A recent study has revealed a compelling link between Mesopotamian cylinder seals used in trade and the proto-cuneiform symbols that emerged as one of the earliest writing systems. Published in Antiquity, this research, led by Silvia Ferrara from the University of Bologna, has highlighted how engravings on these seals, which date back to around 4400-3400 BCE, influenced the formation of proto-cuneiform signs that appeared between 3350 and 3000 BCE in the ancient city of Uruk, now modern-day Iraq.

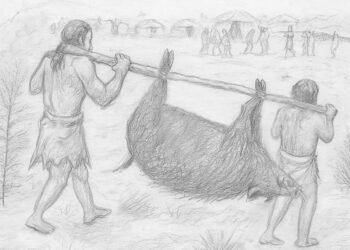

Uruk was among the first major cities, peaking in the 4th millennium BCE with an estimated population of 40,000, whose influence extended from Iran to southeastern Turkey. Its growth coincided with the advent of cylinder seals—small cylindrical objects engraved with motifs that could be rolled across clay to produce symbolic impressions. As Ferrara explains, these seals served as a “non-literate accounting system” in which images on the seals represented commodities like textiles and agricultural goods and were used to record transactions across the region.

Proto-cuneiform emerged in Uruk as a complex writing system with hundreds of pictographic symbols, many of which appear similar to motifs on the cylinder seals. Ferrara, in an interview with the Independent, noted, “The invention of writing marks the transition between prehistory and history, and the findings of this study bridge this divide by illustrating how some late prehistoric images were incorporated into one of the earliest invented writing systems.”

Researchers such as Kathryn Kelley and Mattia Cartolano from the University of Bologna collaborated to examine seal imagery that predated writing but persisted into the proto-literate era. Kelley explained that their study identified specific symbols, like fringed cloth and jars in nets, which appear on both preliterate seals and proto-cuneiform tablets to signify similar concepts, particularly related to trade and transport.

Not all experts are fully convinced of a causal relationship between cylinder seal imagery and proto-cuneiform symbols. Nonetheless, the systematic parallels between seal motifs and proto-cuneiform found in this study provide substantial evidence for a shared visual language that may have evolved into one of the first writing systems.

The findings also hint at the decentralized origins of early writing, suggesting that proto-cuneiform might have been shaped by multiple contributors, including traders and temple administrators, within Uruk’s far-reaching cultural network. Ferrara, in an interview with New Scientist, explained that “People in various roles and locations throughout Mesopotamia—including traders, administrators and leaders—may have made their mark on proto-cuneiform.”

This research marks an important step toward understanding proto-cuneiform, a script that remains partially undeciphered.

Where can I get a cuneiform analyzed in the US.?