Archaeologists in Arizona have unearthed a bronze cannon linked to the 16th-century expedition of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, marking the oldest firearm ever found in the continental United States. The cannon, a sand-cast bronze piece measuring 42 inches long and weighing approximately 40 pounds, was discovered at the site of a Spanish stone-and-adobe structure in the Santa Cruz Valley, believed to be part of the short-lived settlement of San Geronimo III.

This find has been detailed in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology, with researchers Deni J. Seymour and William P. Mapoles highlighting its historical significance.

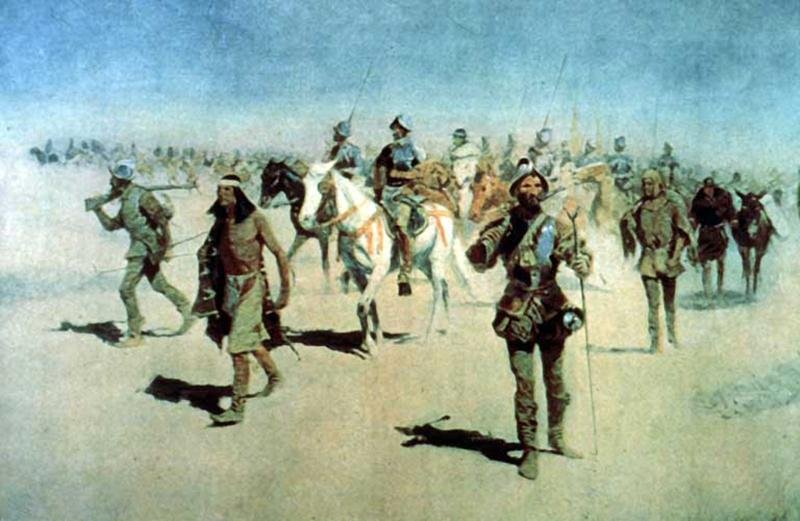

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s 1539–1542 expedition, initiated by Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, aimed to uncover the fabled Seven Cities of Cíbola, legendary metropolises of immense wealth. Coronado led hundreds of soldiers, Indigenous allies, and support personnel northward from Mexico through the American Southwest, reaching as far as Kansas. However, the expedition found no gold-laden cities—only modest Pueblo settlements.

Despite the absence of riches, the expedition left a violent mark on the region, looting Pueblo communities and engaging in the Tiguex War, which caused devastating losses among the Puebloans. The settlement of San Geronimo III, where the cannon was discovered, served as one of Coronado’s temporary bases and was ultimately abandoned after an attack by the local Sobaipuri O’odham people.

The cannon, also referred to as a wall gun, was a versatile piece of artillery used in both defensive and offensive operations. It could breach wooden or adobe walls, projecting lead balls or buckshot with devastating power over a range of up to 700 yards. However, evidence suggests the cannon found in Arizona was never fired; researchers noted the absence of black powder residue.

Radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence techniques placed the cannon firmly within the Coronado era. Additional artifacts at the site, including fragments of European pottery, olive jars, and weapon components, corroborate its connection to the expedition.

The cannon’s plain, unadorned design suggests it was likely cast in the New World, possibly Mexico or the Caribbean, as opposed to Spain, where firearms typically featured ornate decorations. Seymour theorized that the weapon may have been abandoned during the Sobaipuri O’odham attack, which forced the Spanish to retreat.

The Sobaipuri O’odham uprising marked one of the earliest and most consequential Native American revolts against European colonization. As Seymour and Mapoles noted, this resistance delayed Spanish settlement in the region for over 150 years. The cannon’s discovery, alongside other artifacts from the Coronado expedition serves as a reminder of the profound cultural and historical impacts of these encounters.

“This final blow seems to be the precipitating event that led to the abandonment of the wall gun, where it remained snugly encased in an eroded Spanish adobe-and-rock-walled structure for 480 years,” Seymour and her colleagues wrote in their study.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

These so/called explorers were nothin but thieves.

Its not ok to steal another mans stuff by force, thats who they are…common thieves looting people.

“Conquistador your stallion stands in need of company….”

Very interesting…keep it up!

Thank God for Cortez.

The reason for no powder residue was probably due to being properly cleaned

It will be very interesting to get a complete analysis of the archaeology and historical aspects of this find. Up until this time very little (to none) has been found in southern Arizona that is attributable to the Coronado expedition. The Geronimo IIII site is in the Santa Cruz river valley, one river valley west of the San Pedro river valley, the traditional route of the Coronado trail. What did happen in the Santa Cruz valley, and not too many years later, was the expeditions of the Catholic church fathers to establish church activities in the area. The canon is a very significant find, but I suspect this was a sensational attempt to elevate the story by association with the Coronado expedition. Why would they do this? To bring archaeology funds and grants to a specific find so that careers can be supported.

This is interesting. A friend of mine who’s an archaeologist himself told me about it just a little while ago, so I had to look it up for myself. My own town, San Antonio, was founded by Spanish missionaries, so I’ve always found this stuff to be intriguing. Thank’s for article!

About 170 years between the expedition and SA’s founding

Yea sandblasted !

Sandblasted?

I guess from the environment…

it would have been test fired to make sure it could doi it’s job, hopefully with out bursting and then had a proper cleaning to stop corrosion..