A recent study published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences examines the Late Bronze Age swords of the Balearic Islands in Spain, which date back to between 1000 and 800 BCE. These remarkable artifacts reveal the region’s dynamic engagement with the interconnected Mediterranean world, showcasing a fusion of local traditions and foreign innovations. The study, led by Laura Perelló Mateo of the University of the Balearic Islands, employed advanced analytical techniques to examine these swords’ manufacturing, material composition, and cultural significance.

Between 1400 and 1300 BCE, the Balearic Islands experienced a significant increase in mobility and cultural exchange, mirroring broader trends across the Western Mediterranean. This period of heightened connectivity brought new materials, technologies, and ideas to the islands. For example, the total weight of metal artifacts in Mallorca, Ibiza, and Formentera rose dramatically from 2.15 kg in the Early Bronze Age to 53 kg in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, reflecting an influx of copper and tin.

This exchange gave rise to novel objects like chest plates, belts, and mirrors, which had no precedent in the local archaeological record. Swords, in particular, stand out as symbols of cultural and technological hybridization. While they drew inspiration from continental Europe, their design and function evolved uniquely in the Balearic context.

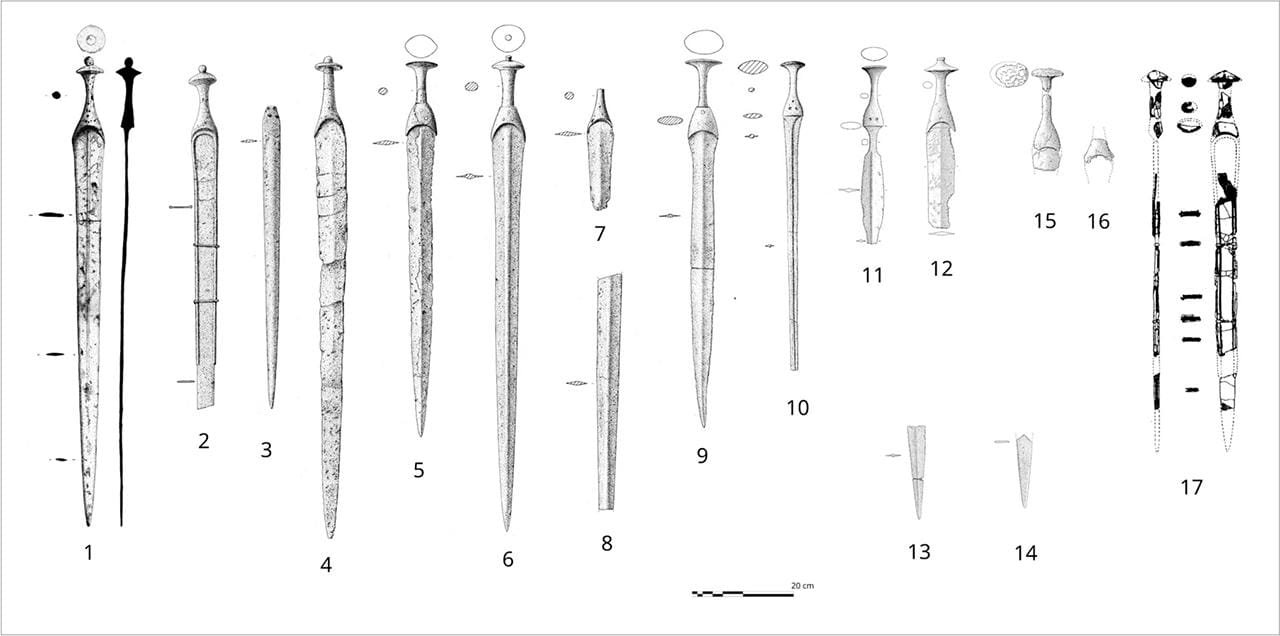

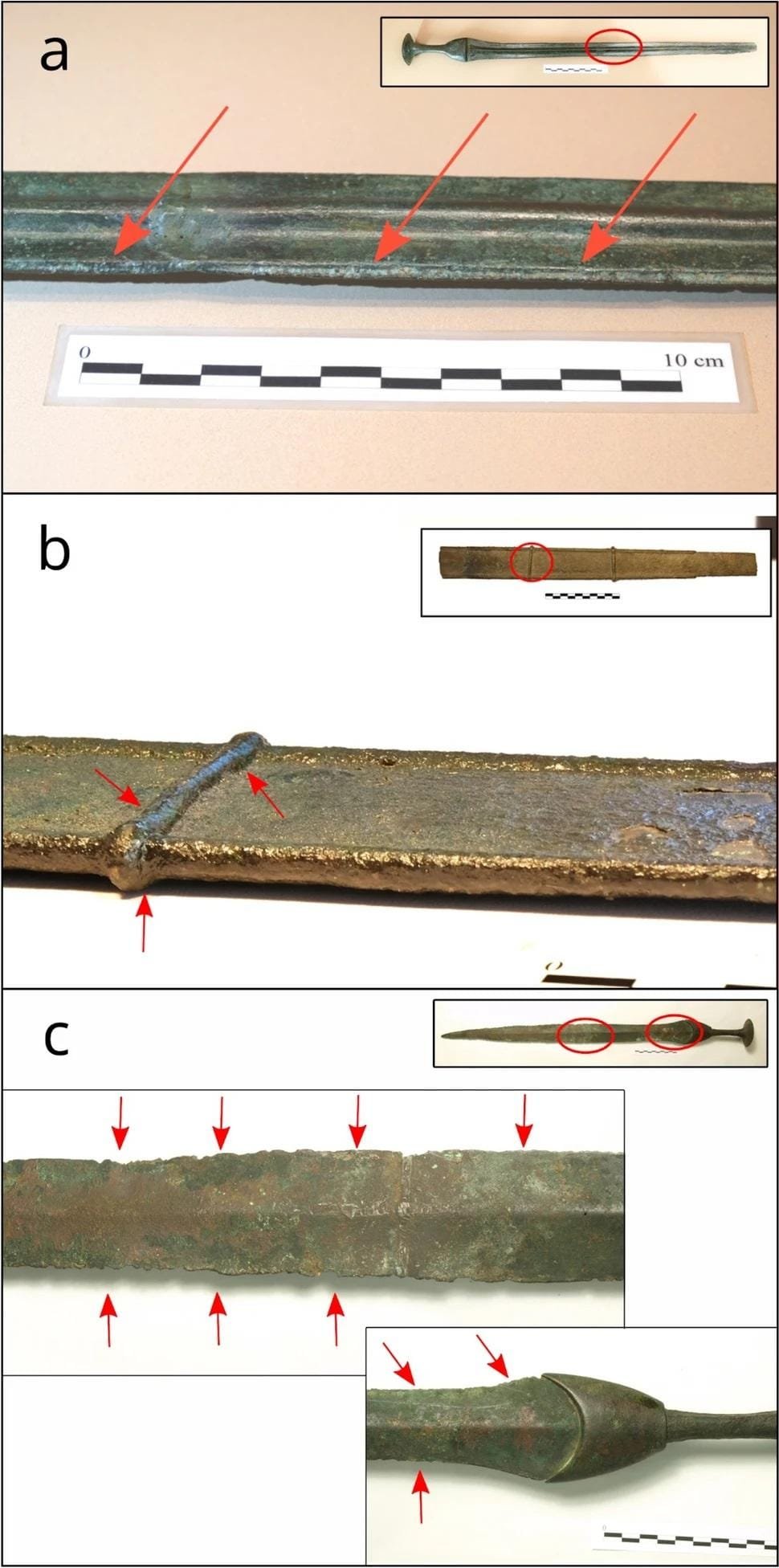

The research team identified 18 Late Bronze Age swords, most classified as the Son Oms type, named after their initial discovery site in Mallorca. These swords exhibit distinctive features, such as solid grips with disc- or diamond-shaped pommels, thin blades with straight edges, and a rhomboidal cross-section with a central rib. They were crafted using advanced methods like lost-wax casting and ternary bronze alloys (copper, tin, and lead).

Chemical analyses revealed notable differences in the alloys used for blades and grips. While blades contained less than 2% lead, grips had significantly higher lead content to improve fluidity during casting. Isotopic studies traced the copper primarily to Linares in mainland Spain, with additional sources in Menorca, Mallorca, and Sardinia. This highlights the complex exchange networks integrating the Balearic Islands into Mediterranean trade routes.

Although the concept of the sword was foreign to the Balearics, these weapons were reimagined in form and function. Unlike their counterparts on the mainland, Balearic swords were not primarily designed for combat. Instead, they served as status symbols and ceremonial objects, reflecting the social and ritual practices of the Talayotic culture.

Key archaeological sites, such as Son Foradat in Sant Llorenç des Cardassar, Es Mitjà Gran, Can Jordi, and Son Matge, have yielded swords in contexts ranging from fortified settlements to burial caves. These discoveries suggest the swords were deeply integrated into the social and symbolic fabric of the islands.

The study emphasizes the concept of “material entanglement,” where foreign materials and technologies were incorporated into local practices, creating hybrid objects. According to the authors, these swords embody a blend of exogenous and indigenous elements. The adoption of foreign techniques like lost-wax casting reflects the exchange of not only materials but also knowledge and skills.

The swords’ biographies reveal a duality: they are products of mainland connections and local reinterpretations.