Archaeologists have unearthed an Iron Age burial ground in Pryssgården, southern Sweden, containing at least 50 graves that date back to between 500 BCE and 400 CE.

Among the graves, one stands out due to the unusual placement of a small iron knife, thrust vertically into the earth above the remains of a woman. Researchers at National Historical Museums in Sweden, led by archaeologist Moa Gillberg, believe this gesture was deliberate, but the exact reason remains a mystery.

The cemetery, located about 105 miles southwest of Stockholm, was uncovered in part due to a historical record from 1667 by the Swedish priest Ericus Hemengius. Tasked with cataloging ancient sites within his parish, Hemengius described the burial mounds in Pryssgården and reported seeing what appeared to be fires burning atop these mounds during autumn nights. Archaeologists were initially uncertain if any of these graves survived, or if they lay within the excavation boundaries, but preliminary investigations yielded promising results. Early this year, the team found human bones and artifacts like fibulas, or garment clasps, using metal detectors.

The graves at Pryssgården include both cremation pits and stone-covered graves, a burial style consistent with Iron Age practices in Sweden. One grave contained an especially thick, soot-covered layer of ashes and bone fragments. “When we dug down, we saw that they had put an iron folding knife straight into the ground,” Gillberg explained in a statement, adding, “We don’t know why, but it is clear that it is meant for the woman.” The knife, well-preserved and likely used for tasks such as leatherwork, may have even been on the pyre with the deceased before being driven into the ground. Alongside the knife, a small needle was found, both items suggesting this individual’s societal role or daily activities.

Analysis of the remains in the woman’s grave revealed a toe bone showing signs of osteoarthritis, hinting at the physical toll of her life. Similar graves containing knives and needles have been documented in southern Sweden, such as at the Fiskeby burial ground, where women were also interred with these tools.

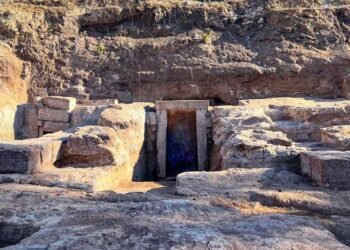

The cemetery itself presents a variety of archaeological features, including an ancient well, remnants of possible dwellings, and a large storehouse. Additionally, a pit initially thought to be a grave was instead revealed to be a significant posthole, indicating that some wooden structure or boundary marker might once have stood there. “One pit turned out to be a fairly large posthole, which might have been part of some form of structure or boundary for the burial ground,” Gillberg said. In another area, an intricate arrangement of stones was found, centered around a large, flat stone, although no bones were present beneath it. According to Gillberg, such stone constructions might have served as memorials or monuments.

Archaeologists are hopeful to learn more about the funerary rituals and the social or symbolic meanings of the grave goods.