A recent study has revealed how emotions were understood and experienced in ancient Mesopotamia. The findings, published in iScience on December 4, were based on an analysis of over one million words of Akkadian texts, written in cuneiform script on clay tablets between 934 and 612 BCE.

Led by Professor Saana Svärd from the University of Helsinki, the multidisciplinary research team included experts from Aalto University, the University of Turku, and Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz. Their work represents the first quantitative analysis linking emotions to body parts in ancient texts. “Even in ancient Mesopotamia, there was a rough understanding of anatomy, for example, the importance of the heart, liver, and lungs,” Svärd explained.

Emotions in the Liver, Heart, and Feet

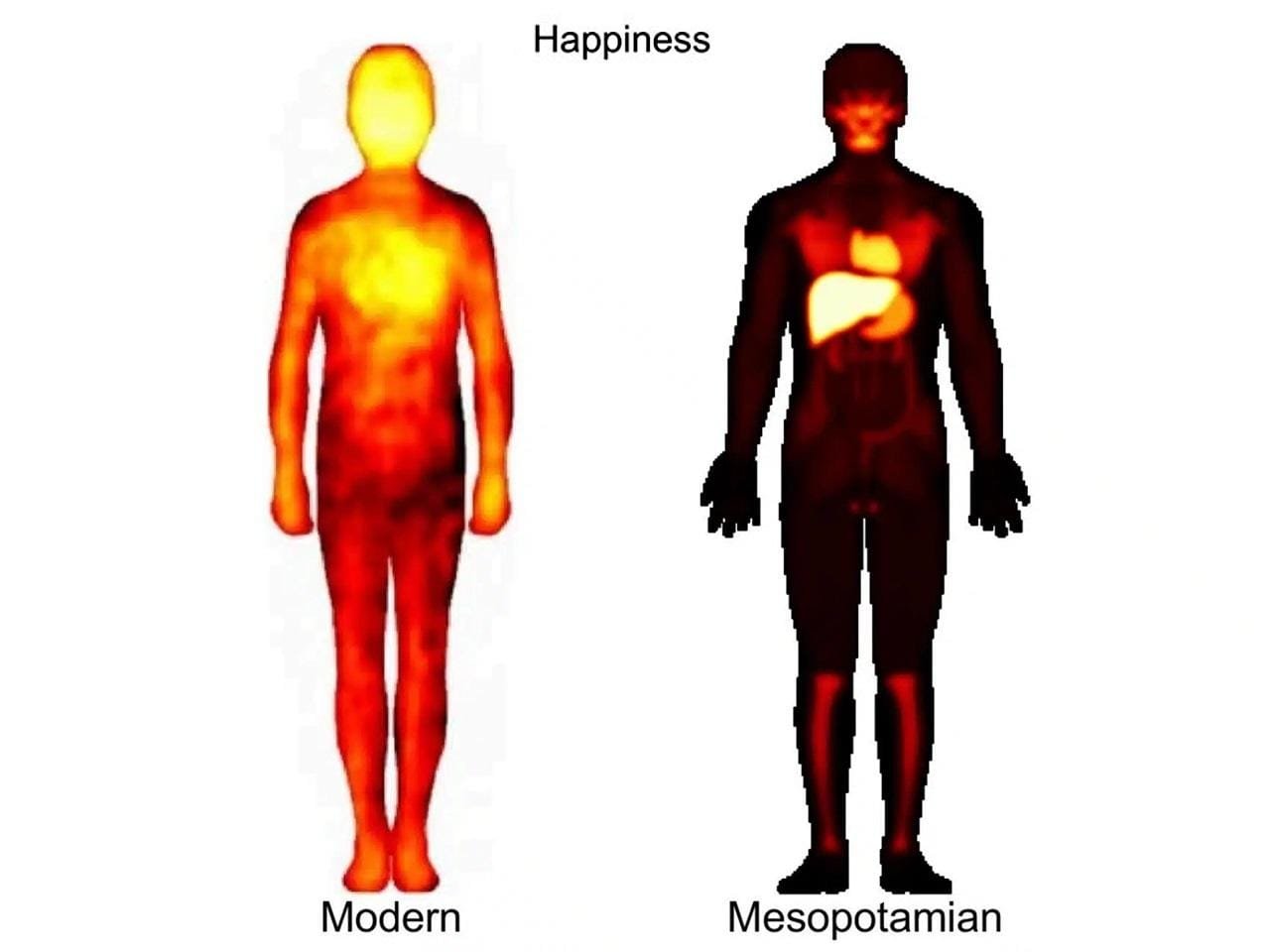

In ancient Mesopotamian texts, happiness was often associated with the liver. Descriptions of joy used terms such as “open,” “shining,” and “full,” highlighting the symbolic and functional importance of the organ. Cognitive neuroscientist Juha Lahnakoski, a visiting researcher at Aalto University, noted the parallels with modern body maps of happiness, except for the unique “glow” in the liver described by Mesopotamians.

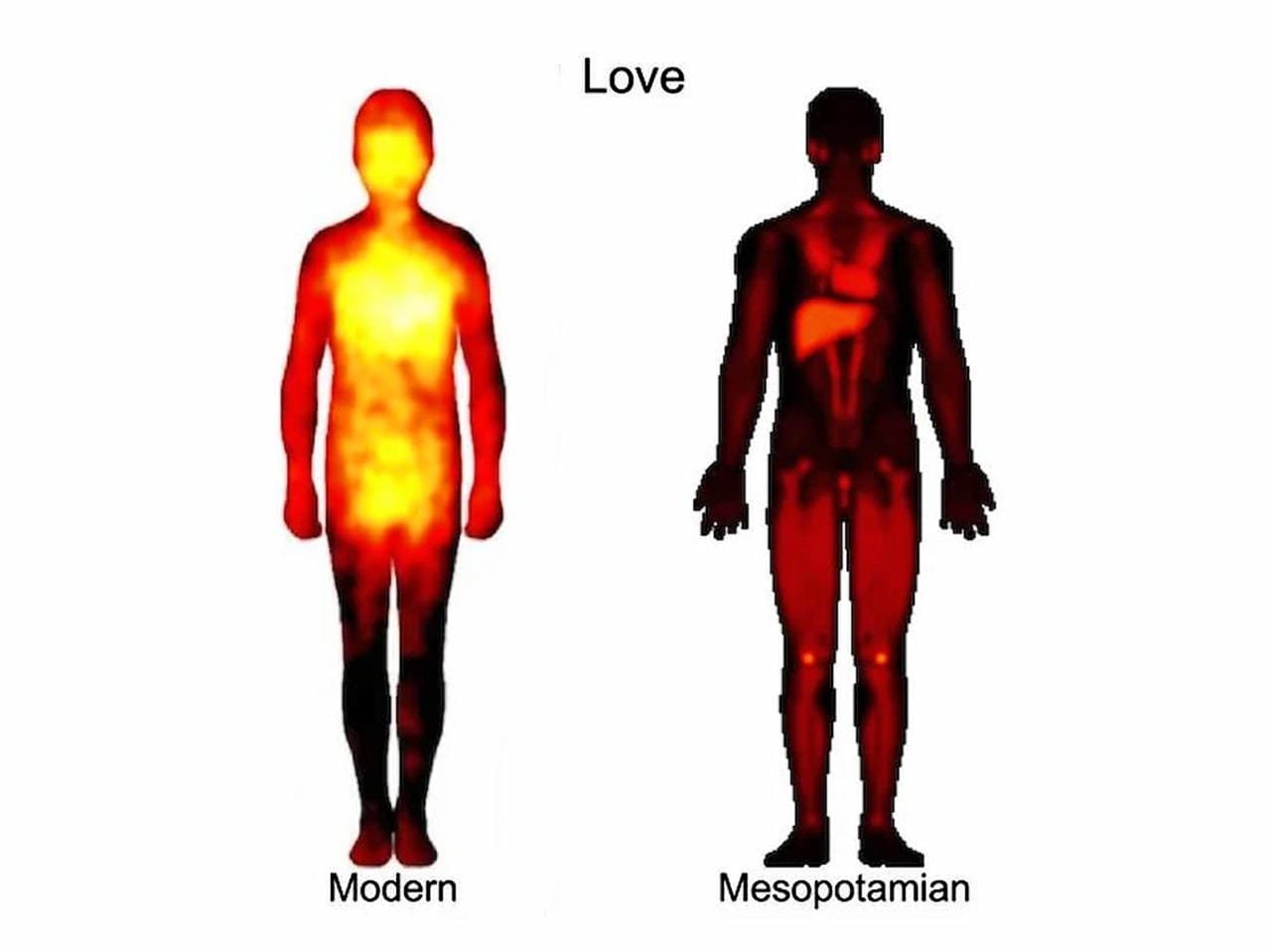

While modern humans often report feeling anger in their upper body and hands, Mesopotamians described anger as concentrated in their feet, using terms like “heated” and “enraged.” Love was another emotion with intriguing differences. Both modern and ancient individuals associate love with the heart, but Mesopotamians also connected it to the liver and knees. This association may reflect the emotional intensity symbolized by bending or bringing someone to their knees.

Methodology and Comparative Analysis

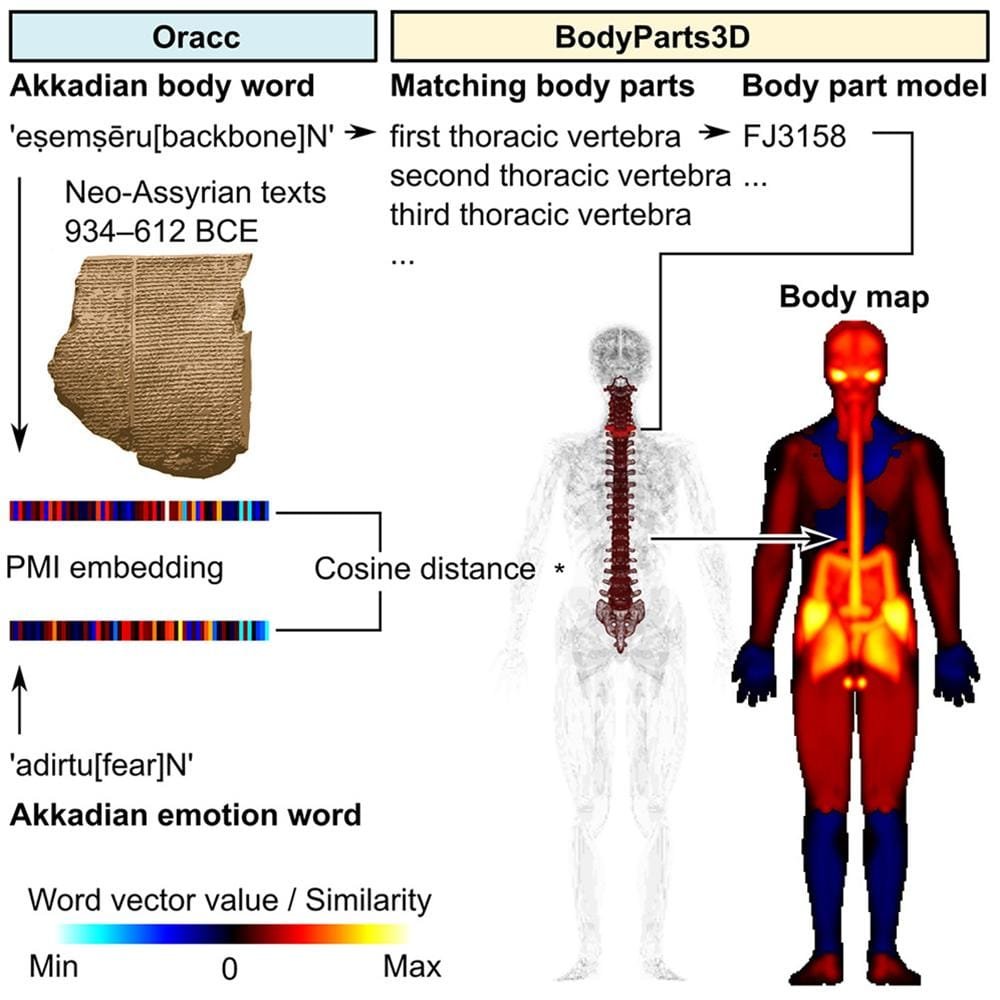

The study employed corpus linguistics, a method developed over years at the Center of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires (ANEE) led by Svärd. This approach enabled researchers to analyze large datasets and map the linguistic descriptions of emotions to specific body parts. The team drew comparisons with modern body maps published a decade ago by Finnish researcher Lauri Nummenmaa and colleagues, which were based on self-reported bodily experiences.

The researchers cautioned against direct comparisons between modern and ancient body maps. “Texts are texts, and emotions are lived and experienced,” Svärd emphasized. The modern maps rely on participants coloring body images based on their feelings, while Mesopotamian maps are inferred from linguistic descriptions in texts produced by scribes, who represented the elite literate class.

Future Research

The study opens new avenues for exploring how emotions are expressed and experienced across different cultures and times. “It could be a useful way to explore intercultural differences in the way we experience emotions,” Svärd noted. The team plans to extend their research to a 20th-century English text corpus containing 100 million words and also analyze Finnish data to further examine emotional expressions.

This research reveals that while some emotions like love have shared physical expressions across millennia, others, such as anger and happiness, differ significantly in their bodily associations. By delving into these ancient texts, scholars not only uncover the emotional lives of the Mesopotamians but also gain insights into the evolving interplay between the mind and body throughout human history.