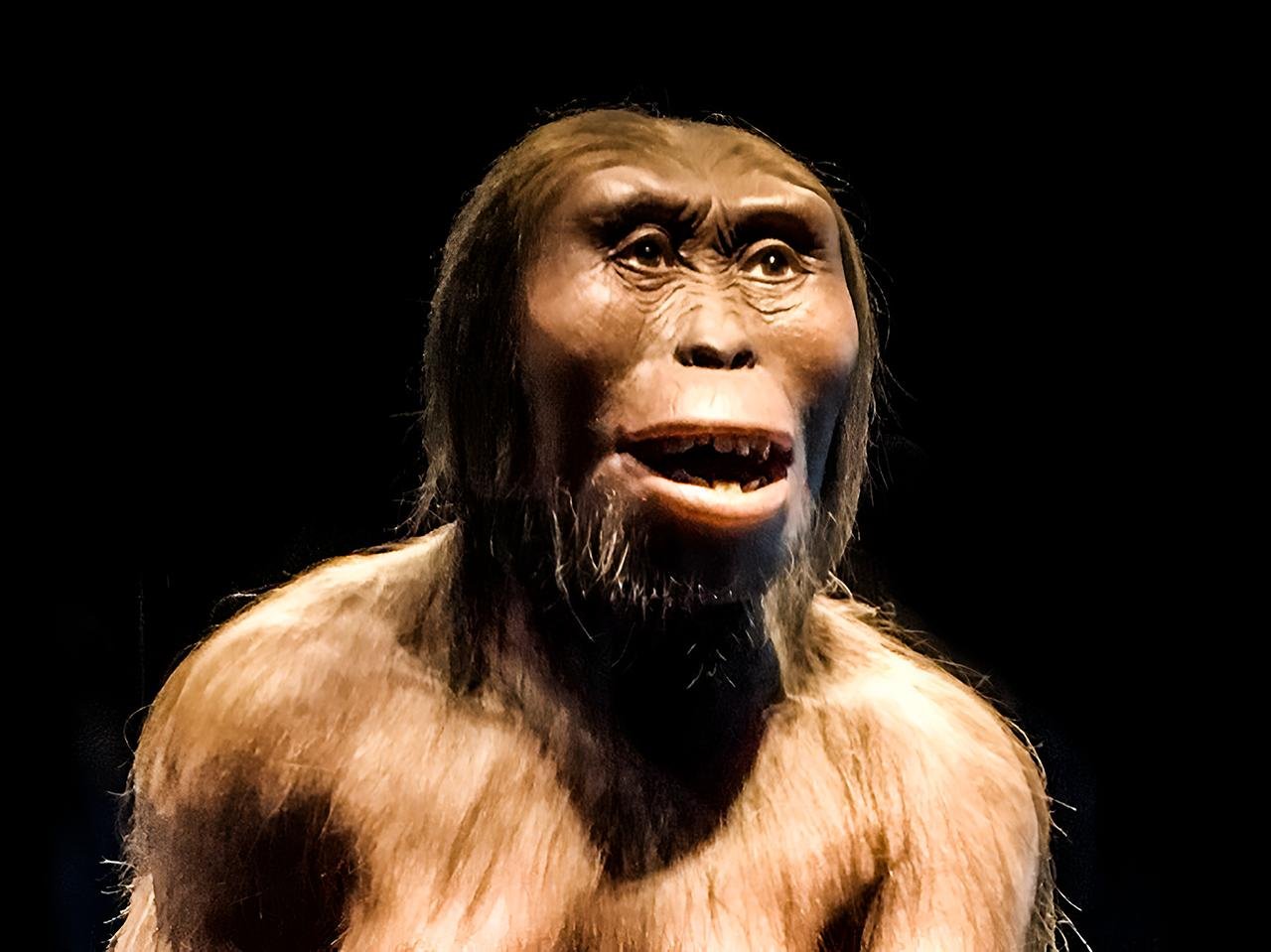

A recent study has challenged previous assumptions about early human tool use by examining the hand structure of ancient hominins, specifically the Australopithecus genus.

This analysis, conducted by researchers from Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen and published in the Journal of Human Evolution, focuses on muscle attachment sites in the hands of three Australopithecus species: A. afarensis, A. africanus, and A. sediba. The findings reveal that these species may have been capable of complex manual tasks previously thought unique to the Homo genus.

Traditionally, researchers assumed that the hands of Australopithecus species were not dexterous enough for tool-making, which was believed to have emerged with later hominins like Homo habilis. However, a detailed examination of the hand muscles, tendons, and bone attachment sites suggests that some Australopithecus species may have developed early tool-manipulation capabilities over three million years ago, well before the emergence of Homo. The lead researcher, Jana Kunze, explained, “This unique functionality provided early hominins with the dexterity needed to manipulate objects — including tools — effectively, paving the way for both technological and cultural progress.”

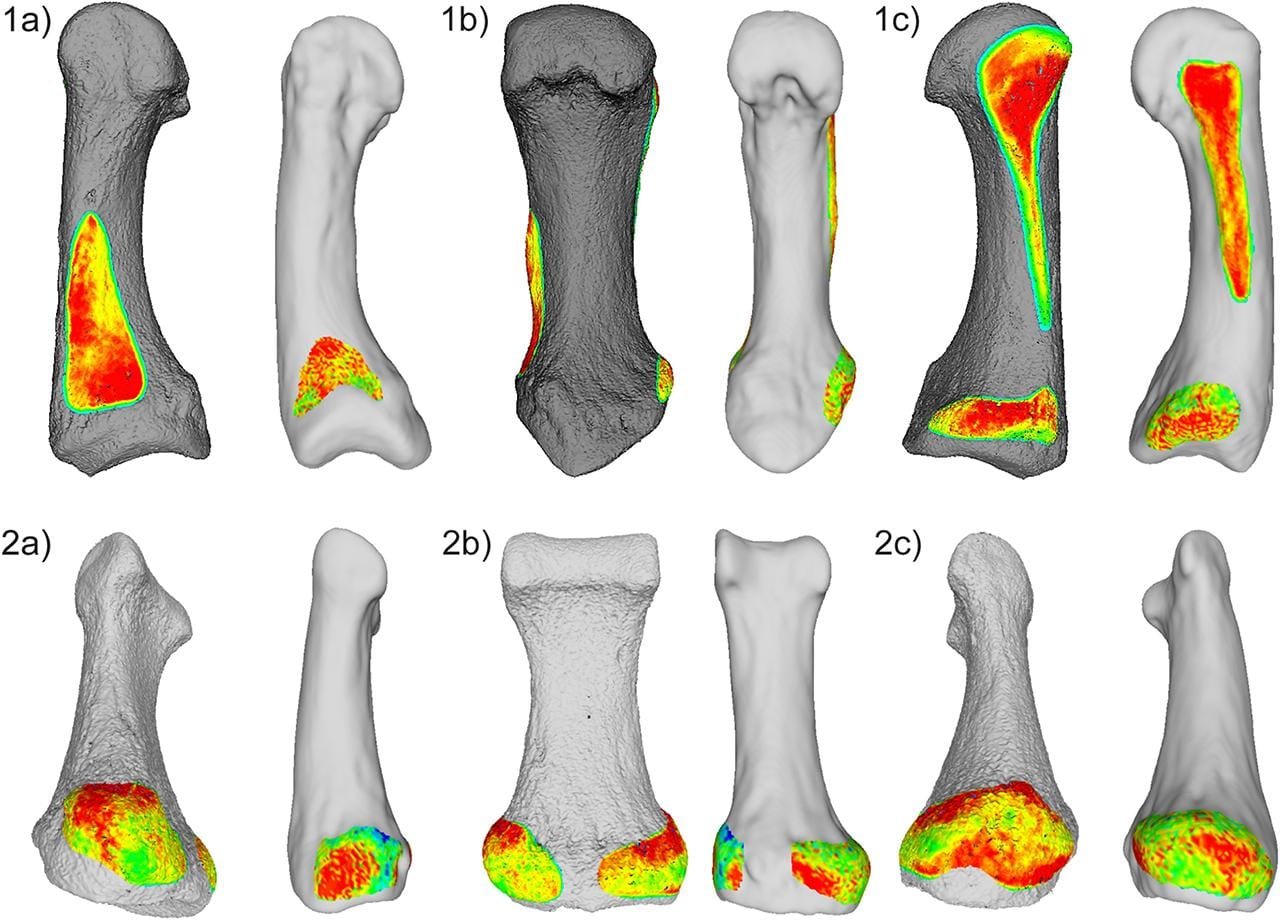

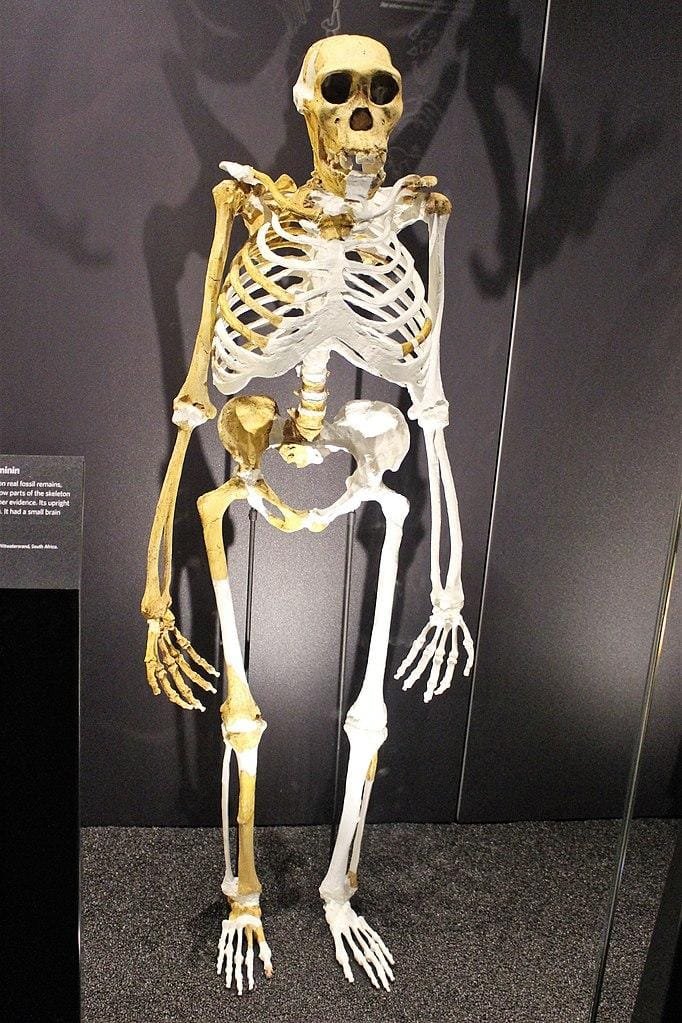

The study used 3D models to reconstruct the biomechanics of hand bones and analyzed entheses (muscle attachment sites) to understand how these hands were used. These adaptations in A. afarensis (famous for the “Lucy” specimen), A. africanus, and A. sediba indicate varying levels of humanlike and apelike hand traits, suggesting that each species likely engaged in different kinds of manual behaviors, potentially including tool use.

Australopithecus sediba, which lived approximately 2 million years ago, had the most humanlike hand anatomy, featuring a strong pinky muscle that suggests a capacity for precision gripping similar to later human species. This may have enabled A. sediba to engage in tasks requiring power grasping and intricate manipulation. “The co-evolution of the thumb and pinky were decisive for hominin biocultural evolution,” Kunze remarked, adding that this anatomical foundation set the stage for advanced dexterity in Homo species. In contrast, the older A. afarensis, which lived around 3 million years ago, displayed a blend of traits that allowed both climbing and rudimentary manual manipulation, suggesting that these early hominins may have used their hands for both locomotion and simple tool tasks.

The discovery of 3.3-million-year-old stone tools at the Lomekwi site in Kenya in 2015 sparked speculation that A. afarensis might have been capable of tool use. The new study adds weight to this hypothesis, with study co-author Fotios Alexandros Karakostis commenting “While we can’t definitively say that these early humans crafted stone tools, our findings demonstrate that their hands were frequently used in ways that closely align with the actions necessary for human tool manipulation.” Though there is no direct evidence linking A. afarensis to the Lomekwi tools, the structural adaptations in its hand anatomy imply some capacity for grasping and handling objects.

Overall, this study suggests that Australopithecus species were capable of humanlike manipulation patterns, hinting that the development of tool use and its cultural significance began earlier than once thought. This discovery reframes our understanding of early hominin behavior.

Comments 0