Recent research has shed light on the chilling effects of ancient Aztec skull-shaped “death whistles,” instruments known for their eerie, scream-like sounds. Found in graves dating from 1250 to 1521 CE, these clay whistles not only terrified ancient listeners but also provoke a strong psychological and neural response in modern audiences. The study, published in Communications Psychology, is the first to investigate the impact of these sounds on the human brain, offering insights into their historical usage and psychoacoustic properties.

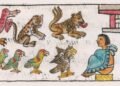

Shaped like human skulls, the whistles produce a high-pitched, piercing sound that mimics a scream, created by the collision of airstreams within the instrument. Numerous examples have been unearthed in Aztec graves, often found alongside the remains of sacrificial victims. Researchers believe they may have served dual purposes: to intimidate enemies on the battlefield and as part of ceremonial rites connected to death and sacrifice.

According to the study, these whistles could symbolize aspects of Aztec mythology. For instance, some experts propose that their shrill sounds represented the razor-sharp winds of Mictlan, the underworld where sacrificial souls were believed to journey. Others suggest they echoed the presence of Ehecatl, the Aztec God of Wind, who, according to legend, created humanity from the bones of the deceased.

The research team, led by cognitive neuroscientists from the University of Zurich, conducted psychoacoustic experiments on European volunteers. Participants were exposed to the death whistle sounds while their brain activity was monitored using neuroimaging techniques. The results revealed heightened activity in the auditory cortex, which processes sound, indicating an immediate state of high alert.

Participants consistently described the sounds as “scary,” “aversive,” and deeply unsettling. According to the researchers, these responses stem from the brain’s difficulty in classifying the sound, which it perceives as having a “hybrid natural-artificial origin.” This ambiguity stimulates both lower-order auditory regions and higher-order cognitive areas responsible for symbolic interpretation, sparking imagination and emotional engagement.

Study authors explained, “Skull whistle sounds attract mental attention by affectively mimicking other aversive and startling sounds produced by nature and technology.” They added that this unique auditory impact likely amplified the emotional intensity of Aztec rituals, particularly those involving human sacrifices.

The research supports theories that death whistles were deliberately used in rituals to elicit fear or reverence. Their ability to confuse and terrify would have been ideal for sacrificial ceremonies and possibly for intimidating enemies during warfare. The whistles’ connection to sacrifice is reinforced by their frequent discovery near sacrificial remains.

The study highlights the Aztecs’ sophisticated use of sound to evoke powerful emotions and spiritual associations. Whether used to terrify foes, honor deities, or mark the transition of souls to the afterlife, these death whistles exemplify the complex interplay between culture, mythology, and human psychology.

By decoding the brain’s reactions to these sounds, the researchers have provided a window into how ancient societies may have harnessed auditory stimuli to influence behavior and emotions. As the study authors concluded, “The whistles’ usage in ritual contexts seems very likely, especially in sacrificial rites and ceremonies related to the dead.”

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

What a fascinating exploration of Aztec death whistles! The connection between sound and psychological impact is so intriguing. It’s eerie to think about how such instruments were used both in rituals and as a means of psychological warfare. I can only imagine the fear they instilled in opponents. Thanks for shedding light on this unique aspect of Aztec culture!

Fascinating post! The concept of the Aztec death whistles is both eerie and intriguing. It’s remarkable how sound can evoke such deep psychological responses, especially in a ritualistic context. I wonder if modern researchers are exploring similar soundscapes for their impact on emotions in contemporary settings.

This post about Aztec death whistles is absolutely fascinating! The concept of sound having such a profound psychological impact in ancient rituals is both eerie and captivating. I can only imagine how terrifying it must have been to hear those whistles during ceremonies. It really makes you think about how sound can shape human experiences and fears. Thank you for sharing such an intriguing piece of history!

This is such a fascinating glimpse into Aztec culture! The psychological implications of the death whistles are mind-blowing. It’s intriguing to think how a sound could evoke fear and influence behavior. I would love to learn more about how these were used in rituals and their effect on the people at the time. Thank you for sharing this unique perspective!