Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of an ancient Egyptian practice involving the modification of sheep horns at the mortuary complex of Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt, dating back to approximately 3700 BCE.

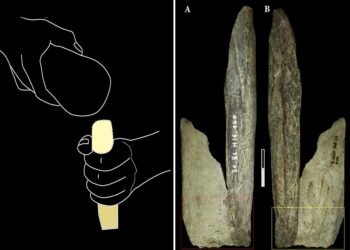

This discovery represents the oldest known case of intentional horn modification in livestock, according to a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. The find comprises six large, castrated male sheep whose skulls displayed deformed horn structures. Unlike naturally grown lateral horns, these sheep had horns that were directed upwards, with some completely removed. The deformations are believed to have been achieved by fracturing and tying the horn bases, an approach that directed the horns to grow in parallel, upright positions.

In describing the findings, Professor Wim Van Neer of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences explained that these modifications were deliberate: “The sheep were deliberately made ‘special’ by castration. In addition, their horns were directed upward, and in one case, the horns were removed.” The discovery of this practice at Hierakonpolis provides the earliest physical evidence of horn modification applied to sheep, a tradition later observed with cattle across various African cultures, including the pastoralist communities of Nubia in the third millennium BCE.

The modification of livestock horns has long been practiced globally to reduce the risk of injury to handlers and animals. Archaeologists found signs of pathological changes on the horn cores of the Hierakonpolis sheep, suggesting a structured and deliberate technique to alter the horns’ growth patterns. Researchers propose that these sheep might have been raised for ceremonial or ritualistic purposes, given that they were discovered in the elite cemetery of the ancient mortuary complex. Further analysis revealed constrictions and fractures on the horn cores and deformities in the skulls, which indicate intentional physical manipulation.

The agrarian society of ancient Egypt relied heavily on domesticated animals for nutritional support, including cattle and sheep, as these provided essential resources such as meat, fat, and dairy. While cattle horn modifications are commonly depicted in Egyptian tomb art dating to the Old Kingdom (circa 2686–2160 BCE), these sheep skulls from Hierakonpolis predate those depictions by nearly a thousand years. The findings suggest that the Egyptians not only utilized sheep and cattle but also engaged in practices to control and manage these animals, contributing to the cultural and symbolic importance of livestock in early Egyptian society.

Iconographic evidence from later periods, including the First Dynasty (circa 3500 BCE) onwards, shows increasing representations of sheep in Egyptian art, as well as their incorporation into the religious system as embodiments of deities, notably ram gods. Hieroglyphic symbols of sheep also emerged, underscoring the animal’s growing significance in Egypt’s socio-religious landscape. By the Middle Kingdom (circa 1991 BCE), depictions in tomb art and archaeological remains, such as those found at Tell el-Dab’a, reflect the symbolic and economic roles of various sheep breeds, including those with back-curving horns like the ammon-type.

The Hierakonpolis study not only expands our understanding of early Egyptian animal husbandry but also illustrates an enduring Nile Valley tradition of livestock modification.

Comments 0