Recent research into 4,500-year-old pottery from the ancient Syrian town of Tel Hama has uncovered remarkable evidence of child labor in the Early Bronze Age. Led by Dr. Akiva Sanders from Tel Aviv University, in collaboration with researchers from the National Museum in Copenhagen, the study analyzed 450 pottery vessels made during the peak of the Ebla Kingdom, one of the most significant early city-states of the Levant. The research, published in the journal Childhood in the Past, reveals that approximately two-thirds of these vessels were crafted by children as young as seven.

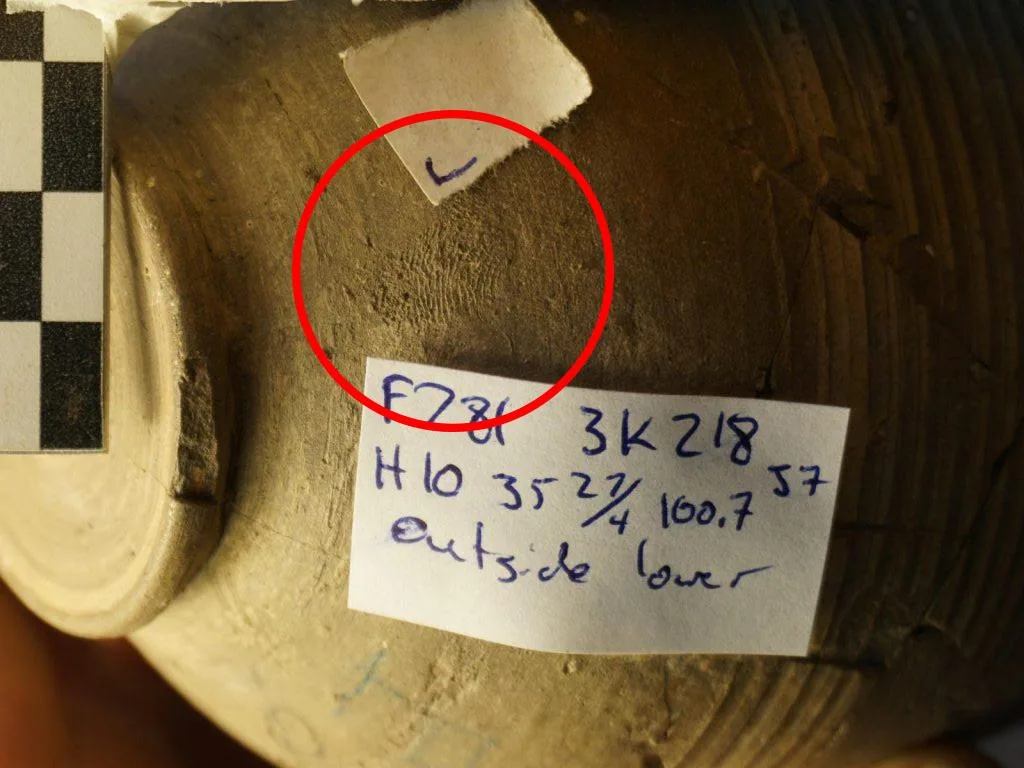

Fingerprint analysis on the pottery offered a key insight into the role children played in the industrial production of pottery in Tel Hama, which was located on the southern edge of the Ebla Kingdom. Fingerprints, which remain unchanged throughout a person’s life, allowed the researchers to estimate the age and sex of the potters based on palm size and the density of the fingerprint ridges. Their findings showed that the majority of these vessels, primarily everyday items such as cups, were made by children, while older men were responsible for the remaining third.

Dr. Sanders explained, “At its peak, roughly from 2400 to 2000 BCE, the cities associated with the Kingdom of Ebla began to rely on child labor for the production of ceramics. The children, starting at age seven, were trained to create cups as uniformly as possible, which were used both in everyday life and at royal banquets. The demand for these cups was high, especially during the alcohol-fueled feasts held at these banquets, where cups were frequently broken and needed to be quickly replaced.”

This use of child labor in the pottery industry mirrored trends seen in later periods, such as the Industrial Revolution in Europe and America, where children were similarly taught repetitive, precise movements to standardize production. The analysis showed that the production of pottery was highly gender-balanced, with boys and girls equally involved in the work, particularly during the kingdom’s peak.

However, the study also reveals a more personal and creative side of childhood in this ancient society. Beyond their assigned tasks, children created small figurines and miniature vessels—creations that appeared to be entirely independent of adult involvement. “These children taught each other to make tiny figurines and vessels, likely as an outlet for their creativity and imagination,” said Dr. Sanders. “It seems that, despite the pressures of their labor, these young potters found ways to express themselves artistically.”

The pottery from Tel Hama, excavated in the 1930s and stored in Denmark’s National Museum since then, provided a wealth of information not only about the technical skills of these young potters but also about the broader social dynamics of the time. As cities like those in the Ebla Kingdom began to grow and urbanize, there was an increasing centralization of production, with pottery workshops reflecting this shift.

In Tel Hama, older children, typically around the ages of 12 and 13, initially dominated the ceramic industry. However, as demand for more uniform pottery grew, particularly for royal banquets, the kingdom began to train younger children to meet the increased need for cups. This reliance on child labor, while common in many ancient and more recent societies, complicates our understanding of childhood in the past.