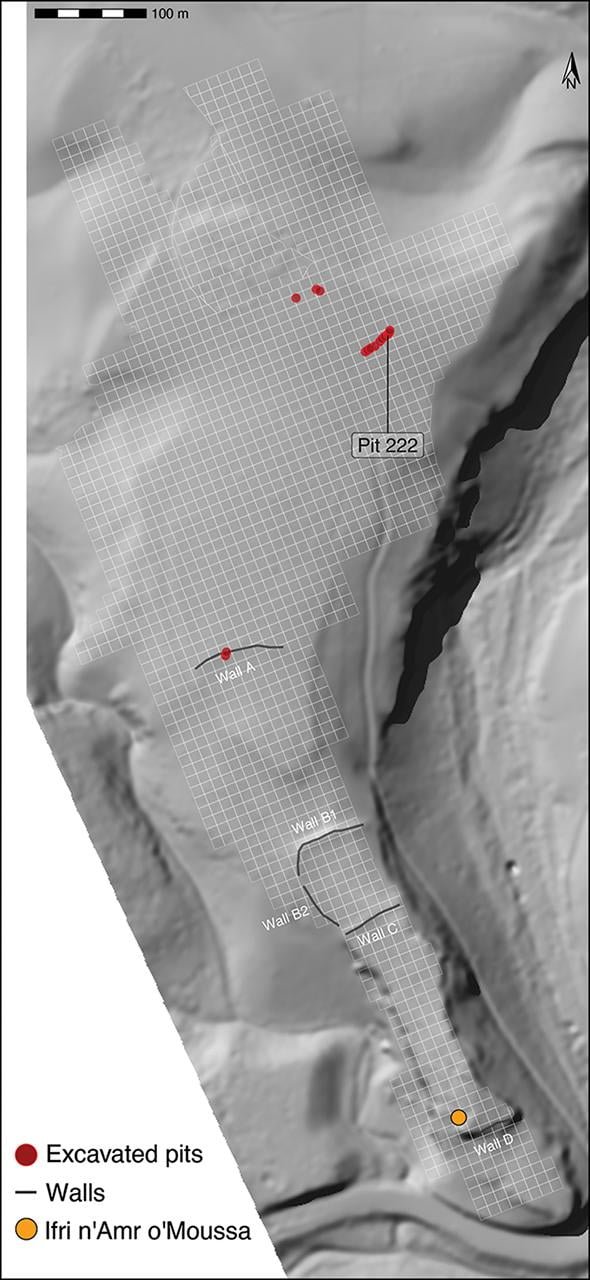

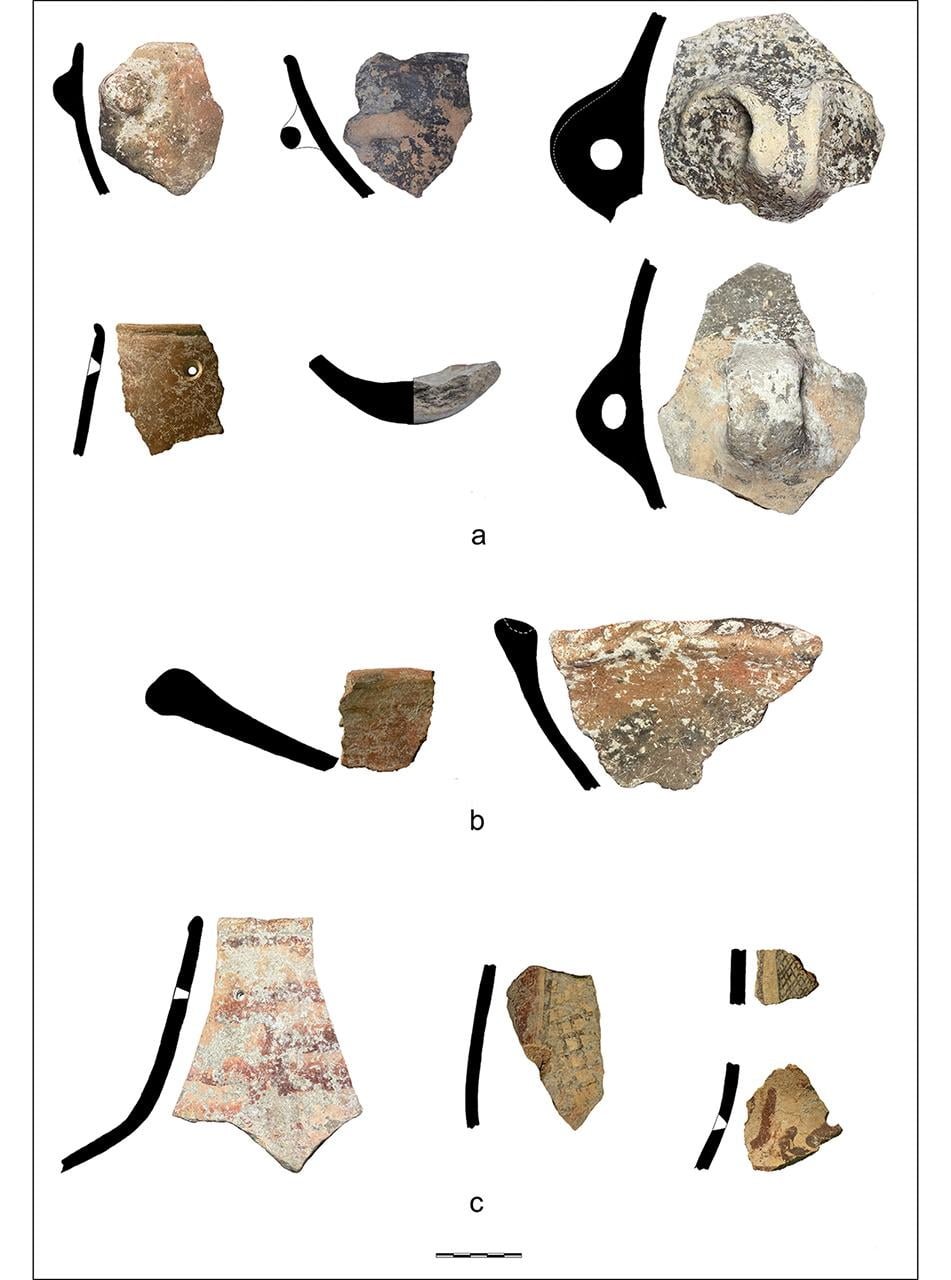

Excavations at the site have uncovered an abundance of artifacts, including domesticated plant and animal remains, pottery, and stone tools. These findings suggest that the society at Oued Beht was highly organized and engaged in large-scale farming. Evidence indicates that they cultivated crops like barley, wheat, peas, olives, and pistachios, and raised livestock such as sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle. The site also revealed extensive storage pits, which point to advanced agricultural practices and the ability to store surplus food.

The scale of the settlement is impressive, with the archaeological team comparing it to Early Bronze Age Troy in size. Thousands of stone tools, such as axes, along with elaborately decorated pottery, were found, indicating a thriving community of hundreds of people. According to Lucarini, “The sheer quantity of pottery shards and polished stone tools found at the site is unprecedented.”

One of the most exciting aspects of the discovery is its broader implications for understanding early Mediterranean and African connections. Archaeological evidence from the Iberian Peninsula, such as ivory and ostrich eggshells, had long suggested cultural links between North Africa and Europe during this period, but the exact nature of these connections remained unclear. The discovery of similar storage pits in both Morocco and Iberia points to significant trade and interaction across the Strait of Gibraltar. This suggests that the Maghreb was not an isolated region but a critical hub in the wider Mediterranean world.

Rather than being a marginal area dominated by nomadic herders, it was home to a complex, settled agricultural society that contributed to the broader development of Mediterranean civilization. As the study authors wrote, “It is crucial to consider Oued Beht within a wider co-evolving and connective framework embracing peoples on both sides of the Mediterranean-Atlantic gateway during the later fourth and third millennia BCE.”

The researchers argue that the absence of previous findings in the region was not due to a lack of prehistoric activity but rather to the relative lack of investigation. The Oued Beht site provides compelling evidence that North Africa played a far more central role in early Mediterranean history than previously thought.