A remarkable 2,800-year-old burial mound unearthed in southern Siberia is shedding new light on the origins of the Scythians, a nomadic people known for their horse-riding culture and elaborate funerary practices.

Discovered in the Tuva region, the burial site contains the remains of an elite individual buried with 18 sacrificed horses and at least one human, possibly a woman, who may have been sacrificed as part of the burial ritual. Researchers believe this discovery to be one of the earliest known examples of Scythian-like burial customs.

The burial mound, or kurgan, is located in an area known as the “Siberian Valley of the Kings,” a valley filled with thousands of similar mounds. Through radiocarbon dating, archaeologists determined that the site dates back to the late ninth century BCE, at the transition between the Bronze and Iron Ages. The site provides some of the earliest evidence of Scythian burial practices, which would later be seen in Scythian burials across the Eurasian steppes.

According to Gino Caspari, an archaeologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland and the study’s lead researcher, “Unearthing some of the earliest evidence of a unique cultural phenomenon is a privilege and a childhood dream come true.” Caspari and his team published their findings in the journal Antiquity.

The Scythians, a nomadic people who thrived between 900 and 200 BCE., were known for their exceptional horsemanship, artistry, and warrior skills. They played a significant role in the ancient world, interacting with—and often being feared by—cultures such as the Greeks, Assyrians, and Persians.

The Scythians left no written records of their own. However, fragments of their speech, known from inscriptions and words quoted by ancient authors, along with an analysis of their names, suggest that the language was Indo-European, specifically belonging to the Iranic branch of the Indo-Iranic language family.

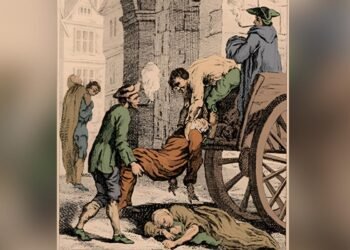

Much of what we know about them comes from external sources, such as the Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote about their elaborate sacrificial burial rituals in the fifth century BCE. Herodotus described how the Scythians honored their deceased elite with lavish ceremonies, often sacrificing humans and horses. According to his accounts, the horses would be gutted, stuffed, and arranged alongside the sacrificed humans to appear as though they were riding around the burial mound. The discovery of the burial mound in Tuva, with its sacrificed horses and human remains, aligns closely with these descriptions, suggesting that the Scythians’ funerary practices may have deeper roots in the cultures of southern Siberia.

The artifacts found at the site, including horse-riding gear and items decorated with animals, also draw strong parallels to the later Scythian culture. Many of the horse skeletons still had brass bits lodged between their teeth, and the burial mound contained Scythian-like objects, indicating that this culture’s unique practices may have begun earlier and further east than previously thought. Caspari suggests that the funerary traditions seen in southern Siberia may have influenced later Scythian practices in areas such as Ukraine and southwest Russia.

Interestingly, the findings also point to connections between the early Scythian culture and the horse cultures of Mongolia. Researchers have noted similarities between the burial mound in Tuva and Late Bronze Age graves found in Mongolia.

Dr. Caspari and his team believe that these funerary practices may have played a crucial role in the broader cultural and political transformations that swept across Eurasia during this period. “Our findings highlight the importance of Inner Asia in the development of transcontinental cultural connections,” Caspari said, adding that the discovery “suggests that these funerary practices played a role in the emergence of later pastoralist empires.”